The breadth of the stock market is a measure of its health, and the wider the better. So, a narrowing of its focus, as we’ve seen recently, is often a red flag, both for the overall market and the darlings of the moment.

The 10 largest stocks by market capitalization account for 30% of the S&P 500 Index’s total value, and five—Apple Inc., Microsoft Corp., Nvidia Corp., Alphabet Inc. and Tesla Inc.—accounted for about a third of the index’s 27% gain in 2021. In short, if anything goes wrong with that handful of equities, as well as mutual and exchange-traded funds based on the broad market, everyone might be in trouble.

As we all know, trees don’t grow to the sky. Investment firm Dimensional Fund Advisors examined the fate of a stock after it became one of the 10 biggest in the S&P 500. It found that in the decade before joining the club, a stock outperformed the broad market by 10% a year. Nevertheless, investor enthusiasm that pushed a stock into that elite category often pushed it too far, and it lagged behind the broader mark by 1.5% per year over the following decade.

If that’s not worrisome enough, the trailing price-to-earnings ratio of the S&P 500’s top tier in November was 68% higher than their average multiple over the past 25 years, according to JPMorgan Asset Management. And that quarter of a century included the tech-bubble years of the late 1990s.

In most periods of excessive speculation, the lesser lights are the first to fall before the woes spread to the leaders. In the tech arena, fitness equipment company Peloton Interactive Inc. plunged 76% in 2021, online resale platform Poshmark Inc. tumbled 81% and education tech company Chegg Inc. dropped 66%. These and other so-called stay-at-home companies aren’t necessarily headed for bankruptcy, but in 2020 their stock jumped much more than their sales and profits growth could justify.

Sure, many stock investors like to put their money in “One Decision” stocks, as they were called in the early 1970s. These were companies with underlying earnings expected to grow so rapidly and steadily that investors only had to make one decision—to buy them—since they never would need to be sold. But there’s no such thing as a free lunch. One-decision stocks eventually climb to the point where they have only one way to go—down.

Back then, investors focused on what was known as the Nifty Fifty group of stocks. The club, though, shrunk to the point where investors concentrated on hamburger chains (McDonald’s), amusement parks (Disney), gimmick cameras (Polaroid) and motor homes (Winnebago). At the time, I wrote that by constricting their focus to the outward flourishes, investors were anticipating big trouble for the guts of the economy, which they were shunning. As the 1973-1975 recession and bear market unfolded, investors did make a second decision, dumping Polaroid and knocking a zero off the stock’s price as it plunged from $140 a share to $15.

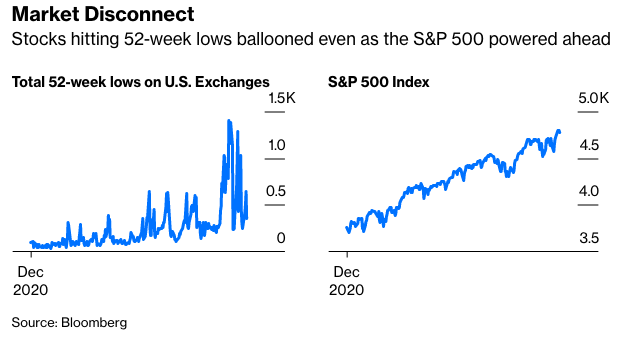

Since 1980, there have been 11 instances in which the market breadth narrowed as sharply as it did between April and October of 2021, according to Goldman Sachs Group Inc. The S&P 500 went on to generate below-average returns over subsequent one-, three-, six- and 12-month intervals most of the time.

Selloffs in growth stocks that would drag down the whole market might well unfold as the Federal Reserve begins to raise interest rates as soon as March. It’s widely believed that the stocks of companies with explosive profits expected in the distant future sell today at the discounted value of those anticipated earnings. So they’re very sensitive to interest rates. Earnings of $1 in 10 years are worth 82 cents today with a 2% discounting rate, but only 61 cents if the discounting rate is 5%.