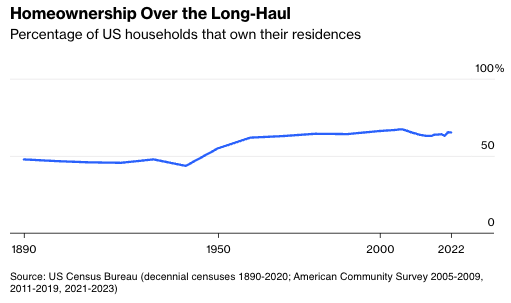

Since taking a big leap upward in the 1940s and 1950s, the homeownership rate in the U.S. has been remarkably steady since the 1960s, with close to two-thirds of households owning their homes.

Yes, there was an increase during the 2000s housing boom and a decrease during the bust, but a different Census Bureau survey found that the homeownership rate in the second quarter of this year was, at 65.9%, about where it was in the late 1990s and late 1970s. Since the 1970s, inflation-adjusted house prices (measured using the FHFA House Price Index and the Consumer Price Index) have almost doubled, yet homeownership has not declined.

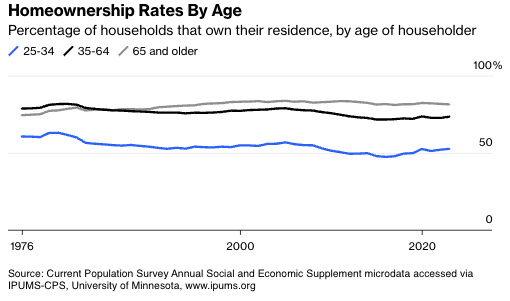

Look at homeownership rates by age from yet another Census Bureau survey, the Annual Social and Economic Supplement conducted every February through April as part of the monthly Current Population Survey from which the unemployment rate is derived, and you do see some movement. The homeownership rate is up since 1976 for Americans 65 and older, but down for younger adults.

It’s not down all that much, though. At 52.7% as of earlier this year, the rate for those aged 25 through 34 was about 10 percentage points below its late-1970s level and four points less than in the mid-2000s. But it’s close to where it was for most of the 1980s and 1990s, and all-in-all there’s not much here to stoke concern that today’s young adults—who are still mostly members of the giant millennial generation, which currently ranges in age from 26 to 42—are missing out on homeownership and its attendant economic benefits relative to Gen Xers or even younger baby boomers. More than half of them own homes!

But wait — that percentage sounds high. Do 52.7% of 25-to-34-year-olds really own their homes?!?!

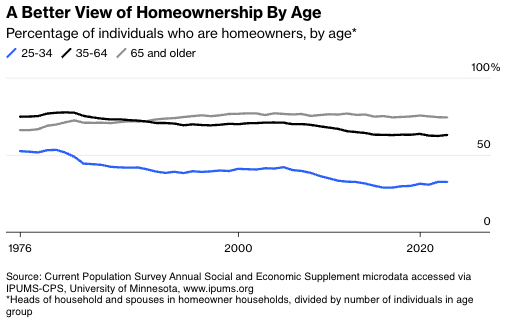

No, they don’t. The homeownership rate as customarily reported by the Census Bureau is measured by household. Of the 25-to-34-year-olds who are heads of a household, 52.7% own their own homes. But of all the 25-to-34-year-olds in the U.S., only 32.6% do, down 20 percentage points from the late 1970s and almost 10 points since the mid-2000s.

I am not the first person to notice this divergence. Urban Institute researchers Laurie Goodman, Jung Hyun Choi and Jun Zhu wrote about it in April, and Census Bureau economist John Voorheis has brought it up from time to time on Twitter/X. It was a thread last week by Voorheis that inspired me to extract the data myself from the University of Minnesota’s IPUMS-CPS database, which contains individual responses to the CPS, masked and in some cases altered to protect respondents’ privacy.

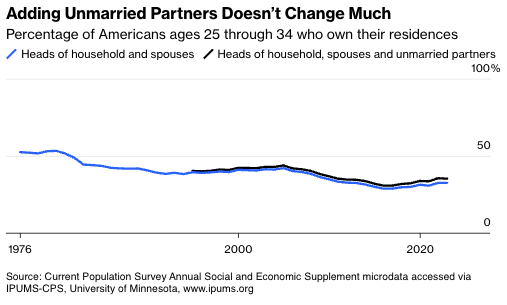

To get the homeownership rates, I added together the estimated number of homeowning heads of household and spouses of homeowning heads of household in each age group and divided that by the total number of people in that age group. Falling marriage rates could thus be responsible for some of the downward pressure on homeownership rates. But from 1995 onward there’s data on unmarried partners too, and while including them reduces the 25-34 homeownership decline since then by two percentage points, it doesn’t really change the overall picture.

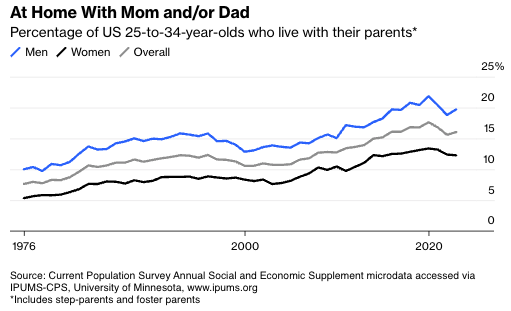

This decline has coincided with a big increase—especially since 2000—in the percentage of young adults living with their parents. The following chart is derived from the same survey as the previous three; other Census surveys have found the same trend but even higher rates (unlike the other charts this one doesn’t go all the way to 100%, because it would be hard to see what’s going on if it did).

Why are young people, and especially young men, so much likelier to live with their parents now than in the past? A 2021 Pew Research Center survey of adults living in multigenerational households found that 40% attributed it to financial issues, 33% to caregiving needs and 28% said it’s just “the arrangement they’ve always had.” Clearly there are societal/cultural forces at work here, with immigrant households more likely to be multigenerational and men much more likely to live with their parents than women. But economic conditions matter too, as indicated by the declines in the living-at-home share in 2021 and 2022—probably the best time in decades to be a young worker entering the labor market. The same Urban Institute trio cited above has found that the economic cause-and-effect may go in both directions, with those who delay leaving their parental home much less likely to become homeowners later, harming their long-term financial prospects.

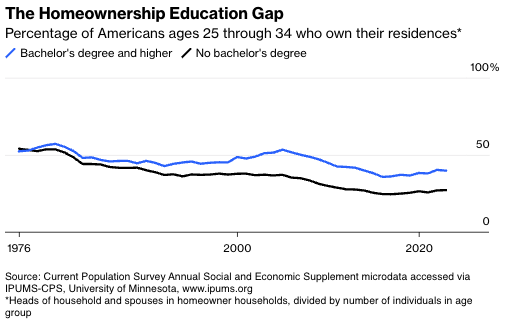

Also revealing is the breakdown by education. In the mid-1970s, young adults who hadn’t finished college were more likely to own their homes than those who had, as those in school for longer formed households later. Over the next two decades, the much-worse employment prospects for those without college degrees flipped the two rates and then drove a growing wedge between them. The wedge stopped growing during the Great Recession, and the two lines have been moving more or less in tandem since.

However you measure or slice it, there has been a modest resurgence in young-adult homeownership since 2016. It appears to have stalled earlier this year amid rising interest rates. A recession would almost certainly throw it into reverse. Let’s hope that doesn’t happen.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business. A former editorial director of Harvard Business Review, he is author of The Myth of the Rational Market.