The New York Community Trust established the first DAF-like charitable account in 1931, but the funds weren’t heavily promoted until investment firms such as Fidelity, Schwab, and Vanguard won IRS permission in the 1990s to set up charities that would offer the accounts.

The move presented an opportunity to collect fees. More than half of Fidelity Charitable’s $50 billion in assets sat in Fidelity products in June 2021, the latest audited financial statements show. Those investments would generate about $90 million in management fees annually based on current fund expenses. That’s on top of administrative fees that start at 0.6% of assets a year and decline for larger accounts. Fidelity Charitable says those costs were far lower than for “virtually any other method of grant-making” except writing a check.

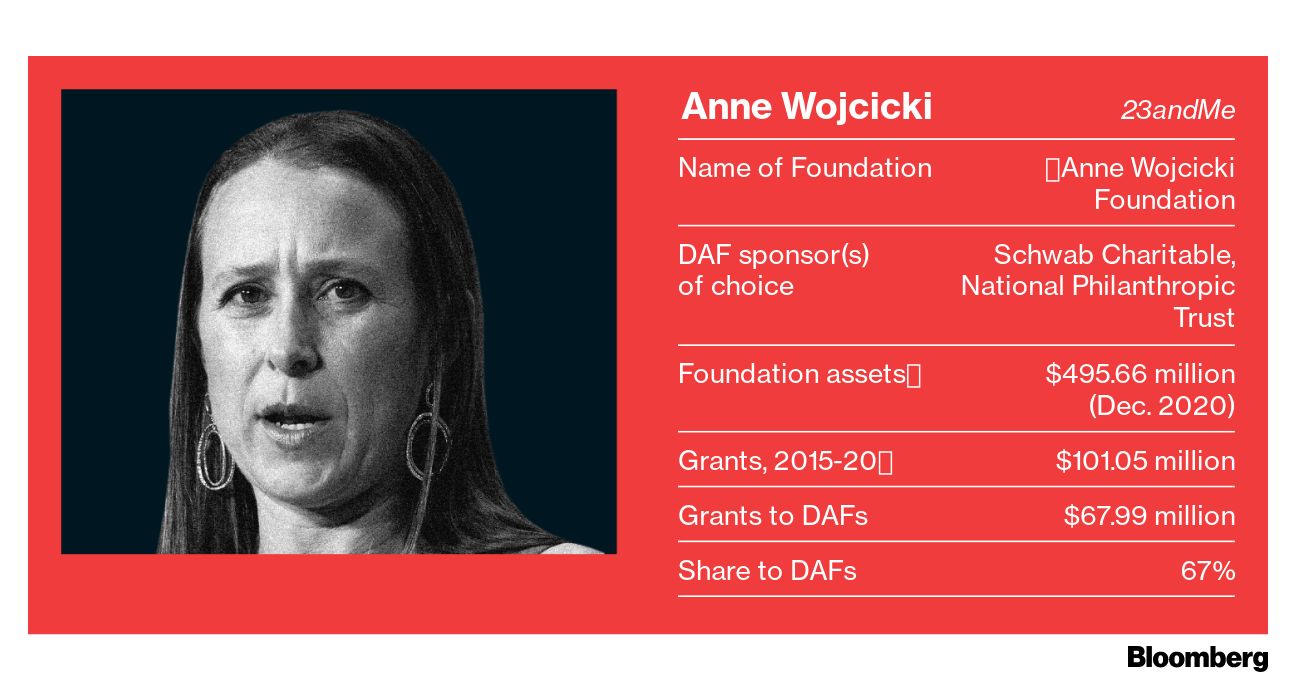

As the accounts became more popular, Wall Street companies including Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and Morgan Stanley set up their own nonprofits to sponsor the funds. It didn’t hurt that financial advisers, who often continue managing the charitable dollars after they move to the accounts, pitched the benefits: Donors could have control over the timing of disbursements. The accounts also simplified the administrative burden of philanthropy, so much so that many wealthy people liquidated private foundations and put the money into them. Privacy has also been a big draw. Individuals can make anonymous gifts; foundations can’t.

