The Great Resignation is in the rear-view mirror, and the labor market is showing hints of swinging back in the complete opposite direction.

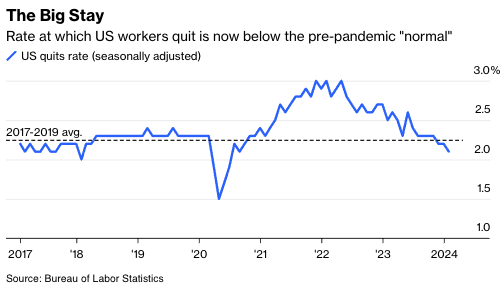

A report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics on Wednesday showed the so-called quits rate—the rate at which workers voluntarily leave their jobs, excluding retirements—fell to 2.1% in January, the lowest since August 2020 on a seasonally adjusted basis. While policymakers have long worried that the labor market had gotten too tight and could fuel inflation, the updated trend in resignations suggests workers are now leaving their jobs less often than was the case before the pandemic disruptions (when inflation was famously low). The Great Resignation has given way to the Big Stay.

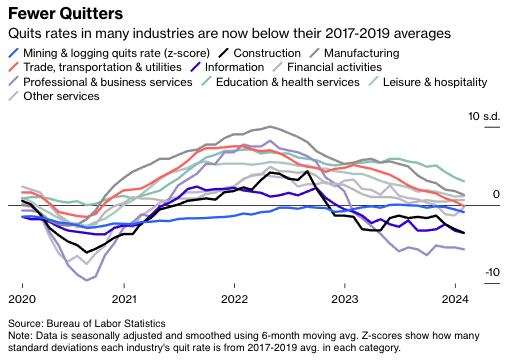

The shift looks fairly broad based, but it’s notably pronounced in some white-collar industries.

The professional and business services supersector (which includes many lawyers, accountants and analysts, among others) has seen a dropoff relative to its 2017-2019 norms. The category’s quits rate stood at around 2.5% in January, down from a pre-pandemic average of 3%. The information industry also stands out as one that’s now seeing even fewer departures than was common before the pandemic (think: reporters, graphic designers, telecommunications workers). Other groups of companies that struggled mightily with excessive departures in 2021 and 2022 (trade and transportation, leisure and hospitality) have essentially seen quitting activity normalize. And a third group is still experiencing excess departures (manufacturing, education and health care.)

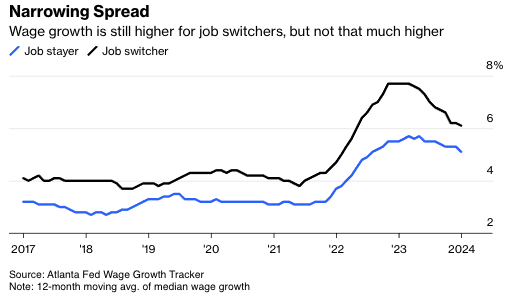

The implications really depend on where we go from here. An optimistic take (from the standpoint of employees) is that U.S. workers are seeing the wage growth they want at their current jobs, so they have no reason to shop around.

The Atlanta Fed’s Wage Growth Tracker suggests that the gap in median wage growth between “job switchers” and “stayers” has been narrowing over the past year. For years after the financial crisis, employers were frustratingly stingy with compensation increases. But it may be the case that the pandemic’s labor shortages have taught employers the value of good employees. As a result, perhaps they’ve been conditioned to offer slightly better raises to prevent attrition even before top-performers show up with competing offer letters in hand. Maybe.

The bearish interpretation suggests that there’s something more insidious happening. Despite superficially strong payroll growth in the U.S., average weekly hours have been declining sharply, and some analysts have begun warning that the labor market may be much weaker than meets the eye. In that context, the drop in quits may be just another sign that the labor market isn’t all sunshine and roses and that, for all the economy’s apparent strength, recession risks haven’t disappeared.

I tend to look for the middle ground. The glory days of job switching and big nominal wage increases are clearly behind us in the U.S., and we may well find that quits will hover slightly below “normal” for a few years. Anyone who was thinking about making a change got their golden opportunity to do so during the pandemic, and—for many of them—that nagging desire to “try something new” may be out of their system.

Meanwhile, the labor market cooldown may be just what policymakers at the Federal Reserve have been looking for.

While no one at the Fed wants to see workers shortchanged, they’ve clearly been worried that overly tight labor markets and too-hot wage growth might keep inflation sticky in certain service industries. The latest data on quits should serve to illustrate that it’s not the risk they once thought it was. That means inflation is likely to keep moderating, and lower borrowing costs—in categories such as mortgages and auto loans—are probably in store over the next year. In that sense, the Big Stay will have some benefits for U.S. households, even if nominal wage increases turn out to be less exciting than they were during the Great Resignation.

Jonathan Levin is a columnist focused on U.S. markets and economics. Previously, he worked as a Bloomberg journalist in the U.S., Brazil and Mexico. He is a CFA charterholder.