You may have read our recent story about a Christian radio talk show host having been indicted for promoting a $194 million currency Ponzi scheme. The travails of the euro and dollar are common knowledge. And for years now, our government has been griping about Chinese manipulation of its currency. All this doesn't make foreign exchange sound like a compelling place to be. However, it is.

Yes, things are murkier now than they were a year or two ago. "The classical correlation among major currencies has broken down," says Christian von Strachwitz, hedge fund manager of the $850 million Quaesta Bond Global Select Strategy, which includes substantial currency management. The leading reasons for this, he explains, are correlation of interest rates, the euro zone and the U.S. bedeviled by massive debt, and the lack of political will to address this issue. There is increasing currency volatility as exchange rates have become hypersensitive to the latest news and data releases rather than fundamentals. "This is leading to shorter-term mispricing, but also to investment opportunities," observes von Strachwitz.

This was no better in evidence then the soaring Swiss franc. U.S. dollar and euzozone investors have been pouring into this safe haven currency as a means escaping their own troubled currencies. A supercharged franc is disastrous for Swiss exports and its economy. In response, the Swiss National Bank stunned the markets in early September by stating it would intervene to whatever degree necessary to prevent the franc from soaring any further than Sf 1.20/euro.The currency had been trading at 1.10 just before the announcement, which instantly resulted in an 8% decline in the franc's value to 1.20. And subsequent flows into safe haven Scandinavian currencies sent the Norwegian krone and Swedish krona rising by more than 2%.

For non-currency experts considering foreign exchange, several key metrics should be followed-growth, government and private sector finance, inflation, interest rates and openness of markets. How these issues trend collectively can help suggest both short- and long-term opportunity.

Take the Australian dollar. It has been a compelling play for years, and uncovering it didn't require arcane forecasting or analysis.

The country has been enjoying 18-plus years of consecutive economic growth. The government's balance sheet and banking system are sound. Inflation is manageable. Business and markets are healthy and transparent.

Besides benefiting from significant commodity production and strong links to Southeast Asian growth, especially China, Australia's significantly higher interest rates are delivering yields no other developed market can match. And it has been doing so for quite some time.

At the beginning of August, the official overnight rate was 4.75%. Since the bottom of the financial crisis, rates have been bumped up 175 basis points by an aggressive Australian central bank. This means AAA-rated short-term sovereign and corporate bonds, along with liquid savings accounts, are paying between 5% and 6%.

These factors have been pushing up the Aussie dollar against the greenback over the past decade. And since the bottom of the financial crisis in early March 2009, after the Aussie drastically sold off to $0.64, it has soared 67% to $1.07 as of September 1. Combine currency appreciation with hefty local interest rates, and U.S. investors who have parked money Down Under are sitting pretty.

Can these positives turn negative? Absolutely. But these are supertanker-scaled forces that take a while to turn. If investors sense a sea change, like Chinese growth materially slowing, they can sell out anytime and wait to see how things play out.

Understanding Currency Markets

The $4 trillion-plus in daily currency trades makes the foreign exchange the largest, most liquid and transparent market in the world. It operates 24/7. And when equity markets collapsed and credit markets seized up during the financial crisis, currency markets functioned well and remained relatively liquid.

What makes currencies so important in an age of paperless transactions?

They remain the oil of the world's economic engines. Trade between sovereign nations is based on the ability to value and exchange currencies. On both a corporate and a government level, currencies are the terms in which budget surpluses and deficits are measured.

While some people don't see currencies as investments, it is a unique asset class that reflects the economic, political, legal and social conditions of a country. When any one of these conditions starts trending away from the norm, the effects usually show up in exchange rates.

Take Norway, a country that stands on its own outside the euro zone. It has one of the highest per capita GDPs of any nation. It boasts high-quality technology and communications infrastructure, is committed to education, and ranks very high in the Economist Intelligence Unit democracy index. Oslo runs a large current account surplus thanks to its strong management of an oil-rich economy, which finances a public retirement trust that diversifies the country's wealth into other assets. All of this has helped push up the value of its currency, the Norwegian krone, over the past decade from 9.26 kroner per dollar to 5.47 kroner.

