Most career paths start on the first day you are out of college, and hopefully the path takes you to the highest levels of recognition, income and prestige. Perhaps you will become a partner (owner) or managing director and reach the finish line of the career track. But consider that most professionals reach the “partner” milestone in their 30s and early 40s, and after that, they might look at the next 30 to 40 remaining years of their career and wonder: “What happens next?”

A lot happens next!

Advisory firms have already done an excellent job developing career tracks for young professionals. But it’s time for them to start thinking about how to steer, manage and motivate those people who have already “made it.” Even the most mature professionals still need a coach and guidance; you can’t just send them out in the world on a quest “to do their own thing.”

Experienced professionals still need goals and ambitions—and to be able to align them with the goals of their organizations, especially if they are co-owners or leaders. Everyone needs goals. And I mean goals, not just a monetary “bait.” Sometimes we think that motivation creates those goals but, in my experience, it’s the other way around. When I train for a marathon, I run 20 to 40 miles a week with enthusiasm while looking forward to race day. But if you ask me to run a little bit each week, I likely will procrastinate.

So if you are going to run a marathon, you need a training plan.

The guidance you give to partners can be tailored to the needs of each person, though some common themes are going to emerge in this “second career track.” I want to explore some of those common themes.

How Many Career Tracks Are There For Partners?

In my experience, there are three career trajectories for people who have reached the level of partner and perhaps acquired company shares or ownership to go with the title:

• Practice builders. These are the partners who create a thriving collection (perhaps a community) of clients and the various levels of professionals and specialists servicing them. They focus on “tending the garden” and continuously improving client service, the depth of relationships and trust. If an advisory firm were a soccer team, this is your midfield. They are versatile players who often have the best technical skills and field vision.

• Brand builders. This is the path for those representing the firm on the outside. They include your writers and public speakers. Your video stars on LinkedIn. They enjoy the public eye and wear the company T-shirt. They build the organization they own rather than their own egos (we are all majority owners of our egos). This is the career path for those who create opportunities, who lead the charge into new markets. They might have their own clients that they serve, but they are also thinking about the broader goals of the entire firm, keeping in mind the marketing and brand-building activities. If a firm were a soccer team, these are your forwards: They are opportunistic and expert at knowing how to position themselves. They just have “the touch.”

• Business builders. These are the partners most interested in running the business, focusing on the strategic and tactical decisions that make it successful. They may not have ever been advisors themselves, may not even have had practices of their own. They may have left clients behind to focus on running business. Their priority as partners is the financial and cultural success of the entire organization. These are your soccer team’s defenders and coaches: They are stable, responsible, staunch; they create the foundation for everything the team does.

Consider that in a firm, just like in a soccer team, all “players” contribute when and where they need to. Forwards go back on defense when needed. Defenders sometimes score goals. In the same way, executives sometimes find themselves in meetings with important clients. Nobody needs to be anchored to one role, but they certainly need to know where they are supposed to be on the field.

Making Choices

I’ve seen people choose the wrong path, either because they don’t know how to find the right one or they were lured to the prestige or income of the wrong one (or at least the one wrong for their talents). Take CEO candidates who openly admit they don’t want to manage people. They just want the title and income. And they don’t see any other path that might get them there, even one they might like more. But all the tracks should be lucrative to those who enjoy them and offer prestige as well.

You should ask new partners to commit to one track for four to five years. And before they commit, you should have a conversation with them about their interests—as well as their abilities. I usually treat with suspicion big statements about a young person’s talents, for example comments such as “Lora is not good at business development.” Firms love to be judgmental about people’s skills, even those with only five or six years of experience who have not had enough time to develop (so we don’t have enough time to judge). I believe Lora can learn and may get better.

But my position changes dramatically when Lora becomes a partner and is no longer in the early stages of her career. In its mature phase, we likely know what Lora is actually good at, and while she can still improve, the rate of improvement will slow down. (If you want to be judgmental, do it with partners who have 12 to 15 years under their belts.)

I believe that advisors should become partners first, before they start specializing in brand- or business-building. I consider those “graduate” activities best suited to those who have mastered being an advisor. A demonstrated aptitude is needed, and I am very skeptical of the approach in which people learn to develop brands or manage teams before they’ve learned how to be advisors and work as team members. That’s a bit like football coaches managing soccer teams (forgive me, Ted Lasso; it was good TV but yours would be a lousy strategy in real life).

The Milestones Of A Partner Career

There are certain things that partners are going to need in terms of motivation to keep them on their long career paths.

They need encouragement to keep growing. If partners don’t have growth goals for any dimension of their work—for instance, the revenue they are responsible for or the knowledge they attain—they may reach a certain level and stop progressing. Harvard professor David Meister says in one of his books that in his experience 70% of partners are “cruisers”—people who follow the path set in their early career, which has now become the path of least resistance. The result is stagnation.

