Donald Trump’s dark views of a crumbling U.S. economy resonated with an overlooked part of the electorate. Making it great again may prove easier to promise than deliver.

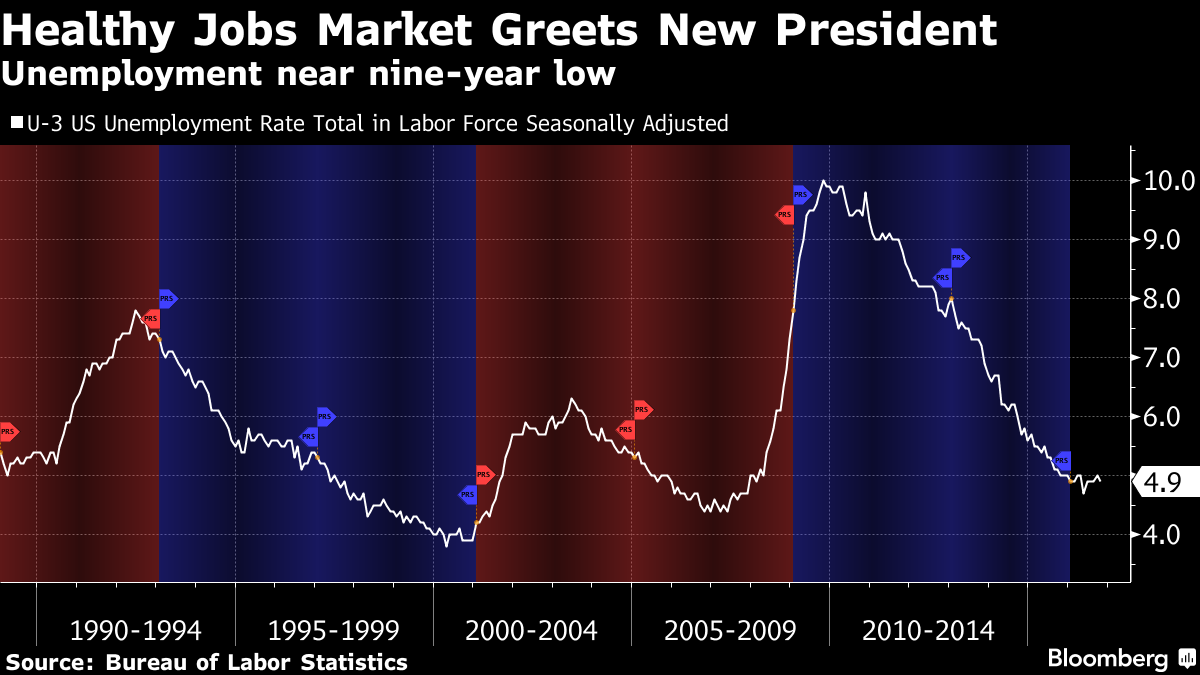

Tapping into pent-up frustration over low wage growth and trade-related job losses, Trump emerged victorious in a tight presidential race with appeals to voters who felt left out of an expansion currently in its eighth year. The Republican’s task now is to steer an economy with clear shortcomings, but one that’s hardly the disaster he characterized during the campaign.

For one, the U.S. economy isn’t showing some of the telltale signs of an impending recession. Inflation and interest rates are low. Consumers aren’t piling up debt, but instead are starting to see wage gains accelerate as the jobs market strengthens. And the housing market, the epicenter of the last economic downturn, is far from being over-built.

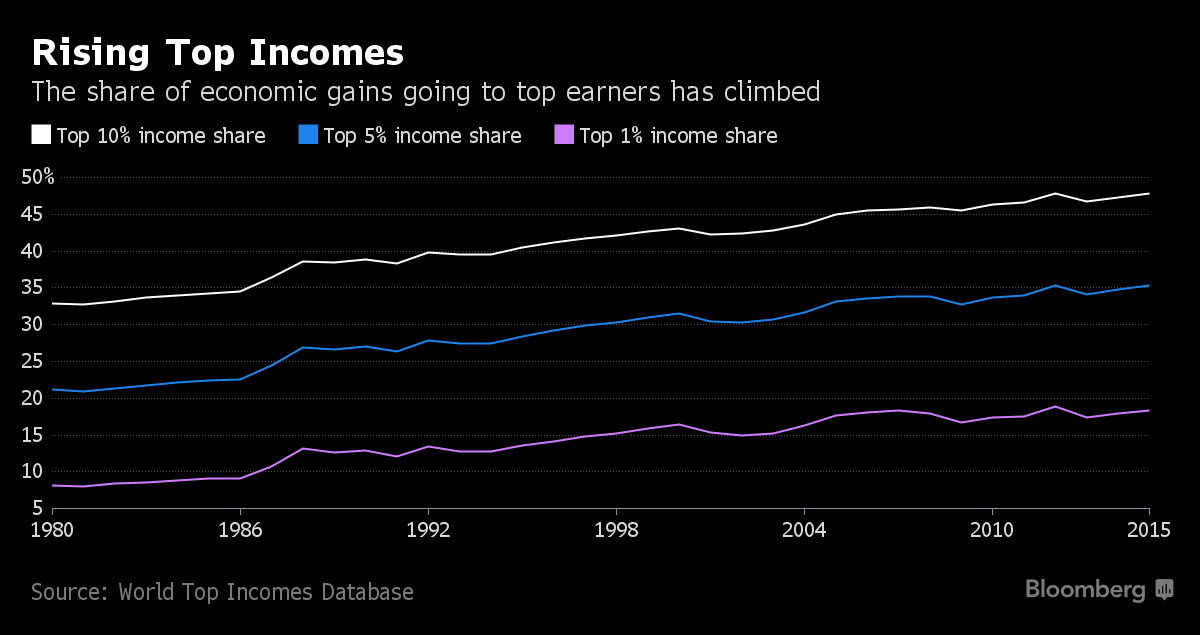

Still, Trump is right that growth has been disappointingly slow and is creating winners and losers. It’s been held back by a slew of what economists call structural problems -- rising income inequality, an aging population and lagging productivity -- that have been years in the making and which helped fuel the widespread voter anger.

“People being upset on the economy matches what’s going on with the uneven recovery,” said Phillip Swagel, a Treasury official during the George W. Bush administration. “There are just so many people being left behind in the economy, and they are voting.”

Middle-class Americans don’t feel well off because they’re being squeezed by the rising cost of health care, child care and college while having to save more for retirement. Trump riled up his base with promises of reformed trade policies that would bring jobs and wealth to America.

Exit polls showed that 52 percent of voters say the economy was the most important issue as they cast their ballots, MSNBC reported Tuesday. Voters were divided on which candidate they think would do a better job handling the economy: 48 percent said Trump, and 46 percent picked his Democratic opponent, Hillary Clinton.

But data show the pain that Americans feel has been building for years. Manufacturing payrolls have posted a long-running decline that started around 1980 and worsened after 2000. Factories have actually added jobs since President Barack Obama took office in 2009, though not enough to reverse the protracted losses that hit communities across the Rust Belt and South especially hard.

What’s more, Trump has argued that growth has been sub-par for years, and the benefits of the expansion haven’t been fairly spread. So far in 2016, GDP has grown 1.7 percent per quarter on average, half the 3.4 percent quarterly growth rate the nation enjoyed during the 1990s.

“You’re seeing a little bit of the urban-rural divide of the winners and losers of globalization, the tendency of metropolitan areas to be the winners, and the rural areas to be the losers,” said Michael Gapen, chief U.S. economist at Barclays Plc in New York. “There is a divide and an income inequality that probably reflect the structural changes in the economy, and that vote is likely showing through.”