We know that the U.S. economy is currently weak, but the real economy is really weak, and the Federal Reserve’s commitment to precipitate a recession to curb high inflation will make this reality obvious to seemingly oblivious investors.

Real gross domestic product dropped for two consecutive quarters, and although the National Bureau of Economic Research has yet to declare that a recession is underway, those who concentrate on nominal numbers, uncorrected for high inflation, still hope that a business downturn can be avoided. They talk about rising wages in a tight labor market with low unemployment and job openings exceeding the number unemployed. Hourly pay in nominal terms is up 8.8% since May 2021.

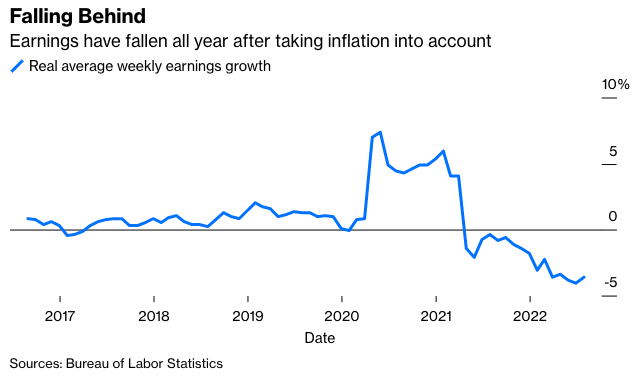

But corrected for inflation, real wages have declined every month since then, bringing the cumulative drop to 3.2%. Even nominal wage growth is slipping, with March’s annual growth rate of 5.6% slowing to 5.2% in July. When other sources of personal income are included — employee benefits, proprietor’s income, rents, interest, dividends and government benefits—and income taxes are subtracted, disposable personal income rose 6.8% in the second quarter from a year earlier but fell 0.6% when adjusted for inflation.

Those who believe consumer spending is robust are confusing the overlays of inflation for the real economy. Since March 2021, nominal retail sales have risen 6.9% but are down 4.1% in real terms.

Denial of the ravages of inflation was also widespread in the late 1960s and 1970s when huge federal spending on the Vietnam War and Great Society programs pushed the economy into double-digit inflation. Despite the Johnson administration’s belief, the economy did not have the supply of labor or the industrial capacity to produce both arsenals of guns (military outlays) and butter (civilian products).

Corporate costs soared as CEOs felt duty-bound to keep employees at least apace of soaring prices. So not only did nominal wages grow but so did real pay. At the same time, depreciation of plant and equipment, based on historic costs, fell far short of the funds needed for replacement. Also, inflation created taxable inventory profits. The dollar value of inventories jumped even though the physical size of stocks didn’t change.

I pleaded with our corporate clients at the time to look at their company results in real terms to see just how much damage inflation inflicted. The universal response was that Wall Street doesn’t care about real results so why should they? And while the Dow Jones Industrial Average, in nominal terms, oscillated around the 1,000 level from the late 1960s to the late 1970s, in real terms it plunged 73.1% from January 1966 to July 1982.

Despite today’s high inflation, some stockholders are also in a state of denial. On Aug. 16, Walmart Inc., the nation’s largest retailer by volume, reported 8.4% revenue growth in the quarter ended July 31 from a year earlier, less than the 8.5% surge in the consumer price index. Grocery sales volume at the retailer dropped during the quarter and operating income fell 6.8% amid higher discounts and selling more thin-margin grocery items. Still, investors bid up Walmart shares 5.1% the day of that announcement.

On August 23, Macy’s Inc., the biggest U.S. department store chain, cut its forecasts for this year due to the economic downturn, the slowdown in consumer spending and markdowns and promotions to get rid of excess inventories. Sales in stores that were open at least a year fell 1.5% in its second quarter from a year earlier. Still, shares of Macy’s closed 3.8% higher that day.