In the corporate-bond market, even a few billion doesn’t get you a seat at the table.

And Najib Nakad is so tired of settling for the scraps left by giants, he hardly bothers to bid for new issues anymore.

“We are too small to have any hope of an allocation,” said Nakad, who helps oversee about 2 billion euros ($2.5 billion) as chief portfolio manager at Hof Hoorneman Bankiers in the picturesque Dutch town of Gouda. “It just goes to the big guys."

Investors like Nakad, 52, who have complained for decades about going up against the bankers that put bond deals together may finally be getting some relief.

Digital disruption, which has changed the face of trading equities, currencies and some government debt, is arriving at one of the last bastions of resistance: the syndicate desk, where corporate bonds are priced and distributed. Selling new issues is a linchpin of investment banks’ profitability. Bond arranging generated about $14 billion for the eight largest banks in the first three quarters of 2017, more than double the haul from equity underwriting, according to data compiled by Bloomberg Intelligence.

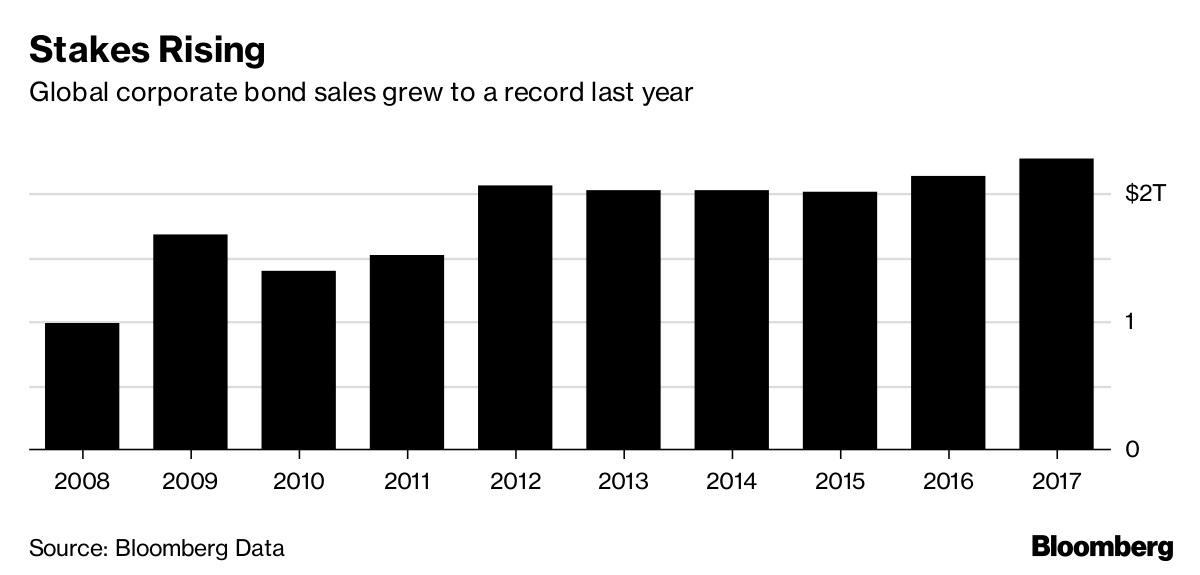

The stakes have soared after a binge that saw companies sell an unprecedented $18 trillion of bonds since 2008, in the aftermath of the crisis that drove benchmark borrowing costs to zero.

Europe is proving particularly fertile ground for digital primary markets because there’s more competition among banks, and electronic trading is more popular than in the U.S. Regulators are paying attention too: Starting this month, syndicate bankers must justify at least the top 20 percent of allocations for regulators under Europe’s revised rulebook known as the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive.

And wherever you are, whether you’re a borrower or a lender, a salesman or a syndicate banker, your world is facing upheaval, with the human factor becoming less significant. Whether it succumbs is another matter, particularly since some of the biggest arrangers have yet to go all in.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because it is. More than a decade ago, at the height of the dot-com boom, the market for initial public offerings was exposed as a den of conflicts and profiteering that was due for change. And while Spotify, owner of the world’s largest paid music service, is planning to go public via a direct listing, the market hasn’t really changed all that much.