Women are returning to the U.S. labor force in greater numbers this year, helping arrest an ugly decline in the so-called participation rate. Just how much additional support they can lend the economy over the longer term depends on their continued involvement.

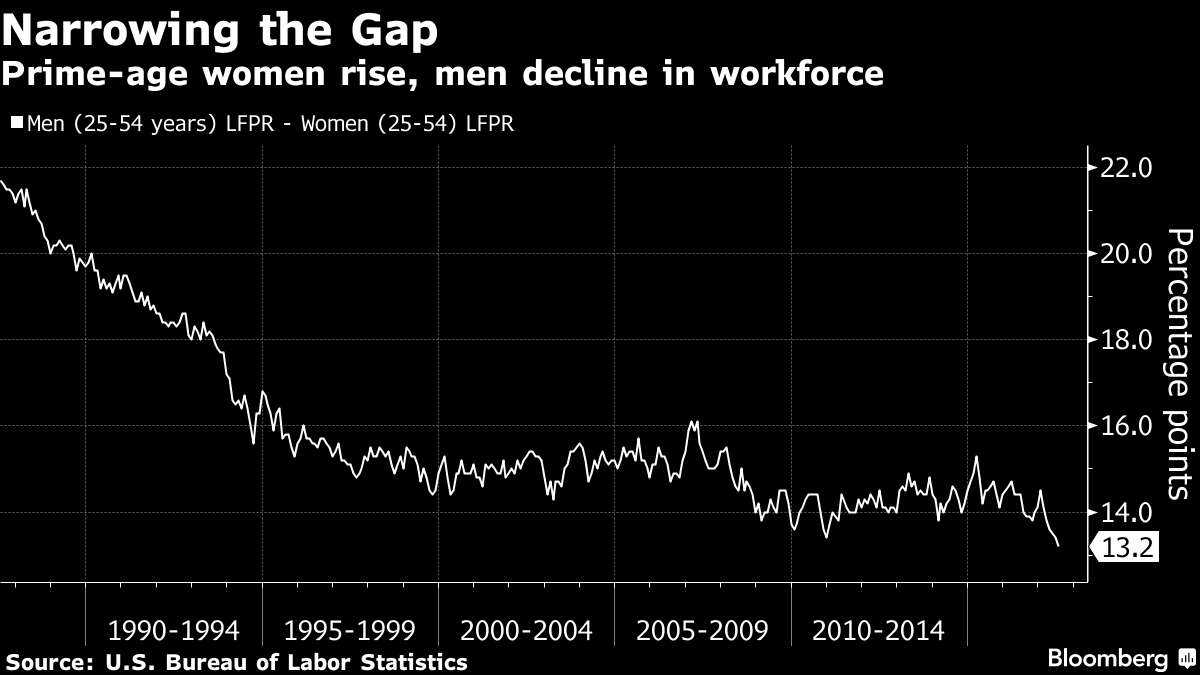

The share of 25- to 54-year-old women either employed or actively looking for a job rose to a seven-year high in July, while the rate among prime-age men merely ticked up for the first time since January, according to Bureau of Labor Statistics data released last week. The 0.3 percentage point increase for females narrowed the gap between the two groups to 13.2 points, the lowest in records to 1948.

