Our Research

In this article, we try to correct some of those assumptions. We have used Monte Carlo simulations to estimate sustainable spending rates for retirements beginning in January 2015, and we draw elements from previously published research articles.

We take into account fees for both financial advice and fund management while also incorporating the heightened sequence of returns risk facing retirees in the current low-yield world and the reality that 30 years is increasingly not a conservative planning horizon.

As a preview of the findings, we estimated that a 40% stock allocation and a 30-year planning horizon would support a 2.1% sustainable initial spending rate, provided one is willing to accept a 10% chance of failure (with a volatile investment portfolio, there is no such thing as a guaranteed spending rate). There are also very few investors who would accept a 10% chance of outliving their money.

If we extend the horizon to 40 years, with the same asset allocation and acceptable failure probability, the sustainable spending rate drops even further, to 1.49%.

So it’s clear to us that after incorporating fees and today’s sequence-of-return risk, the 4% rule of thumb has a very low chance of success. Even a 2% withdrawal has a 10% chance of failure.

This research will be revised annually to incorporate changes in stocks’ and bonds’ current valuations. Though the withdrawal rates are low today, they wouldn’t have been at other times. They would have been much higher, for example, for an investor starting retirement on January 1, 1982.

Our Limited Historical Experience

It is a fallacy to conclude that just because the 4% rule worked in the U.S. historical data, it can be expected to continue to work just as well for today’s retirees. During the past 145 years, America grew at an unprecedented rate and became the world’s economic superpower. Other developed markets experienced lower growth. The 4% rule has not worked nearly as well in most other developed market countries, for which we have sufficient financial market data to create such a test. While it seems reasonable to focus on U.S. historical data, a century of slower growth will mean lower returns for future retirees.

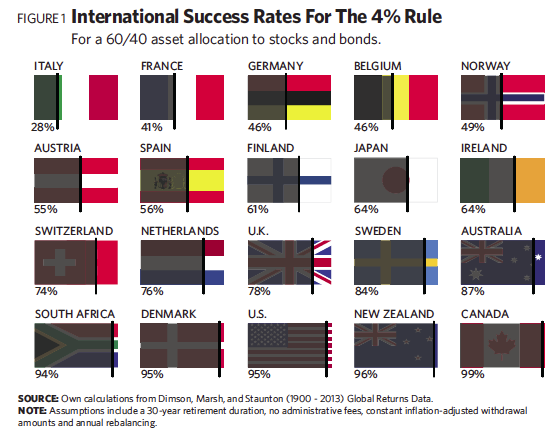

Figure 1 summarizes the international experience on the topic of “safe withdrawal rates.” The table provides historical success rates for the 4% rule using financial market data for 20 countries since 1900.

Results can vary when we use different data sets and asset allocations. In this case, with a fixed allocation of 60% stocks and 40% bonds, the 4% rule worked in 95% of the rolling historical periods in the U.S. Success rates were also over 90% for the local stock and bond data in Canada, Denmark, New Zealand and South Africa. In the other 15 countries, results varied dramatically. The historical success rates for the 4% rule were as low as 28% for Italy, 41% for France and 46% for Belgium and Germany. If the U.S. has lower GDP growth in the coming century than it did in the last century, our success rate would also be much lower.

Why 4% Could Fail

September 1, 2015

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment

Comments

-

Interesting perspective. I'm wondering if the authors can provide a little more detail on methods used to compute joint life expectant from the Society of Actuaries data. I haven't been able to locate the exact data set used in this study, but I have found and used the 2000 data set from the Society of Actuaries via the Vanguard Life Expectancy Calculator (https://personal.vanguard.com/us/insights/retirement/plan-for-a-long-retirement-tool). Joint life expectancy until age 95 for a 65 year old couple is 18% under this calculator...I can't find the data set used to support a 31% probability cited in the study. The SOA has a calculator using the Social Security mortality rates via 2010 which pegs the probability of the couple living until 95 at 14% (https://www.soa.org/research/software-tools/research-simple-life-calculator.aspx). I'm just seeking to understand the difference in joint life expediencies to better improve the conversations I have with clients.

-

Thank you for the comments, both Mr. Wilson and demendels. Our research does not actually make a negative inference in our projections from the past performance in other countries. We only present this as a possibility, but not an element of our calculations. In short, if the long-term equity performance of the equity market were to look like the more developed countries of the 20th century, then our projections would be more negative. Dr. Pfau has not hidden agenda, and my company, WealthVest, does sell annuities to major broker-dealers. However, the key facts remain the same---after including mutual fund management fees, advisor fees and today's stock and bond market valuations--today's investor is likely to achieve low returns in the near term and this will negatively impact their sustainable withdrawal rate. The inclusion of all of these data points (plus a more up-to-date view of longevity) seems essential for near-retirees and retirees as they attempt to plan the safe withdrawal rate over their lifetime for their savings.

