The U.S. also allows donors a deduction limit of 30% of adjusted gross U.S. income and the excess can be carried forward for five years. Switzerland’s limit is only 20%, and there’s no deduction for the excess. In the U.S., England and Switzerland, meanwhile, a donor can get tax breaks for donating publicly traded securities, something not allowed in Hong Kong, which allows deductions only for cash (Hong Kong, however, may offer stamp duty relief on transfers of stock and, in any event, capital gains may not be taxable in Hong Kong, which has a relatively benign territorial system of tax).

England’s system, with its so-called “gift aid” and “share aid,” offers tax advantages for donors similar to those in the U.S., but only for contributions of cash, publicly listed securities and real property (more on this below). There is no tax advantage for contributions of other assets. By comparison, the U.S. allows a deduction for most appreciated assets other than publicly traded securities in an amount equal to the donor’s tax basis in the asset.

When it comes to contributions of real estate, Switzerland provides a deduction based on the market value of the property; England does the same, but only if the real estate is located in the U.K. The U.S. limits the deduction to the donor’s basis for a gift to a private foundation. As noted before, Hong Kong provides no deduction for non-cash contributions.

The U.S., England and Switzerland (at the canton level) have an inheritance tax against which bequests to charity are deductible or exempt. Hong Kong has no inheritance tax, so there’s no tax advantage in avoiding the territory. In fact, its relatively low tax rates mean that most charitable giving done there is not primarily motivated by tax relief.

Of the four jurisdictions, only the United States allows tax relief for charitable contributions accomplished via split-interest trusts that provide a financial return to the donor or the donor’s family.

But if tax relief is the main issue, it’s only relevant if the donor has taxable income in the country in which the foundation is qualified, or an estate that will be subject to inheritance tax in that country. Thus, the donor who has income and assets only in the various countries of Europe will generally not find tax relief with a grant-making charity in the United States or Asia. Moreover, because a charity formed in another country will most likely not be qualified in the donor’s home country, a gift to that charity may trigger a tax charge under the home country’s gift or inheritance tax, as is the case in England. This trap may also catch the unwary donor who contributes to overseas operating charities. Where charitable tax relief is immaterial to a donor, the choice of jurisdiction is considerably widened, and certain “offshore” jurisdictions may be attractive to those seeking a light-touch regulatory regime.

One useful strategy is to create a “dual-qualified” structure. In such a case, a charity formed in the United States creates a subsidiary in Hong Kong or the U.K. and structures the subsidiary so that it will qualify as a charity in those countries yet be treated as part of the U.S. charity for U.S. tax law. This structure is particularly beneficial where a donor is subject to tax in both the U.S. and England or in both the U.S. and Hong Kong, since it gives the donor income tax benefits in two countries.

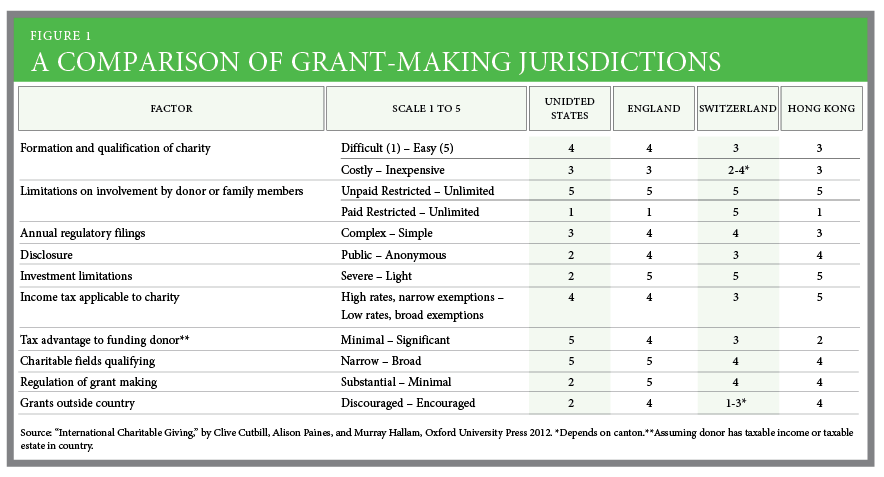

In the end, picking the right jurisdiction is more like judging a figure skating competition than doing your arithmetic homework; my number rankings should not obscure the fact that the final choice is more art than number crunching. Reasonable minds may disagree about the country factor rankings—nor will two philanthropic individuals agree on what factors are relevant to them, and they will certainly weigh the factors differently. Clearly, consultation with expert legal counsel is essential.