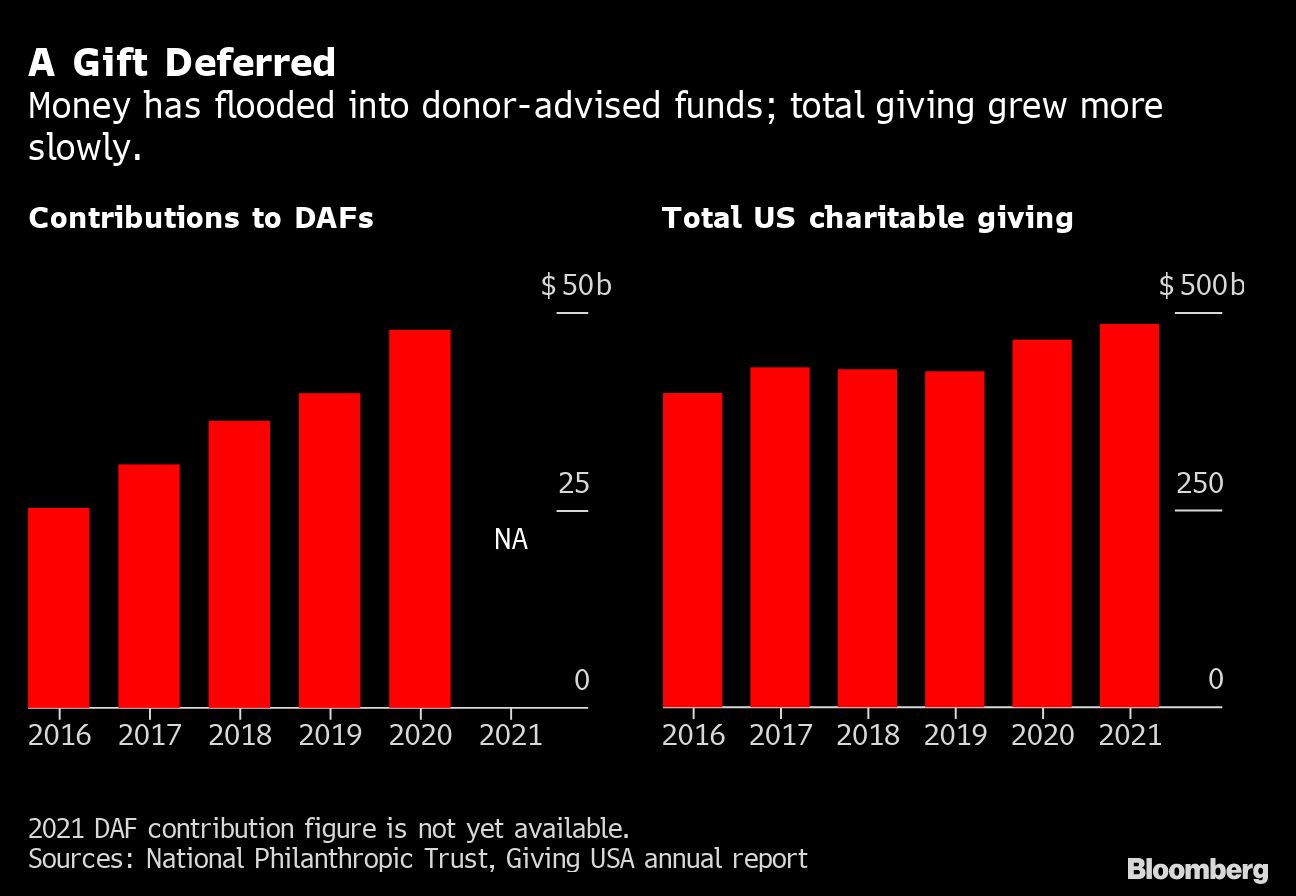

As the wealth of billionaires soared during the Covid-19 pandemic, controversy intensified over charitable rules. Calls for bigger and bolder giving came from prominent individuals and institutions, urging the wealthy to voluntarily unlock money in their donor-advised funds and foundations. A coalition of philanthropy experts, major foundations, and billionaires including former hedge fund trader John Arnold, Galaxy Digital Holding’s Michael Novogratz, and Baupost Group’s Seth Klarman pressed for new rules to accelerate giving.

Charities, though, mostly stayed quiet. “There’s a lot of feeling that when people get the tax deduction, it should be put to work,” says Jan Masaoka, CEO of the California Association of Nonprofits, which lobbies on behalf of almost 10,000 charitable organizations. But “nonprofits never want to do anything that would be offensive at all to a donor or foundation. There is not a more emotional issue among our members than DAFs, and we’re able to say something about it and they’re not.”

Especially galling to those pushing for change is that much of the money flowing into charitable vehicles in effect comes from public coffers. In 2022, US taxpayers will hand those earning more than $1 million almost $30 billion in charitable incentives, according to the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation. Donors collect billions more from state and local tax breaks.

Last year, for example, Musk faced what he claimed would be the biggest tax bill in US history after exercising millions of options on Tesla shares. In November, filings show the world’s richest person gave $5.7 billion of the electric-car maker’s stock to charity. With the top federal tax rate at 37%, the gift could cut Musk’s 2021 federal tax bill by as much as 37¢ for every dollar given away. By contributing shares, rather than selling the stock for cash, he could also avoid taxes on capital gains, saving an additional 20¢. Minimizing the US estate tax, a 40% levy on large fortunes at death, brings his total theoretical savings to 74% of his gift.