With private equity firms sitting on a record amount of cash they’re struggling to invest, their clients are turning to exchange-traded funds for relief.

BlackRock Inc. and State Street Corp., two of the world’s biggest providers of ETFs, say an increasing number of institutional investors are using their products to park money earmarked for private funds. These investors -- pension plans, foundations and endowments that are under pressure to meet obligations -- are trying to eke out an extra return on cash that would otherwise languish in a money market fund.

“They can’t afford to have money sitting in cash or similar low-yielding investments,” said Armit Bhambra, who works for BlackRock’s iShares U.K. institutional team from London. “It’s difficult to justify sitting in cash for 24 months, so they’re having to think about different ways to fund these types of mandates.”

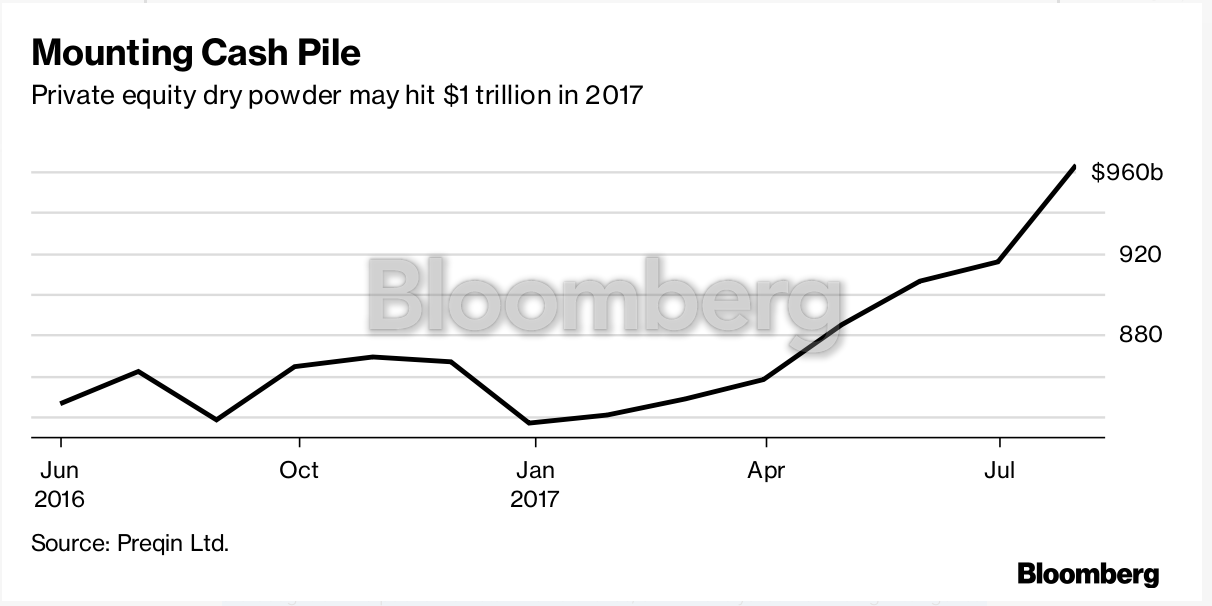

The amount of dry powder -- money raised but not yet invested -- could hit $1 trillion by the end of year in private equity alone, after reaching $963 billion in July, according to researcher Preqin Ltd. That’s pushing out the average time it takes for new commitments to start being invested to as long as three years, up from one year previously, according to State Street.

“The ability to deploy capital quickly has diminished,” said Chirag Patel, head of innovation and advisory for State Street in Europe. “Investors need liquidity to quickly fund potential capital calls, which is very unattractive in this environment, so the more often chosen route is to deploy against a capital-weighted index. They are buying index exposure.”

ETFs, which have grown to more than $4 trillion in assets, can give investors instant and diversified exposure to an asset class, while allowing for a quick liquidation to meet obligations. Unlike traditional money funds, they are exposed to the ups and downs of the underlying markets, and there’s some debate about how liquid ETFs really are when they track inherently illiquid assets such as junk bonds.

‘Clock’s Ticking’

‘Clock’s Ticking’

The funds, which typically mirror the performance of an index and can be bought and sold throughout the day like a stock, have long been popular with retail investors because of their ease of use and low fees. Institutional investors have been slower to embrace them, with only about one in five U.S. institutions currently investing in them, but that number is quickly increasing, according to Greenwich Associates, a financial-services research firm.

BlackRock, which oversees almost $1.5 trillion in ETFs globally, has been pitching the products to institutions as simpler substitutes for single securities and derivatives used in the past to manage cash. It says its pension clients, at least in Europe, are increasingly using ETFs to create so-called liquidity sleeves for their portfolios.

“Until we find individual assets that we find attractive, we’ll buy the ETF,” said Leighton Shantz, the Austin-based director of fixed income at Employees Retirement System of Texas, which manages about $27 billion for state workers. “The clock’s ticking, you’re going to underperform because you’re going to pay the added management fee, but it at least gets you closer than if you’re sitting in cash.”