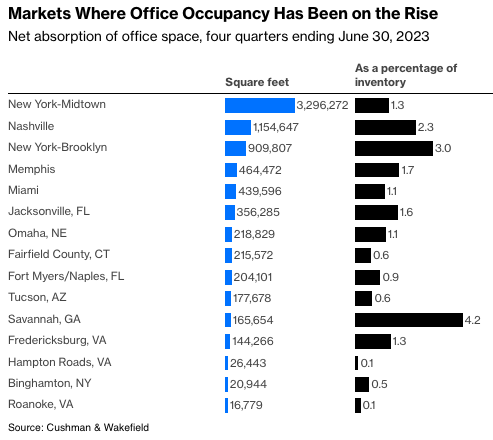

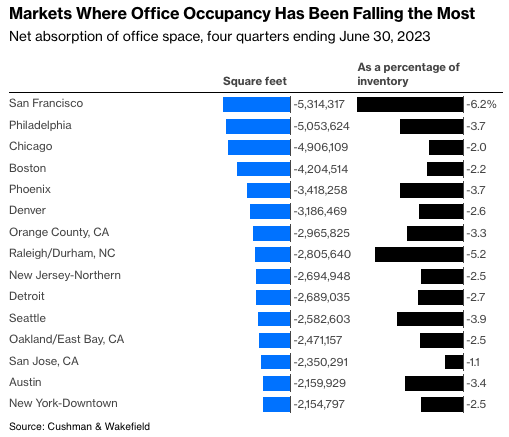

One key metric of the health of a commercial real estate market is net absorption: how many square feet are occupied at the end of a period compared with how many were occupied at the beginning. Not surprisingly, given the rise of remote and hybrid work, net absorption of office space nationwide is currently negative. In the U.S. markets tracked by brokerage firm Cushman & Wakefield, 76.9 million fewer square feet were occupied in the second quarter of this year than in the second quarter of 2022, about 1.4% of office inventory. Only 15 of the 89 markets for which net absorption data is available for the past four quarters put up positive numbers. (For those trying to replicate this at home, Cushman & Wakefield's national Marketbeat report doesn't have Q1 2023 data for Omaha, but the Omaha report does, so I used that data. View in article.)

The U.S. office market with far and away the most net absorption over this period may surprise you. It’s Midtown Manhattan, at 3.3 million square feet. In percentage terms, Midtown came in seventh, behind Brooklyn, Nashville, Jacksonville, Memphis and the very small markets of Savannah, Georgia, and Fredericksburg, Virginia—which is still pretty impressive.

This does not exactly match the apocalyptic tones in which Manhattan commercial real estate is usually discussed these days. “WORTH LESS,” reads the cover of the latest New York magazine. “Manhattan’s office buildings are dangerously empty and crushed by debt, and their owners are in over their heads.” The accompanying article, about RXR Realty’s Scott Rechler, is great, and it’s true that lots of Manhattan office buildings are (1) worth less than they used to be, (2) pretty empty and (3) carrying unsustainable debt loads.

Another key metric of the health of a commercial real estate market is the office vacancy rate, and at 22.4% as of the second quarter, Manhattan’s rate is about twice what it was just before the pandemic and the highest it has been since Cushman & Wakefield started keeping track in 1984. Even the net absorption numbers don’t look too good if you zoom out from just Midtown and just the last four quarters. Negative net absorption in Manhattan’s other two office markets, Downtown and Midtown South, almost exactly canceled out Midtown’s gains over the past year, and in Midtown net absorption since the beginning of 2020 is still negative 17 million square feet.

All in all, then, the gloomy view of the Manhattan office market is not wrong. It’s just that Manhattan’s challenges are far from unique, and it has recently shown signs of life that other cities have not. Its office vacancy rate, for example, isn’t all that far above the national rate of 19.2% and trails not only obvious problem cases San Francisco (27.1%) and Chicago (23.8%) but also Phoenix (26.1%), Houston (25.2%), Austin (25%), Atlanta (23.2%) and Salt Lake City (22.5%). And Midtown Manhattan’s positive net absorption numbers over the past year truly do stand out.

One thing that’s unique about Midtown Manhattan is that it has recently added about 17 million square feet of office space—the equivalent of one Boise, or almost half a Miami—in Hudson Yards, Manhattan West and the Spiral on the far West Side and One Vanderbilt next to Grand Central Terminal. These very new, very tall, very expensive buildings have been filling up with corporate tenants, which serves as an indication of Manhattan’s continuing appeal as a gathering place and status symbol even as it poses big headaches for owners of existing buildings elsewhere in the city. The new buildings have also begun filling city coffers, with City Comptroller Brad Lander noting last month that Hudson Yards was bringing in about $200 million more a year in property taxes than he had expected.

Lander also put out a report last month on the effect on city revenue if office values followed the negative trajectory outlined in the much-discussed “urban doom loop” paper by economists Arun Gupta of New York University and Vrinda Mittal and Stijn van Nieuwenburgh of Columbia University, finding that as of fiscal year 2027 it would knock property tax revenue down 3% relative to the baseline forecast and overall city revenue down 1%. That kind of shortfall would be bad news. It’s just not exactly…apocalyptic.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business, economics and other topics involving charts. A former editor and writer at the Harvard Business Review, Time and Fortune, he is author of The Myth of the Rational Market.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.