Because currency is a relative value based on a relationship to another, its worth will change when conditions abroad change.

After it started trading in 1999, the euro collapsed by 25% against the dollar over the ensuing 22 months. The dollar didn't just become supercharged, and European assets didn't suddenly lose their appeal. In fact, at the time, continental stock returns were keeping pace with U.S. equities, in part due to the macroeconomic benefits derived from improving government policies that came directly from the adoption of the euro.

The main drag on the euro was simply uncertainty about the new common currency. Traders played on these fears rather than fundamentals, having manically driven down the euro.

But it didn't stay depressed for long. Exchange rates rapidly reversed course. From the end of 2000, the euro rallied the next eight years, nearly doubling in value against the dollar, generating an annual rate of return of 9%.

The history of the euro-dollar reveals the tendency of currencies to trend for long periods and to overshoot fair valuations. When this happens, it can offer a compelling buying opportunity, betting exchange rates will reverse. But fundamentals must back up the case before one makes such an investment.

The reason mispricing can occur is that the vast majority of currency trades that occur every day don't involve a search for profits but execution of business transactions and government finance. According to Deutsche Bank, 90% of all currency traders are not in it for the money. This means that exchange rates can easily deviate from their fair valuation. The flexibility of the foreign exchange market enables investors to exploit this shift, allowing them to go long or short on virtually all developed market currencies and an increasing number of emerging market currencies.

Going Forward

A sampling of what several currency investors are thinking doesn't clear up the present confusion. The only consensus appears to be that both the euro and dollar are seeing their dominance challenged by currencies of faster-growing, better-managed economies.

Axel Merk, who runs more than $700 million across three of his eponymous currency funds, looks for macroeconomic themes, rather than higher yields, that will push up the value of a currency.

He believes the euro zone, while certainly troubled, is fundamentally sounder than the States-running half the deficit (as a percentage of GDP). Its central bank is not printing money as aggressively as the Fed, and its balance sheet isn't as weighed down with bad assets as the Fed's. Accordingly, Merk is long the euro and short the dollar.

He has been positive about the Swedish krona, especially after the systemic threat posed by Estonia potentially defaulting on huge amounts lent by Swedish banks passed in early 2009. The government started absorbing the excess liquidity it had provided banks (in case Estonia went bust), and the currency rallied from 9.16 Swedish kronor per dollar in March 2009 to below 7.50 by August 2010.

While he likes Australia, Merk thinks New Zealand is an even better play over the near term. In the aftermath of the earthquake that hit New Zealand in February, the central bank substantially cut overnight interest rates to 2.5% to enhance liquidity and investment. At this historical low level, this rate is much less than Australia's, which stands at 4.75%. With the economy recovering, Merk feels interest rates will normalize around 6% to 7%. This move should significantly boost the currency.

The Swiss franc has enjoyed a substantial decade-long run up against the dollar, rising over 25% over the past year and a half alone. Thinking it may have overshot its fair value, Merk has started reducing his exposure to this safe haven currency.

Others think the franc is still a sound currency hedge. Adnan Akant, a managing director and head of foreign exchange at Fischer Francis Trees & Watts, a global asset manager with more than $50 billion in assets, thinks exposure to the franc and the Japanese yen is essential to any currency strategy. He also includes the dollar. "If it didn't stumble when Lehman Brothers failed and U.S. banks were on the brink," he says, "I don't think the debt crisis or a credit downgrade will compromise the dollar's safe-haven status."

Contrary to Merk, Akant is bearish about the euro, expecting it to weaken from $1.40 to $1.30 by year's end, eventually pushing toward $1.20. He has hedged his European exposure through a basket of currencies that include the Canadian and New Zealand dollars, the Swiss franc and the Japanese yen. And for U.S. investors looking to gain from foreign exchange exposure, he would recommend adding the Aussie and Singapore dollars to the mix.

