As a retirement economist—not to be confused with a retired economist, which are rare—I often find myself talking to Wall Street types who happen to be in charge of a lot of other people’s money. The conversations vary, but the takeaway almost never does. As a senior executive at a large asset-management firm recently said to me, with surprising candor: “We don’t know how to solve the retirement problem.”

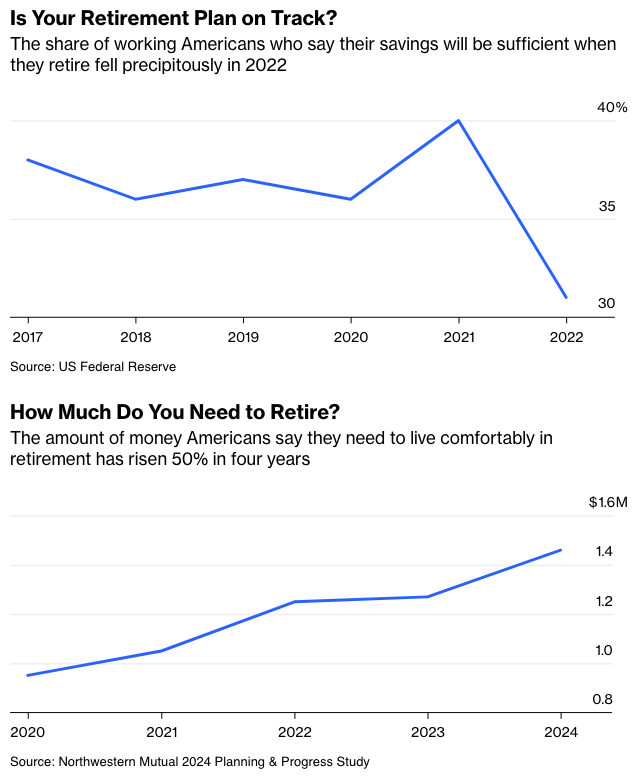

By “problem,” he was referring to the declining share of Americans who view their retirement plans as on track. And by “we,” he was referring to the financial industry—which, to be fair, has made some progress in offering various kinds of accounts and ways of saving. But it is still getting the big things wrong.

People have no idea how much money they need to retire. Their estimate of the costs of retirement increased 50% in the last four years, even though life expectancy barely changed. If anything, they should have revised their estimates down, because higher interest rates mean they need less money to retire. This shows how poorly the financial industry has educated people on what retirement costs and what kind of assets they need.

There is some good news. More employers than ever offer retirement benefits, and automatic enrollment has increased worker participation and improved how investments are made. The 2022 Secure Act should expand coverage even further. Today’s Americans have more money saved than previous generations.

At the same time, Americans are now living longer, and there is no political appetite to encourage people to retire later. That means the number of years Americans are spending in retirement will increase, so they will need more income.

There is no way around the fact: A well-funded retirement free of financial risk is incredibly expensive. Larry Fink, the CEO of BlackRock, points out in his annual shareholder’s letter that the shift to defined-contribution plans such as the 401(k) meant that individuals instead of corporations carried all the risk. This is partially true, though defined-benefit plans had more risk than many of their beneficiaries realized and firms often underestimated the cost of bearing this risk. This is why defined-benefit plans have become so rare in the private sector.

Employers who offered defined-benefit plans did get one thing right, however. They understood the risk problem they faced: providing certain income in retirement.

Defined-contribution pensions don’t have such a clear goal. Often their brochures talk about income, but the strategies appear more geared to achieving a certain level of wealth. Most investors — as well as the retirement industry—judge the success of their retirement portfolio on its value on any given day, or over some arbitrary period, or on how much money it will have on day one of retirement.

But the goal of retirement finance isn’t your wealth level on a particular day. It is predictable income for the length of your retirement. Getting this basic premise wrong burdens retirees with an enormous and intractable risk.

Take the common target-date fund, which invests young savers in stocks and moves them into bonds (whose duration shrinks) as they age. This strategy aims to grow their money and keep their assets from falling too much in value as they approach and enter retirement. But it does nothing to help them know how much to spend each year, let alone how to maintain that level of spending. The current most popular spending rules leave retirees with huge yearly swings in income and vulnerable to the risk of running out of money.

Solutions do exist. They begin by redefining the retirement problem as one of future income, not current wealth. That means different benchmarks that treat retirement accounts like mini defined-benefit plans and assess how close clients are to reaching an income stream years from now.

What might these benchmarks look like? They would involve converting asset balance into income by using a longer-term interest rate. The original Secure Act requires that retirement account statements show an income estimate, but it is often secondary to the display of the asset balance. How well a saver is doing, and whether the plan has offered suitable investments, is still benchmarked to a wealth goal.

Income, as a goal, should be more prominent from the start—and it should be how success is primarily measured. The investment menu should also offer more income-oriented investment strategies. The idea is to give people a sense from the beginning of how much income they can expect when they retire. It would help ease the transition from working and saving to retirement and spending.

There also need to be more and better annuities, both immediate and deferred. It is impossible for people to predict how long they will live and what their care needs will be. The best way to manage that risk is through insurance. Through the magic of risk-pooling, people who need care or will live to be 105 are subsidized by people who don’t or won’t. Everyone gets more certainty, and it is cheaper than bearing that risk individually.

People fear annuities for good reasons. They have gotten a bad reputation both because the low-rate environment made them very expensive, and there are also many expensive products with hidden risks and features people don’t need. People also don’t like giving up their hard-earned savings to an insurance company.

Finally, America needs to start thinking more creatively about work. One reason the conversation around increasing the retirement age has become so politically toxic is that too many people see working as a binary: You’re either working full time or not at all. This makes no sense. The U.S. can find ways to subsidize people who physically can’t work in their 60s and still strongly encourage everyone else to work longer. It may be part-time work, which many people can do into their 70s. Staying partially engaged in the labor force is incredibly valuable both financially and mentally.

But proposing solutions, I have learned, is the easy part. Making actual changes is just about impossible. Risk aversion and bad incentives are so embedded in the retirement industry that excavating them would take a whole other column.

To give just one example: Even changing what a statement shows is hard. Record keepers, who have the tedious and harder-than-it-should-be task of keeping track of what’s in everyone’s accounts each month, have no desire or incentive to change how anything is measured. And they are very powerful.

In my conversations with people on Wall Street, I often say that I love being a retirement economist because it offers both satisfaction and security. It’s satisfying because figuring out how to make retirement work better for more people isn’t actually that complicated. And it’s secure because, while there is always an audience for ideas on “how to solve the retirement problem,” no one has much of an incentive to act on them.

Allison Schrager is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering economics. A senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, she is author of An Economist Walks Into a Brothel: And Other Unexpected Places to Understand Risk.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.