Dear Larry Kudlow,

It looks like you are our last hope for preventing the tariff tantrum with China from escalating into a full-blown trade war.

Larry, a few years ago we had a conversation about China when we both spoke at an investment conference. Following on that, I'd urge you to use your knowledge and access to the president to help him understand the economic and political risks of launching a trade war with our country's largest trading partner.

Given your experience at Bear Stearns and the New York Fed, I'm sure you've spent many hours trying to help President Trump understand that trade is not a zero-sum game, that the deficit is not a scorecard for trade, and that unemployment has actually been lower during periods when our trade deficit has been higher relative to GDP.

But I also understand, from my own government service, how difficult it can be to help a political boss understand complex issues, especially when long-held convictions collide with facts.

So, today I'd like to resume our conversation with some ideas for persuading Trump to redirect his strategy to focus on achieving the world's best trade deal with President Xi Jinping.

Trump's busy schedule means you won't have a lot of time to make your case, so I'd like to help with a summary of the key issues to raise with him.

Our Economy Is Strong, So We Don't Need A Trade War

As the president recently tweeted, “The Economy is soooo good, perhaps the best in our country's history. . .” While that isn't entirely accurate, I get the point: business is booming, unemployment is low and the stock market is up. America is great!

I know the president is focused on manufacturing. That too is already great. The Fed's industrial production index fell during the last recession, but recovered to reach an all-time high in November 2014, without new taxes on Chinese imports. The index has continued to edge up.

The manufacturing share of total employment, as you know, peaked back in the 1950s, long before we imported anything from China, as our manufacturers became more efficient. We are making a record amount of stuff with far fewer people. The average American steelworker produced 1,100 tons in 2000, for example, up from 260 tons per worker in 1960.

The manufacturing share of employment also has fallen because as consumers become wealthier, they spend more on services than on goods.

Many American Firms Are Winning In China

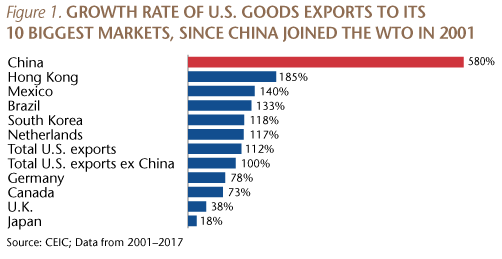

China's 2001 inclusion in the World Trade Organization (WTO) has been a boon to many American companies. From then until 2017, U.S. exports to China rose by 580 percent, while our exports to the rest of the world were up by only 100 percent. This has opened up opportunities for many publicly listed American companies. General Motors sold more than 4 million vehicles in China last year, marking the sixth consecutive year in which China was a larger retail market than the United States for GM. China contributes 18 percent of Apple's revenue in the third quarter of 2018. Nike shoe sales in China rose 31 percent YoY during the most recent quarter, and accounted for about 16 percent of its global shoe revenue. China contributes roughly 15 percent of global earnings for firms such as Nvidia, Dolby and Tesla.

You've probably read that imports from China led to 2.4 million U.S. job losses. But those jobs were lost over a more than 10-year period. Another study found that U.S. exports to China directly and indirectly supported 1.8 million new jobs in just one year, 2015.

While some American companies are blocked from the Chinese market, many are very profitable there. The American Chamber of Commerce in Shanghai represents 1,500 companies, and their latest member survey found that over three-quarters of U.S. firms in China were profitable last year, the same share as in 2016. Nearly 58 percent of companies reported higher revenue growth in China than globally.

It is worth noting that the value, in dollar terms, of retail spending in China was equal to 90 percent of U.S. retail spending last year, up from 27 percent a decade ago. Within a few years, consumer spending in China will be greater than that in the United States. We don't want to start a trade war that will lead Beijing to retaliate by shutting American companies out of that market.

A Trade War With China Will Inflict Serious Pain On American Workers, Farmers, Families And Businesses

Trade with China and other countries has helped American families stretch their budgets. The consumer price index for personal computers, for example, declined 96 percent between 1997 and 2015. Because a tariff on imports is effectively a tax on American consumers who buy those goods, if the administration expands the scope of the tariffs to cover all imports from China, the prices of everything from mobile phones (80 percent of imports came from China last year) and laptops (93 percent) to Christmas ornaments (94 percent) and toys (88 percent) will rise, probably erasing the impact of the president's tax cut.

Some workers will also suffer. Let's take Boeing as an example. The company is America's largest exporter, and China is its largest market. The company expects China's domestic and international air travel to grow at an average annual rate of 7.6 percent over the next 20 years. Boeing employs more than 50,000 factory workers and 45,000 engineers across all 50 states, and supports an additional 1.3 million supplier-related jobs in the U.S. Some of those jobs would be at risk if China responds to a trade war by instructing its airlines to buy more from Airbus and less from Boeing.

Apple, which says it is the largest U.S. corporate taxpayer, is another example. Although most of its products undergo final assembly in China, the company said, in a recent letter to the administration, “Every Apple product contains parts or materials from the United States and . . . reflects the labor of 2 million U.S. workers across all 50 states.”

China is our largest overseas market for agricultural goods. About one-third of the U.S. soybean crop is sold to China, which could cut its purchases and buy more from Brazil and Argentina. (It is worth noting that 24 Republican members of Congress represent districts that account for about 60 percent of the total U.S. soybean crop.)

The global supply chain is critical to small firms that manufacture goods in the United States, and China is a key supplier. A prolonged trade war would accelerate the dispersal of the supply chain from China to other Asian countries, but is very unlikely to result in production and assembly of those goods moving to the United States. New taxes on those components will instead lead to a mix of lower margins and higher final goods prices in the United States, as well as layoffs.