How do you describe public policy that is so flawed it fails the very people it claims to serve? This is the question I am wrestling with in the context of the Department of Labor’s new fiduciary rule. Among the fiduciary rule’s many deficiencies, the most significant is the likely outcome that individuals with low balances, including many from underserved communities, will be disenfranchised from the professional financial guidance that they desperately need.

I do not for a moment believe that the individuals at the Department of Labor who wrote this rule intended this outcome. My assumption is that their aims are noble. But that doesn’t change the fact that the fiduciary rule is unnecessary and ill advised, and likely to damage Americans’ retirement security more than strengthen it.

Again, I do not question the motivations of the Department of Labor’s employees. What I question is what seems plain: That they lack an understanding of what constitutes retirement security. Because it’s not the accumulation of assets. Yet, it is assets that the DOL seems most focused on.

In 2000, a risk averse retiree with $1 million could have purchased 6-month CDs and collected $5,700 per month in interest income. By 2021, that retiree’s interest income had plummeted by 99%, to just $75/mo. It is not about the “money.” In this example, the money never changed. Rather, it is and always will be about the “income.”

Had the fiduciary rule placed greater emphasis on the creation of and protection of income, it would have better served the financial interests of millions of retirees. And because in this context the rule is so flawed, I believe advisors of every stripe should hope the fiduciary rule is ultimately vacated.

The Illogical Commission Prejudice

It seems to me that the Department of Labor has historically preferred fee-based advisor compensation over commissions. In addition, many in the RIA community tend to look down on insurance agents, in large part due to their commission-based compensation model. For a simple reason, favoring the fee-based compensation model never made sense to me. The simple reason is the fee-based model is more expensive for the retirement investor to bear.

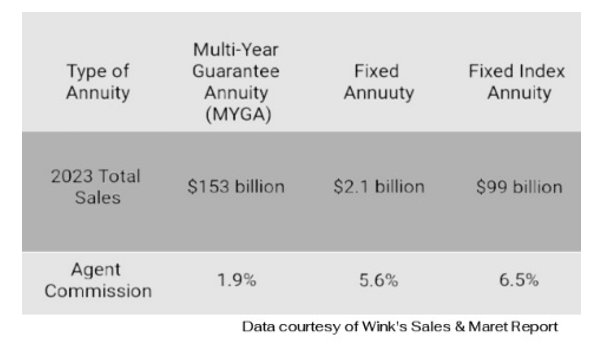

Consider the example of an insurance agent receiving a 7% commission on a $100,000 IRA rollover sale that is funded by a 10-year fixed index annuity. The agent would be entitled to a one-time commission equal to $7,000, which is paid entirely by the insurer, not the purchaser, if the contract is held to the end of the surrender charge period.

Over the same 10-year period, an investment advisor managing the same $100,000 in an account that grows by 6% annually, would be paid $13,932, all of which is borne by the retirement investor in the form of small, systematic transfers of some of the investor’s wealth to the investment advisor. These systematic transfers of the retirement investor’s wealth take the form of a direct cost debited from the investor’s investment account.

By contrast, the retirement investor who holds the fixed index annuity for 10 years pays nothing. The reason is that after 10 years the deferred sales charge (surrender charge) has expired. Said differently, the retirement investor in this example saved about $14,000 by choosing to work with an insurance agent.

But that is not the whole story. When working with a fee-based investment advisor, the genuine cost borne by the retirement investor is likely to be higher than $14,000. Consider that once the investment fee has been debited from the investor’s account, any investment gains that would have been generated on those monies can never be realized, potentially making the investor’s effective cost significantly more than $14,000.

Let me be clear. By describing this example, I do not mean to diminish the importance of investment advice or impugn advisors who are compensated by AUM fees. Nor do I mean to say that choosing to work with an agent is inherently superior due to cost effectiveness. Defining either one as superior is simply a false comparison, just as it would be a fallacy to declare that your car’s fuel pump is superior to its brakes. The fact is, for your car to operate both are unquestionably vital.

Regulatory Unfairness

In 1987, the SEC thought it wise to regulate financial advisors and investment advisers in the same manner. This was a blunder of enormous proportions, in my judgment. There is no regulatory framework that enables agents to be compensated for advising. They can only be compensated for product sales. So, when certain members of the RIA community disparage insurance agents, looking down on them because they sell “products” and earn commissions, they should understand that insurance agents have no other way of being compensated. They should also understand that the liability minimization that insurance agents provide, especially in the context of retirees and retirement income planning is of first order importance.

For millions of American retirees, liability management is the foundational dimension of an investing strategy that seeks to generate income (I explore this further below).