Partners need to keep upgrading their client base. They should, more specifically, seek more complex issues and possibly larger relationships. These partners might have forged emotional connections with their smaller account holders, but smaller or simpler relationships may not challenge them intellectually after a certain point, nor do they reflect the talent and abilities more mature professionals have developed.

Partners must be shown how to build and manage a team. Every firm needs a blueprint for what a team should look like and how it should operate. It doesn’t have to be strict, but partners must come to understand who the teams will involve, when and how and also how to make sure the team is productive while also making sure clients are cared for.

Partners must know how to move client relationships to younger advisors. If we want to build the careers of young professionals, we need to give them clients to work with. So every partner should constantly be asking: “Do I have a team member ready to be the lead?” “Do I have a client who likes my colleague and will enjoy working with them?” “Will this relationship teach my colleague something very valuable and will the client service not suffer?” “Does my colleague specialize in something that this client can benefit from?”

I’ve worked at firms where every partner is encouraged to transition 10% of their clients to a younger advisor each year. This may seem a bit harsh (and perhaps a bit mechanical) but the redirection of accountability is very important.

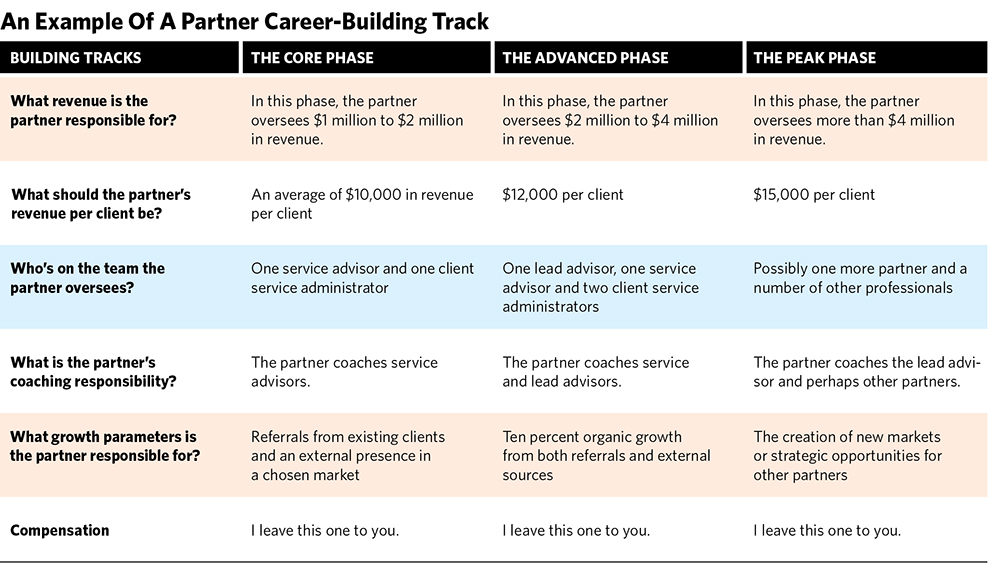

So, what are the milestones in these post-partner career tracks? In the table above I’ve included, I break them out into “core,” “advanced” and “peak” phases.

Though I focused on the “practice builder” track in this instance, you can use a similar grid for the other two.

Who Is Supposed To Do All Of That?

I use a lot of active verbs here—“encourage,” “motivate,” “steer,” “show,” “teach,” “coach,” “pressure.” I do this because guiding partners is more difficult than guiding younger advisors, who are easier to steer because they are curious, eager and malleable and they love to learn. Steering partners is different. I’ve heard it compared to the act of herding.

But there’s no higher priority for a CEO than managing the partners, just as a coach manages starting players.

One approach is to create the position of a “chief practice officer,” someone whose job it is to actually work with the partners. The partners, in turn, work with the rest of the advisory team. This executive can be the accountability partner who sets goals, measures progress and ensures alignment between the ambitions of individuals and their firm. Very few firms use the title “CPO,” but more and more are assigning someone to manage the partner group.

Why Do We Need To Be Managed?

I can already hear the voices asking: “Why do we need to be managed?” Or, “Why do we need to force people to do things they don’t want to do?”

The answer is simple for me. If we are trying to build a team, an organization, then we need to do these dirty deeds—coordinate, manage, organize, motivate and create accountability. If you think of your firm as a recreational soccer team, then sure! Let the kids run around and have some fun. But if we are going to be a professional team and win some games (and trust me, that’s a lot more fun) then we need to find our starters and get organized.

Philip Palaveev is the CEO of the Ensemble Practice LLC. He’s an industry consultant, author of the books G2: Building the Next Generation and The Ensemble Practice and the lead faculty member for the G2 Leadership Institute.