-

While the long-term experience of US markets may be limited, I am not sure that simply combining it the experience of other countries help-s a great deal. I found it interesting that the four countries with the lowest success rates were the same countries that probably endured the worst damage from both WWI and WWII. Italy, Germany and France all went through multiple government collapses and Germany suffered hyper-inflation during the Weimar regime the likes of which has never been seen in either the US or any number of other countries. Germany was also saddled with enormous reparation payments post-WWI as well as strict limitations on industry. A number of the countries were dependent upon colonial empires to support their economies and saw those wither away after the two world wars. Of the countries with success rates less than 75%, all suffered war on their sovereign territory and/or were occupied by invading forces for years. Interestingly, of the 9 countries with success rates greater than 75%, 6 were not occupied during either world war, two were not fully independent states until after 1900 (RSA 1931, AUS consolidated multiple indpendent territories in 1901). While one can make many arguments as to why 4% may or may not be sustainable but it seems to me that comparing countries with such widely different diverse political, military and economic experiences is a misuse of history.

-

Let's start with the end, few would argue against the notion that a 2% withdrawal rate is "safer" than a 4% withdrawal rate. For that matter a 1% withdrawal rate is "safer" than a 2% withdrawal rate, and a 0% withdrawal rate is unquestionably safer still. However, as anyone who has sat down with a client facing retirement knows, these even "safer" withdrawal rates have significant drawbacks of their own. No one can predict the future, certainly not I, and to his credit, neither to my knowledge did Bill Bengen. What he did try to do, though, is to learn from the past. It was based on those lessons, that the "4% rule" was born. If anyone ever presented the "4% Rule" as a guarantee of success they either never read any of the studies on which it was based, or grossly misrepresented them. That argument is simply what philosophers call a "straw man", a weak argument that misrepresents another's point of view presented solely because it is so easy to knock down. The authors refer to data from other countries dating back to 1900. That sounds impressive, but fundamental to the "4% rule" is the notion of annual adjustments to account for changes in the cost of living. Yet in none of those countries, or anywhere else for that matter, was anyone even tracking changes in the cost of living. While I have not studied it extensively, my understanding is that did not start in even its crudest form until the 1920s when it started here, so it far from clear how relevant that analysis is. The importance of a having a sound basis for calculating changes in the cost of living is underlined by looking at just where the failures started to occur in Bengen's analysis when he tried to plug in higher withdrawal rates. The failures did not occur, as the authors would have you infer, due to the poor sequence of returns that confronted those retiring just before the great stock market crash of 1929, but with those who retired just before the onset of the great inflation of the 1970s. Upon reflection, the greater impact of early onset inflation over early market downturns actually makes sense. If we think about it, the impact of low or adverse returns in the early years is limited to the withdrawals made during those early years. The remaining funds are able to recover later when the returns are better. The impact of early inflation, though, is cumulative and, baring an equal or greater period of subsequent deflation, it is irreversible and compounds over time. It is of course, true that we have no reason to expect history to repeat itself. The disclaimer that "past performance..." need not be repeated for this audience. However, the use of Monte Carlo analysis has its limitations as well. It is highly dependent on the assumptions built into the model being used. Is there any reason to believe that those assumptions will be any more predictive of the future? The authors refer to historical precedent to justify their assumptions which is curious since they then argue for using their model that relies on those assumptions to argue against relying on historical precedent which seems rather selective on their part. Finally, the authors' hidden agenda here, that annuities are a better alternative is problematic as well. Keep in mind that insurance companies are not magical investors. They would be investing right along side the rest of us in that dismal environment. Does anyone seriously believe that insurance companies are that much better at investing than the rest of us? They certainly have far less flexibility. And if they can't make the returns required to support the promised payouts, they don't have the flexibility to make adjustments. They are committed to making the promised payouts until they can no longer at which time they will fail. When they fail, they can only fail catastrophically which would leave those dependent on them far worse off than those who might have had to cut back a bit in their latter years. The "4%" rule is not now, nor was it ever any kind of a guarantee of what the future has in store for us. That is, always was, and probably will be for the forseable future, unpredictable. It is a rule of thumb, but a rule of thumb based on an effort to learn from the lessons of the past. There is no question that anyone who suggest that it be blindly followed is committing gross malpractice. But if I have to chose between suggesting to my clients that they base themselves on that rule of thumb or suggesting that they halve their lifestyle based on some algorithms cooked up by the authors, I think I'll stick with the "4% rule", thank you very much.