Anthony Saglimbene, chief market strategist at Ameriprise Financial Inc., shares this sentiment and suspects that next year’s estimates have stayed too high for too long. Here’s more from him:

The bigger question mark is the 2023 earnings expectations, which I think are still too high if we really are headed for a downturn... Earnings growth typically turns negative during economic downturns or recessions. So, while stock prices have somewhat priced in that environment, analysts have not priced that in in terms of their earnings expectations. And so there’s still a little bit of a disconnect between the macro picture and the economic sentiment for profits and the actual bottom-up analyst estimates for company earnings.

When next year comes and analysts turn out to be too optimistic, which they often are, he added, these estimates will have to come. And if they turn outright negative, that will be a problem.

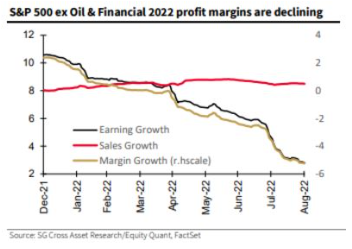

The issue gets trickier when earnings are reduced to their components—revenues and the profit margins extracted from them. Revenue growth has stayed at a constant of about 8% (outside of the energy sector), while margin growth has gone negative, as Lapthorne of SocGen demonstrates in the following chart. Tighter margins can probably be attributed more to rising wages than anything else. But if revenues keep growing like this (and they should, because nominal revenues tend to rise with inflation), it becomes much easier to ride out any squeeze on margins from revitalized union activity:

The issue gets trickier when earnings are reduced to their components—revenues and the profit margins extracted from them. Revenue growth has stayed at a constant of about 8% (outside of the energy sector), while margin growth has gone negative, as Lapthorne of SocGen demonstrates in the following chart. Tighter margins can probably be attributed more to rising wages than anything else. But if revenues keep growing like this (and they should, because nominal revenues tend to rise with inflation), it becomes much easier to ride out any squeeze on margins from revitalized union activity:

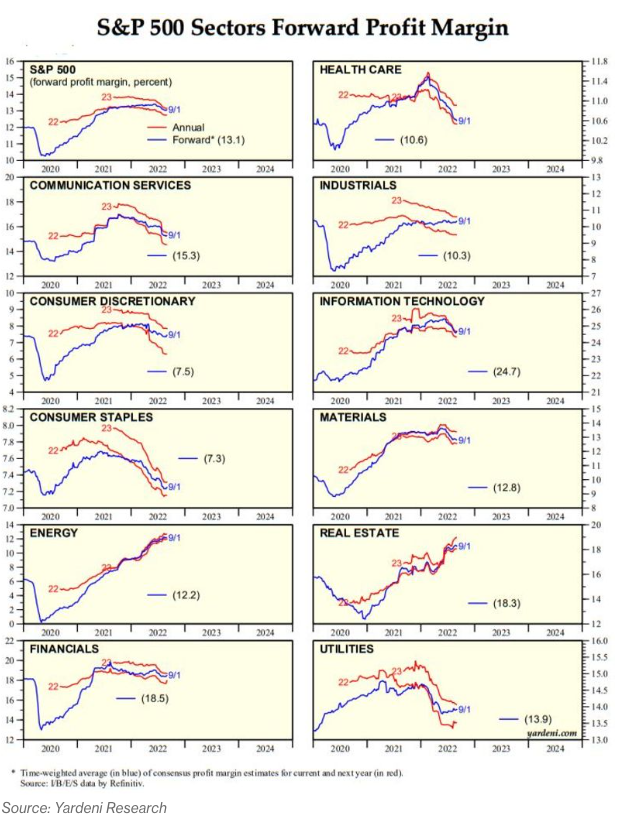

The Street continues to assume that margins are going to tighten a lot. This is seen as happening across all sectors apart from energy and real estate. Yardeni Research Inc. suggests that industry analysts covering the S&P 500 may trim profit margin estimates further until they get another round of guidance from company managements for the third quarter, starting in mid-October. “Analysts remain mostly bullish on S&P 500 revenues in part because they go up along with inflation. Furthermore, very few industries (such as the S&P 500 Homebuilding) are showing signs of falling into a recession currently,” the firm said.

The chart below shows downward revisions in nine of the 11 sectors in the S&P 500, with only energy and real estate margins being adjusted higher. Still, the firm isn’t expecting margin estimates to fall much further this year so long as there’s no economy-wide recession.

Depending on what corporations say next month, and developments in the economy, it’s still possible to construct a moderately bullish case for earnings. Doug Peta, chief U.S. investment strategist at BCA Research, puts it together in two parts. First, the extent of the pandemic-era boost to consumers’ incomes has led consumption to be very resilient. That in turn implies that revenues can keep growing:

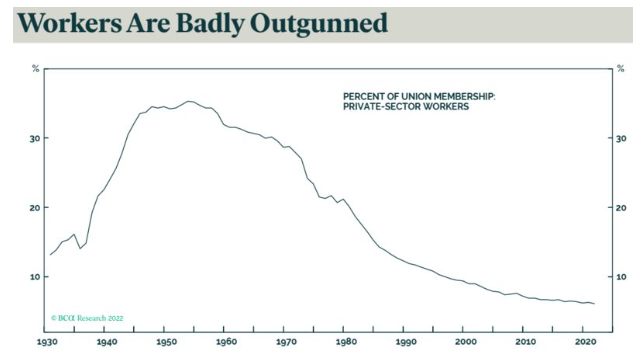

Second, he suggests that the margin squeeze needn’t be as bad as expected because labor’s negotiating power, while strengthening, is doing so from a historically weak position. Labor should be able to extract a bit more from capital, on his argument—but there is a long way to go before unions regain the power they had before President Ronald Reagan took on and defeated the air traffic controllers in 1981:

There’s an economic case, then, that an earnings recession can be avoided. Stronger wage gains or a serious hit to consumption would damage that case. For now, Wall Street analysts are hedging their bets, reducing estimates while still projecting positive growth. As in so many other things, that leaves the stock market highly leveraged to the economy.

John Authers is a senior editor for markets and Bloomberg Opinion columnist. A former chief markets commentator and editor of the Lex column at the Financial Times, he is author of The Fearful Rise of Markets.