The regulatory discrimination against Insurance agents is a big issue. If you’d like to know more about this, the individual who more than anyone else has best articulated this regulatory asymmetry is Michelle Richter-Gordon. A good place to start is Michelle’s LinkedIn page: (7) Michelle Richter-Gordon | LinkedIn

The Two Colors Of Money

Thirty years ago, I developed an analogy to describe an important nuance about money. I would typically explain this nuance in a seminar setting. At a certain point in the seminar, I’d reach into my wallet and pull out two one-dollar bills. One of these bills I had dyed bright red. The other remained green. I would hold up both and explain to the audience that there are two colors of money. Taking the red dollar bill in my right hand I would say:

“Red money is hot money. It seeks the highest possible rate of rate of return. Red money might return a big profit or result in a big loss. Red money is the money we invest.”

Then, taking the greed dollar bill in my left hand, I would say:

“Green money, on the other hand, accepts no risk at all. It seeks stability. Green money is satisfied with a lower rate of return because the risk of loss is eliminated. It’s the thought of losing their green money that keeps people up at night. Green money is the money we save.”

When I asked the audience to indicate by a show of hands which color of money they preferred, more people would indicate their preference for green money. But I would explain that one color of money is not inherently better than the other. Most people, especially retirees, need a thoughtful blend of both.

What The Department Of Labor May Not Understand

I speculate that the folks making decisions at the Department of Labor do not understand income planning in the context of serving the best interests of constrained investors. I only wish they did. I have spent much of the past 10 years working on the issue of strengthening retirement security for this large segment of retirement investors.

If you’re not familiar with the term constrained investor, I’m referring to millions of Americans who reach retirement with savings. But the amount they’ve saved is not high in relation to the level of monthly income they must generate in order to support a minimally acceptable lifestyle.

Here I will draw your attention to two extraordinarily principal issues:

1. All constrained investors share an absolute reliance on their savings to produce the monthly income that they must have, and,

2. In retirement it’s your income, not your wealth, that creates your standard of living.

These realities explain why, financially, income is everything to a retiree.

A Question For The Department Of Labor

A defining characteristic common to all constrained investors is that they share an absolute reliance on their savings to produce monthly income they must have. Therefore, when working with constrained investors, the financial advisor’s foremost priority must be the mitigation risks that can reduce or wipe out the investor’s capacity to generate income from savings. I see no legitimate challenge to this assertion. And because the statement is true, any financial advisor intending to serve the best interests of constrained investor’s must, at a minimum, take steps to mitigate risks that can impair income generation in both the short-term (timing risk) and long-term (longevity risk).

In my view, the Department of Labor would perform a far greater service to the people of America if they promulgated a rule that explicitly required investment advisor fiduciaries to safeguard the retirement investor’s capacity to generate lifelong income. This issue is so profoundly important and transparent on its face, I cannot see how an advisor who ignores risk mitigation can serve the retirement investor’s best interests.

So, to the good people at the Department of Labor I pose two questions:

1. Does an investment advisor fulfill the fiduciary requirement when he or she places the investor’s money in a fee-based account that affords no protection against longevity and timing risks?

2. Does an insurance agent fulfill the best interest requirement when he or she employs an annuity or a combination of annuities to protect the investor against longevity and timing risks?

Because this critical assessment of the retirement investor’s true needs has been neglected in the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule proposal, an important opportunity to advance the financial health of millions of constrained investors has been missed. And insurance agents and the annuities they sell have been unfairly targeted.

It’s important to understand how badly the Department of Labor has misfired here. Constrained investors represent the majority of individuals who reach retirement with savings. Constrained investors represent the majority of “boomer” women. Constrained investors represent the majority of retirement investors from underserved communities. In terms therefore of best serving the interests of American retirement investors, how do we conclude anything other than the Department of Labor is guilty of nothing less than a massive failure.

To be clear, not for a moment do I think this failure is intentional. Rather, I judge that it’s due to the lack of understanding of nuanced retirement income planning and the nature and needs of constrained investors.

Ultimate Irony: The Need For Annuities

The ultimate irony coming out of the Department of Labor’s fiduciary rule proposal is that to truly serve the best interest of the majority of retirement investors, annuities are the most needed of all financial products. This is because constrained investors, at a minimum, require “flooring,” a source of reliable and lifetime monthly income that, when added to Social Security, provides an income in an amount that can at least meet the retirement investor’s most essential living expenses.

To operate safely as ERISA fiduciaries, therefore, it is in the construction of “flooring” strategies, comprised of annuities, that agents must focus. The practical effect of DOL is to force agents to think narrowly and strategically, focusing solely on the “flooring” aspect of retirement investing. This strictly keeps the agent in compliance with the limitations of his or her licensure. It also assures that the agent is operating in the constrained investor’s best interests.

The Tragic Neglect Of Millions Of American Savers

One of the tragic outcomes I see resulting from the DOL’s fiduciary rule, if it persists in practice, is that the segment of the population that most needs the guidance of a financial expert is likely not to receive it. Let’s be frank. Most investment advisors, most financial planners and most hybrid financial advisors have no interest in working with clients with low investment balances, or who have no accumulated assets but possess only the capacity to save a modest amount of money each month. It is the insurance community that nobly and proudly has served these individuals. And in countless cases, the monetary interests of these less affluent Americans have been enhanced with annuities and life insurance.