Unlike currency managers who attempt to predict the impact of government policies and corporate behavior, Scott Hixon, head of research and portfolio manager of Invesco's Global Allocation Team, which runs $10 billion, focuses strictly on price trends and interest rate differentials.

The collapse of interest rates across virtually all the developed market is one reason he has significantly pared back his currency investments. Typically 20% of the portfolio, FX now represents only 2%. He is also bothered by the "significant correlation of currencies to equities, preventing the former from offering adequate portfolio diversity, reducing the potential value of taking on additional currency risk." He expects currencies to deliver only modest returns over the next six to 12 months.

Over the past year, Hixon has shorted the dollar against the yen, the Aussie and the New Zealand kiwi. And he's short the euro, the British pound and the Swiss franc versus a basket of Asian and emerging market currencies, including the Brazilian real, the South African rand and the Turkish lira.

Currency Funds

Currency managers typically gain long and short exposure through efficient, leveraged options and forward contracts, as well as through long sovereign positions. While offering a less extensive range of trades, currency funds offer advisors an easier, albeit more expensive, way to gain specific foreign exchange exposure while not expiring like contracts.

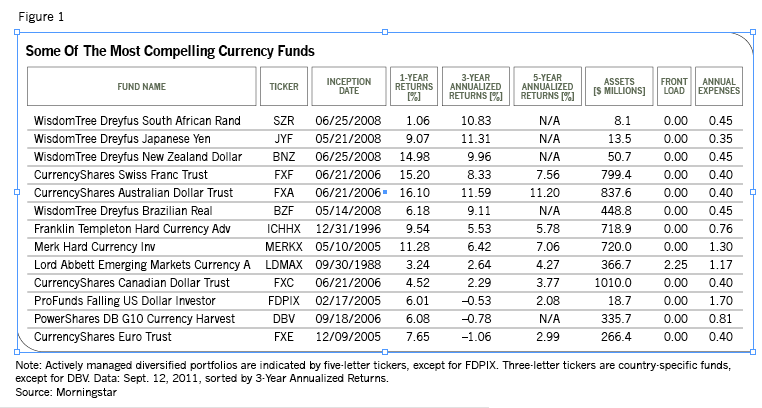

The universe of foreign-exchange funds is rapidly expanding, reflecting the increasing interest in currency exposure. Twelve mutual fund companies are managing assets of nearly $3 billion. Six exchange-traded product providers, with assets over $7 billion, are offering exposure to 15 different currency plays, ranging from the euro, the Japanese yen and the British pound to more exotic investments in the Brazilian real, the Indian rupee, the South African rand and the Chinese yuan.

Part of the appeal of many emerging market currency plays is their delivery of significantly higher overnight rates that investors can collect. The WisdomTree Dreyfus Brazilian Real Fund, for example, is currently paying nearly 8%. A key risk to this play, however, is that a soaring real is leading local monetary authorities to consider taxes and regulations that would inhibit inflows that are chasing yield and driving up the currency.

ETPs are also offering access to specific investment strategies normally achieved by professional FX traders. Rebalanced periodically, the Powershares G10 Currency Harvest fund is a carry trade, investing in the top five yielding currencies and shorting the five lowest-yielding currencies. Barclays offers comparable exposure through iPath-an exchange-traded note. The bank also offers exposure to Asian and Gulf currencies. WisdomTree has two funds that invest in commodity and emerging markets, respectively.

Performance data provided by Morningstar shows there are only a few actively managed mutual fund managers that have delivered consistent gains over the last five years: Franklin Templeton, Lord Abbett and Axel Merk. And save for Australia and Switzerland, few country-specific currency funds have delivered impressive five-year returns (though more than half the specific currency funds have been around for only a few years or less). The cyclical nature of exchange rates makes it difficult to profit over the long run.

However, these funds can play a strategic role in hedging away foreign-exchange risk that comes with foreign investments. They also enable advisors to move opportunistically into a currency that appears ready to rally or fall against the dollar-the latter achieved by shorting the appropriate ETP. But advisors need to be on top of these positions. Profiting in volatile currency markets requires judicious management.