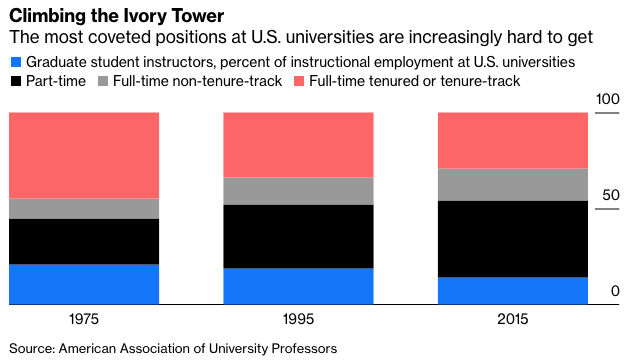

This has happened even as the number of Ph.D.s awarded has risen by more than 50% since 1990. So more smart young people are seeing their dreams of a research career sour into a reality of permanent precarity as adjuncts and lecturers.

This same pattern repeats in the legal profession and in politics, where the size of Congress hasn’t kept up with population growth. Smart, ambitious young people are told to compete ever harder for the plum spots, even as their efforts have a smaller chance of paying off.

The danger is that eventually all the frustrated aspirants decide that the system itself is the problem, and seek to overthrow it. Over-competition is especially dangerous when combined with another factor: slowing growth. A long period of prosperity—such as that from 1985 to 2008—can create high expectations that leave a bitter taste in young people’s mouths when dashed by a slowdown.

How can the U.S. reverse the trend toward elite over-competition? Increasing the number of elite positions is very difficult. Instead, adjust expectations. Taxing inheritances heavily would reduce the number of young people who feel entitled to great wealth. Reducing the number of Ph.D.s would mean fewer disappointed scholars who fail to achieve tenure track. And wealth taxes on the greatest fortunes can lower expectations to more reasonable levels, making people with $10 million feel rich again.

Turchin believes that low inequality helps explain why the unrest of the 1960s and 1970s was ultimately mild and didn’t threaten the integrity of the nation. It’s too late for the U.S. to avoid the current period of turmoil, but by leveling the playing field and changing expectations, it can get an early start on minimizing the next one.

This opinion article was provided by Bloomberg News.

The Wealthy And Privileged Can Revolt, Too

July 6, 2020

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment

Comments

-

Actually, the most intolerant people are those on the left. The usual nonsense from Bloomberg.