Sunlight bounced off Goldman Sachs Group Inc.’s glass-and-steel Manhattan headquarters on a warm August morning in 2013. Eyes locked on their screens, traders and engineers shifted in their seats as exchanges prepared to open.

Unbeknownst to anyone, the machines were about to revolt.

Bam. Bam. Bam. Dummy trade signals that were supposed to stay within the company’s electronic systems broke loose and slammed into computers at the New York Stock Exchange’s options markets. So many orders crashed through that by 8:44 a.m., safeguards within Goldman Sachs sprang into action, severing the connection between the company and the exchanges.

It took ages for anyone to notice the anomaly. At 9:01 a.m. an employee finally saw the blockage and lifted it. A river of mispriced orders surged through the restored connection. Minutes later, the volume triggered another stoppage. And another. And another.

By the time the trades were blocked for the last time, less than an hour after they began, Goldman Sachs executed orders to sell more than 1.5 million options contracts for $1. The cause? A coder had mistakenly programmed a router to send placeholder bids as live orders. If not for the good graces of the options exchanges, the bank would have lost $500 million, according to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. Cancellations and price adjustments reduced that to $38 million.

The blunder, in one corner of the stock market, exposed a soft spot in the controls and technology at the company’s larger equities business. Despite being the dominant equities shop on Wall Street, its electronic operations had become almost an afterthought. Goldman Sachs had gotten to the top by catering to the types of companies that ruled financial markets for decades: long-short hedge funds and active asset managers. In the pre-crisis era, Goldman’s human traders made billions of dollars in profit and became the envy of their peers by using the company’s balance sheet to take risks.

But as one of the greatest bull markets in history took off, professional stockpickers struggled to generate adequate returns. Volatility vanished as central banks placated markets. Trillions of dollars moved from active strategies into index and exchange-traded funds, favoring electronic platforms, where commissions are a fraction of voice trading. Quantitative hedge funds such as Renaissance Technologies and Two Sigma Investments hoovered up assets while their old-school peers withered.

The 149-year-old investment bank wasn’t alone in being slow to anticipate the seismic shift in equities. But as excuses go, Goldman Sachs had a couple of good ones. Senior executives worried about cracks beginning to form in the market’s foundations. And for more than a decade, Wall Street’s bond traders enjoyed unrivaled prosperity, buoyed by the expansion of new markets for derivatives and a decline in interest rates that made it more lucrative to simply hold investments.

Few benefited more from this than Goldman Sachs, which became the most profitable company in Wall Street history under former commodities salesman Lloyd Blankfein, who may step down as chief executive officer as early as this year. Using house money to facilitate bond trades—or principal risk-taking—was far more lucrative than merely acting on clients’ behalf to execute stock orders. In 2009, Goldman traders reaped $33 billion in revenue, two-thirds of it from fixed income.

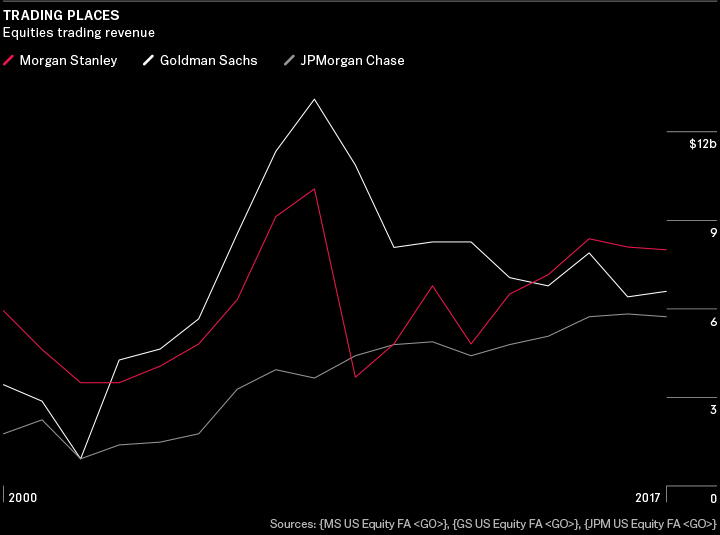

But constraints brought about by the financial crisis ended the leverage that had fueled the boom. Fixed-income traders felt the brunt of the changes, and in the years since, equities traders —especially those with a technology background—have enjoyed a renaissance. Their rise has touched off a battle for supremacy that’s come down to only three companies: Goldman Sachs, Morgan Stanley, and JPMorgan Chase. These rivals are now locked in a technological arms race to control a $58 billion-a-year industry. As they each jockey for an edge over the other, no one who trades on Wall Street is safe.