How is it beneficial to the health of this country if the net effect of the fiduciary rule potentially deprives millions the opportunity to receive personal financial guidance? Does the Department of Labor believe that once the rule is in effect, financial advisors who historically have shown no interest in working with clients with low balances will all of a sudden seek them out?

It seems to me that a better public policy would be to create incentives for the insurance community, or even the larger financial advisor community, to embrace the large segment of Americans who have yet to accumulate significant wealth. But I see nothing in the fiduciary rule that will enable this. This is why I believe that all financial advisors should oppose the DOL’s proposal. Any policy that is likely to result in this segment of Americans being further distanced from professional financial guidance should be vacated by the Courts.

The Effort To Vacate The Fiduciary Rule

In the beginning. I said that the DOL’s fiduciary rule is an unnecessary, ill advised, and ultimately harmful regulation that is likely to prevent many Americans from receiving much needed professional financial guidance. I hope I have made my case.

The effort to defeat the proposed rule has been led by the non-profit Federation of Americans for Consumer Choice (FACC). I serve as Board Advisor to FACC. FACC’s mission is to preserve and strengthen the independent distribution of insurance products. FACC is led by CEO, Kim O’Brien and Board Chair, Mary Ann Lacey-Gray.

In February 2022, FACC sued the U.S. department of Labor to challenge the DOL’s reinterpretation of the 1975 five-part test that determines who is deemed to be an ERISA fiduciary. FACC took this action because the DOL’s reinterpretation would have the effect of categorizing insurance agents as ERISA investment advisor fiduciaries in the context of IRA transactions.

A significant reason for suing the DOL was FACC’s desire to preserve consumer choice. FACC believes that the DOL’s incursion into State regulated insurance is an unneeded power grab. Insurance agents are already obligated under the NAIC’s model law to serve the client’s best interests. The model law has been adopted by 47 states. Moreover, FACC believes that DOL’s proposed rule runs counter to the 5th Circuit Court decision that vacated the DOL’s earlier attempt to impose the fiduciary rule.

In the context of the DOL’s October 31, 2023, publication of its most recent fiduciary rule proposal, FACC’s lawsuit has taken on monumental importance. Any right-thinking financial professional who cares about the perseverance of consumer choice, and the millions of Americans who need professional financial guidance but are typically served only by the insurance community, should take measures to support FACC.

Individuals with the most direct interest in vacating DOL’s proposal- the community of insurance agents, insurance marketing organizations, insurance carriers and insurance trade associations—should support FACC’s legal challenge in every conceivable manner. There is too much at stake for anything less.

In Conclusion

Let me recapture some of the most important points I’ve attempted to make in this article.

1. The DOL’s proposal is an unneeded and misguided plan for “protecting” retirement savers that will serve to accomplish the opposite of its stated objective.

2. DOLs preference for fee-based compensation costs retirement savers more money than they would pay when purchasing annuities from commission-based insurance agents.

3. The DOL’s proposed fiduciary rule ignores the most important aspects of retirement income planning and will serve to weaken the retirement security of millions of America’s constrained investors.

4. The DOL’s apparent dislike of fixed index annuities ignores what may well be the most important financial value proposition ever created: the opportunity for growth, without the risk of loss.

5. The DOL completely misses the nuance that retirement investors need two types of money. It fails to differentiate between saved and invested money.

6. The DOL’s proposal fails to explicitly require that financial advisors working with retirement investors take steps to mitigate the risks that can reduce or wipe out the investor’s capacity to generate income from savings. If the DOL wishes to truly strengthen the retirement security of millions of constrained investors, it should publish a rule that addresses this critically important planning need and, minimally, encourage or even mandate the use of lifetime income annuities.

7. Insurance professionals cannot reasonably operate in their clients’ best interests unless they manage risks that the DOL has thus far chosen to ignore.

8. Because a retiree’s standard of living is a function of his or her income, not wealth, the DOL missed an opportunity to change the conversation with the American people. The DOL could have put the emphasis on income and protection, inducing an outcome that strengthens rather than weakens the financial security of millions of American families.

9. The DOL could have acted to boost the national economy by encouraging or incentivizing the use of lifetime income annuities. Over time, this course would likely reduce reliance on the Social Security system and other entitlement programs.

10. The DOL’s actions ill-serve the monetary interests of millions of individuals from underserved communities.

My sincere hope is that the DOL fiduciary rule will be vacated. But even more, my hope is that those making decisions at the Department of Labor will become educated about the most important needs retirees face, especially the millions of America’s constrained investors. Let me be clear. In criticizing the DOL’s decisions, I believe they are acting in what they sincerely view as serving the consumer’s best interests. The problem is a lack of understanding about what serving a retirement investor’s best interests truly means.

Wealth2k founder, David Macchia, is an entrepreneur, author and public speaker whose work involves improving the processes used in retirement-income planning. Macchia is the developer of the Constrained Investor planning framework. He is developing income planning tools and processes for use by ERISA fiduciaries. He is also creating solutions to mitigate the threat to human financial advisors that is posed by emerging AI competitors.