Twitter had a brief freakout last week after White House spokesman Sean Spicer seemed to suggest that pretax 401(k) contributions to retirement savings were in danger. The White House hastened to say that wasn’t part of the proposed tax overhaul it’s trying to move through Congress.

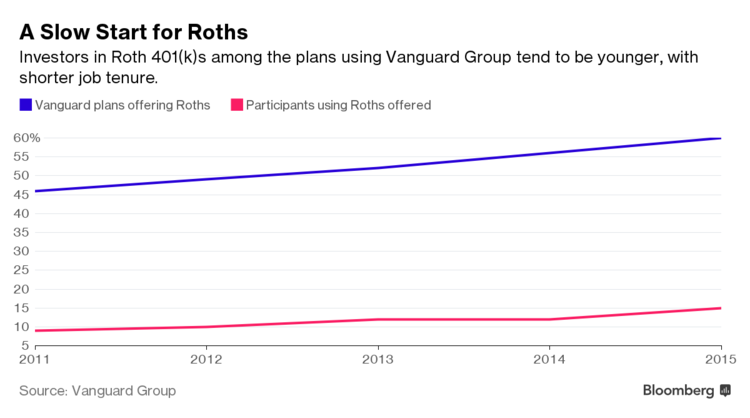

But Washington, and the money management industry, are abuzz with rumors. Will Roth 401(k)s and Roth Individual Retirement Accounts, which are funded with after-tax money, take on a greater role, even a starring role, in our retirement planning? If so, what will that mean for our finances later in life? The prospect of an upheaval is making a lot of employers who offer retirement plans—and, no doubt, a lot of aspiring retirees—nervous.

Here’s the situation and some of the likely outcomes.

To pass permanent legislation with a simple majority (in today's Senate, that means without Democrats on board), it must be revenue-neutral, so President Donald Trump needs to find new revenue to offset the cuts he’s seeking. Employers who offer their workers a defined-contribution, or 401(k), plan, or a similar option, fear that Trump and Congress will take a whack at the pretax status of those 401(k) contributions as part of the tax legislation they’re pursuing.

Traditional 401(k)s and IRAs held about $15 trillion in assets ($7 trillion and $7.9 trillion, respectively) as of the fourth quarter of 2016, according to the Investment Company Institute. The government gets its taxes on that money only once people start drawing down their accounts, after maybe 30 or 40 years of saving. Congress, on the other hand, typically thinks in terms of just 10 years when it crafts a budget.

You can see the problem—and, for the government, the opportunity to capture that revenue earlier. The $1,544,000,000,000 red bar below is for employer-sponsored defined-contribution and defined-benefit retirement plans.

From 2016 to 2020, pretax money going into defined-contribution plans was forecast to reduce federal revenue by an estimated $583.6 billion, according to the nonpartisan congressional Joint Committee on Taxation. If you tally the tax breaks for all kinds of retirement savings plans, the ballpark figure is $1.5 trillion in revenue left on the table over a decade, “and that makes it very tempting to take from,” said Bradford Campbell, a partner at law firm Drinker Biddle and a former assistant secretary of labor for employee benefits and former head of the Employee Benefits Security Administration.

Even before last week’s confusion, White House National Economic Council Director Gary Cohn was reported to have discussed “ideas that would remove pretax benefits from retirement accounts including 401(k)s and shift them to after-tax benefits” in a meeting with the Senate Banking Committee in April.

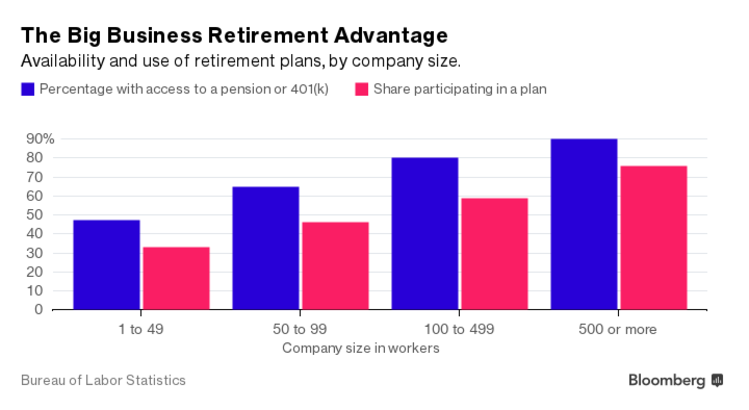

Large plan employers worry that a bigger role for Roths in the retirement plans they offer might not appeal as much to savers as the immediate tax break they get from a traditional 401(k) or IRA. They’re concerned that plan participation and contribution levels will decline and that their 401(k) will become a less attractive benefit.

For small-business owners, who don’t have the muscle to negotiate administrative costs down and who may rely heavily on their own 401(k), changes to the retirement savings law could discourage them from offering a plan. For example, if income levels are used to determine who can contribute pretax, or if the pretax contribution limit is reduced (since the average employee doesn’t contribute the full amount), that could be a disincentive.