Gold is up 25% this year and traded above $1,895 per ounce on Thursday, not far from the 2011 record high of $1,921. Meanwhile, global stocks, as measured by the MSCI World index, have recovered almost all of the losses they suffered as the pandemic ushered the world economy into lockdown, and are within 5% of regaining their February highs.

A look at where the smart money is going, though, suggests one of these rallies may prove unsustainable.

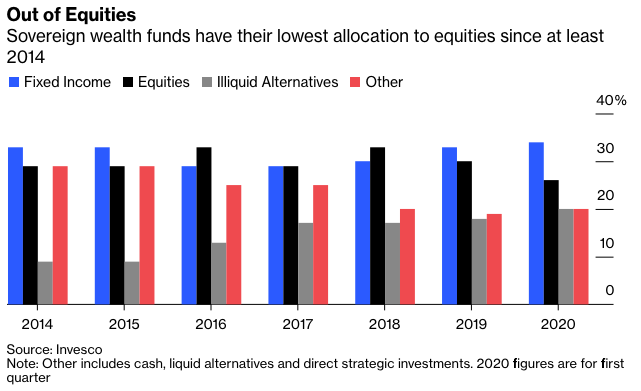

In the first quarter, sovereign funds had reduced their exposure to equities to the lowest level since at least 2014, according to an annual survey published this week by Invesco Ltd. The investment management firm cited “end of cycle concerns that led to decreasing strategic allocations” as the driving force for the diminishing appetite for stocks.

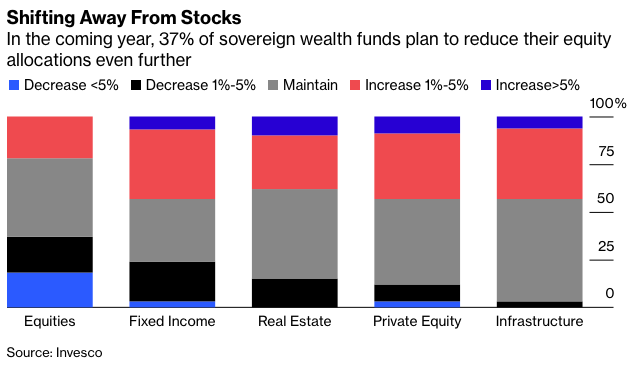

That trend shows no signs of abating. More than a third of wealth funds plan to cut their equity holdings in the coming year, with 18% intending to trim by 5% or more. Private equity and infrastructure are poised to be the key beneficiaries of investment flows, according to Invesco, which surveyed 83 sovereign wealth funds and 56 central banks with total assets of $19 trillion.

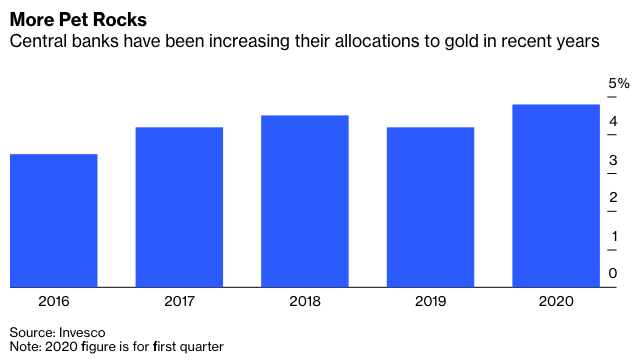

Contrast the mistrust of equities with a rising enthusiasm for gold. Its performance this year has been spectacular. Gold bugs applaud the precious metal as an insurance policy against financial fiddling by monetary authorities that will stoke runaway inflation one of these days; naysayers deride it as nothing better than a pet rock. But central banks have certainly been putting more of their reserves into gold in recent years, the Invesco survey shows.

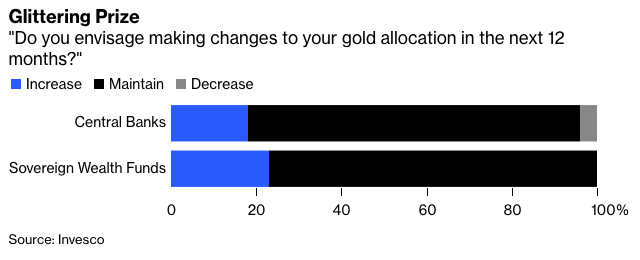

That interest has further to run. Some 18% of central banks plan to increase their gold holdings in the coming year, according to the Invesco report, while 23% of sovereign funds intend to boost their exposure.