The history of epidemics is rife with examples of society rebelling against tough public-health edicts, such as the breach of plague quarantine in 18th-century Marseille or protests against face masks during the 1918 influenza pandemic. The grim consequence is a fresh wave of deadly infections.

Covid-19’s million deaths may pale in comparison to the estimated 50 million lives lost in 1918, but the cycle risks unfolding again. France, the U.K. and Spain face a triple threat: A jump in cases, a population exhausted by lockdown-induced recession, and rising resistance to tougher measures.

Curfews and closures of restaurants and bars have seen business owners literally throw their keys to the ground in present-day Marseille. In Madrid, protesters have bristled at a targeted local lockdown they view as discriminatory. It’s not just conspiracy theorists on the streets in London and Berlin who are angry.

Those protesting shouldn’t be dismissed as the selfish exceptions to the rule. Beyond the vocal minority, there are signs that the silent majority is also losing faith in increasingly bureaucratic strictures. Policymakers need to restore it.

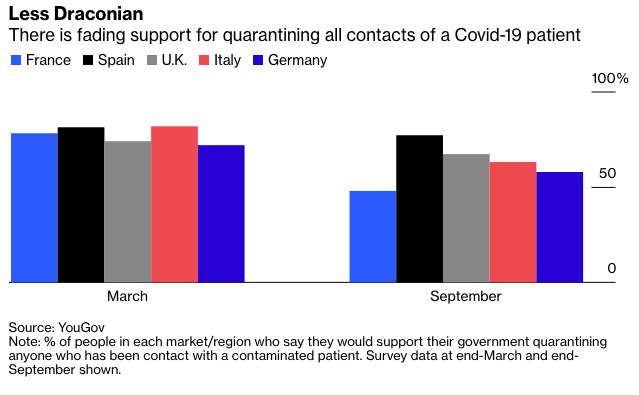

While respect for mask-wearing and personal hygiene is broadly high, according to YouGov surveys of European countries, support for quarantine and self-isolation is wavering. In France, only 48% of people currently support quarantining those who’ve had contact with infected patients, down from 78% in March. It has also fallen in the U.K. and Spain, though to a lesser degree.

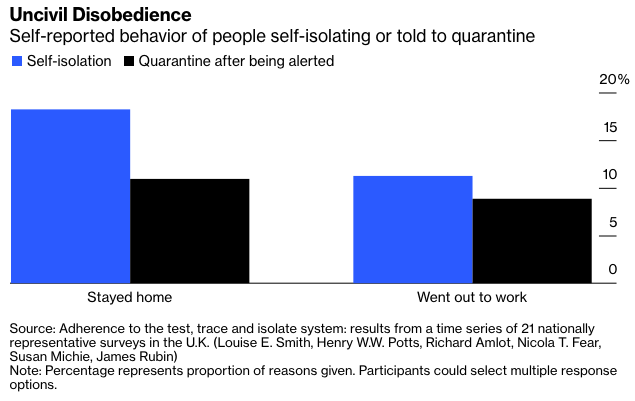

There’s mounting evidence that people who are asked to stay at home aren’t doing so. A recent King’s College London survey in the U.K. of over 30,000 people between March and August found that only 18.2% reported remaining at home after developing symptoms and a measly 10.9% after being alerted by contact tracers. That’s worrying given the critical importance of self-isolation in breaking chains of transmission before they reach the vulnerable and the elderly.

Obviously being cooped up is nobody’s idea of fun, and it brings the psychological stress of altruistically choosing long-term pain over short-term pleasure. But for those who don’t have the luxury of jobs they can do from their kitchen table, isolation also means being deprived of a decent wage. Around 10%-11% of respondents cited “going out to work” among reasons for non-compliance. That echoes an earlier finding that half of Britain’s low-income workers couldn’t actually afford to self-isolate because mandatory sick pay is so low, according to the Trades Union Congress. Other reasons given included caring for a vulnerable person (10%-12%) and mental stress (8%-11%).

This isn’t the case for all countries. In Austria, where quarantined workers are entitled to be paid as normal, compliance is over 98%, according to the Washington Post. A lot of focus has been put on European countries’ approach to lockdown, but relatively little on their welfare systems, reckons Joan Ramon Villalbi of Barcelona’s Public Health Agency. The OECD is rightly encouraging countries to extend sick leave and other benefits to more workers, especially the self-employed. Europe should, too.