To invest in Berkshire Hathaway Inc. means to give Warren Buffett the benefit of the doubt. That's both the beauty and potential drawback of the $392 billion company.

Take this section of Buffett's annual letter to shareholders in February discussing certain adjustments made to operating expenses within Berkshire's manufacturing division, which comprises the recently acquired Precision Castparts business:

"We present the data in this manner because Charlie (Munger) and I believe the adjusted numbers more accurately reflect the true economic expenses and profits of the businesses aggregated in the table than do GAAP figures. I won’t explain all of the adjustments -- some are tiny and arcane -- but serious investors should understand the disparate nature of intangible assets. Some truly deplete in value over time, while others in no way lose value."

The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission wasn't satisfied with this "just-trust-me" precept and sent a letter to Berkshire on Sept. 8 asking for clarification on two things: how the unit's net earnings were impacted by such adjustments, and why $17 billion of its customer relationships and trade names can be determined to have indefinite lives.

So as not to bore you with the accounting details, here's the short version of the Oct. 6 response from Berkshire CFO Marc Hamburg, which was released Monday along with the SEC's initial query: First, the acquisition accounting expenses were considered corporate expenses. And second, as a components maker for the "oligopoly" that is the aerospace industry, Precision Castparts' customers aren't going anywhere for the foreseeable future, meaning they shouldn't lose value and will continue contributing to the business's cash flow indefinitely.

Fair enough. No juicy impropriety here, and in fact the SEC said in an Oct. 21 response that it had completed its review of the matter. However, it does shine a light on an issue that will most certainly become a point of contention when Buffett, 86, is no longer running the conglomerate.

Let's face it, Buffett -- for mostly good reason -- isn't always held to the same standard as other CEOs because of his celebrity and track record. A lot of the time we're taking his word for it because his word has been good.

Berkshire is one of the few large public companies that still doesn't hold quarterly earnings calls with analysts, which as Gadfly's Brooke Sutherland pointed out this week, makes it rather old-timey. There's only the annual letter and big shareholder meeting down in Omaha, Nebraska, where you can catch Buffett playing ping-pong, strumming a ukulele and gulping down a Cherry Coke, all of which plays into the folksy persona that adds to his aura of trustworthiness.

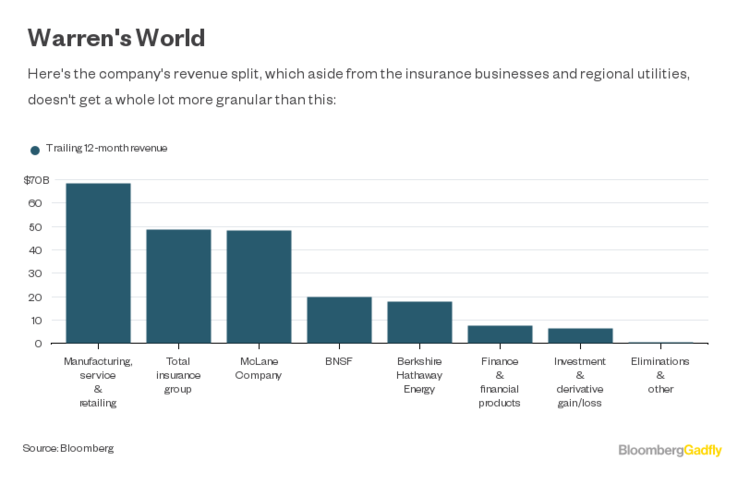

That's in spite of the transparency shortcomings in Berkshire's financials. For example, look at all the individual companies that fall under Berkshire's manufacturing division:

How many of those does Berkshire break out quarterly results for? None. The closest you get are revenue and pre-tax earnings for three high-level groups within manufacturing: industrial products, building products and consumer products. And this division accounted for 20 percent of Berkshire's trailing 12-month revenue and about a quarter of pre-tax income.