The Deutsch-Fidelity saga is a cautionary tale. It shines a harsh light on the perils clients can face as financial behemoths seek to manage competing interests within their own ranks. And it underscores the risks that countless investors, drawn to the allure of all things Chinese, take while pursuing opportunities in its quickly growing economy. Deutsch’s investment in China Medical might have sunk to zero no matter how his brokerage had behaved.

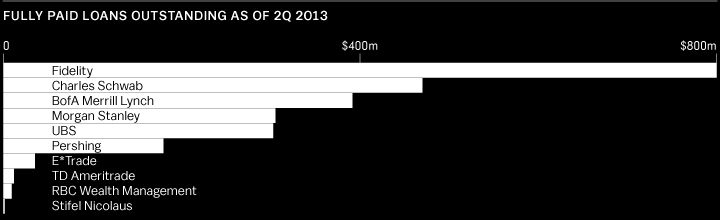

The affair also raises questions about the methods Fidelity used to build a sizable business lending out shares its clients own outright—a practice known as “fully paid lending.” Deutsch claims he was a victim of inappropriate share lending. For its part, Fidelity, the largest player in the fully paid share-lending business, says it didn’t lend out Deutsch’s shares under its fully paid lending program but rather under the authority it says it has to lend shares out of a client’s margin account, according to people familiar with the company’s views. “We have strong and thorough control and compliance processes in place for all aspects of our business, including securities lending,” says Fidelity’s Banker. “Clients who choose to open a margin account sign margin agreements that consent to securities lending.”

The athletically built Deutsch grew up in the suburbs north of Manhattan. Mathematically inclined from an early age, he attended Franklin & Marshall College in Pennsylvania, where the 6-foot-3 power forward led the basketball team in scoring for two seasons. After graduating in 1984 with a degree in accounting, he joined the wine-importing business his father, Bill, also an accountant, had set up in their home in 1981. Together they mounted an assault on wine snobbery, building Deutsch Family Wine & Spirits into one of the country’s largest importers over the next two decades. In the process they introduced Americans to Beaujolais Nouveau from France and for a time turned Australia’s Yellow Tail, with its memorable kangaroo label, into the top-selling imported wine in the U.S.

The business—now headquartered in White Plains, N.Y.—provided Peter, a divorced father of three, with the means to indulge his appetite for investing. He’s a guarded man in some ways; he’s loath to say much about his lake home, for example. But he’s not shy about his appetite for aggressive investments.

Deutsch’s path to Fidelity began with Tom Steffanci Jr., the wine company’s president, who introduced him to AER Advisors of North Hampton, N.H. The firm, run by the husband-and-wife team of David and Carol O’Leary, originally came to the Deutsches to discuss currency-risk hedging for the wine business. David, a chartered financial analyst, had worked at Fidelity until 1994, when he left and set up Alpha Equity Research, which provided investment research to his old employer and others. It eventually evolved into investment adviser AER.

Peter Deutsch became a client and fan. He even did some investing on his own using AER’s trading models. With them, he bet millions, buying Direxion triple-leveraged and inverse ETFs via a Fidelity brokerage account he’d had since 2000. By late 2011 he’d pocketed more than $60 million, according to him and David O’Leary.

Deutsch says his investment activity caught the eye of a Fidelity representative, who connected him with FFOS. In October 2011, FFOS sent half a dozen employees to meet with Deutsch near his Connecticut home. As part of Fidelity, FFOS can offer a range of big-bank services, such as securities research and trust management. “One of their missions is to leverage the technology and resources of Fidelity,” says Greg Kushner, founder of Beverly Hills-based Lido Consulting, which manages and advises family offices. “They’ve used it to build a pretty substantial mix of clients across the country.”

And yet, FFOS, the brainchild of Fidelity founder Ned Johnson, is a far cry from the private-banking world of walnut paneling and bone china. Located in Boston’s trendy Seaport district, the division has a distinct startup vibe; it’s a world apart from Fidelity’s headquarters downtown, a few blocks away. A promotional video on YouTube shows employees celebrating excellence on the job by tossing toy fish to one another. A tieless Jeff Bezanson, vice president of Relationship Management, who became Deutsch’s rep, says in the video that when on the phone, customers relish the blast of a bullhorn the sales staff uses to mark “a good client experience.” (Fidelity declined to make Bezanson or other employees available.)

YouTube: Experience the culture at Fidelity Family Office Services

Deutsch would need all the goodwill and advice he could get. At about the time FFOS was wooing Deutsch, O’Leary—who remained his investment adviser—got him interested in a new strategy. The wild China boom that, among other things, brought hundreds of Chinese stock listings to the U.S. had also led to a spate of outright frauds. Investors fled the sector. Valuations plummeted. Still, O’Leary believed quality stocks had gotten crushed along with junk ones. He compiled a list of a dozen beaten-down companies—some trading for as little as one times earnings—that an investor could ride back to health. O’Leary dubbed his strategy China Gold.

Source: Finadium estimates.

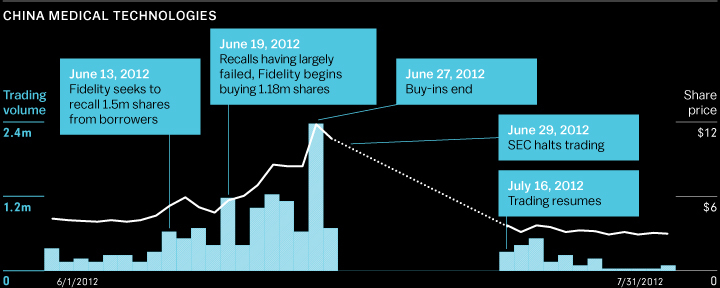

Source: Bloomberg, court records.

As Deutsch recalls, FFOS offered to welcome him and his money into what was then an elite constellation of 300 families worth a total of $30 billion. An FFOS brochure says it provides clients with the chance to network with other “families of wealth” and enjoy “a conflict-free client service model in which we put our clients’ interests first.” The pitch, Deutsch says, aligned nicely with the way he and his father had done business with winemaking families around the world. “I left Fidelity that day feeling like I’d found a new family partner,” says Deutsch, whose family eventually had at least $155 million at the firm.