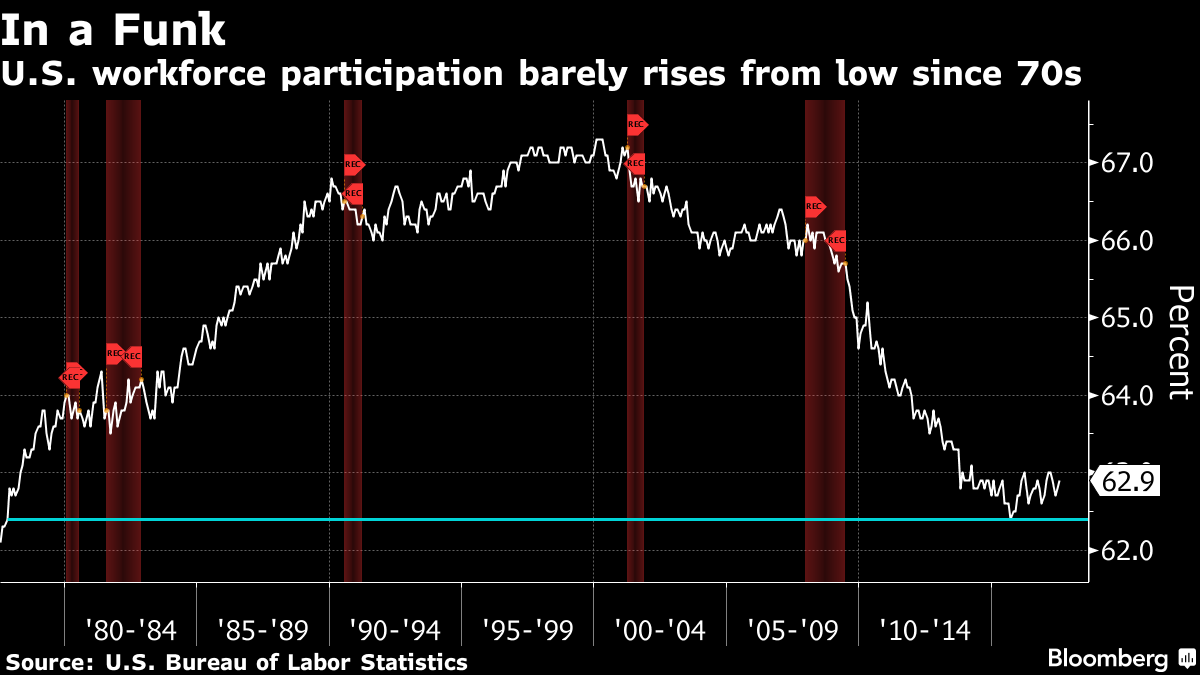

The divergent trends between men and women since the end of 2015 put the nation’s overall participation rate at 62.9 percent last month, close to the lowest since the 1970s.

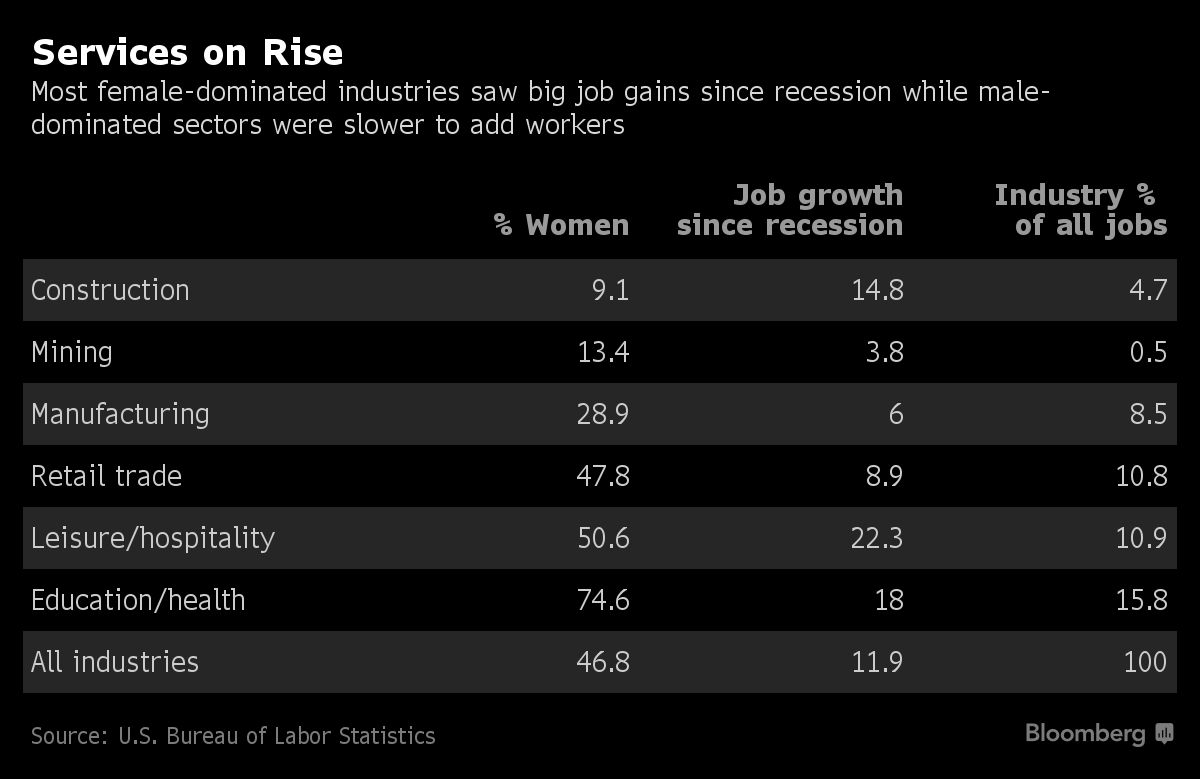

Labor force participation among women, which eased along with the male counterparts in the aftermath of the Great Recession, has been on an uptrend again over the past two years. Younger prime-age women, especially, have been filing into the workforce. That’s coincided with faster-growing job growth in industries traditionally dominated by women such as health care and education.

The declining participation among prime-age male workers has become an area of focus for President Donald Trump’s administration. Trump campaigned on reviving traditionally male-dominated industries such as coal mining and manufacturing that have struggled against greater globalization. Amid record-high job openings, the president has emphasized that Americans need to be open about relocating for work. Mobility has declined to an all-time low in U.S. Census data back to 1948.

As Trump tries to achieve his 3 percent to 4 percent economic growth goal, participation matters because it’s one of a few basic ways to pull the expansion out of a 2 percent rut: more workers and more output per worker. Measures of productivity have been lagging along with participation.

Peter Mueser, an economics professor at the University of Missouri, in Columbia, still sees a lingering need for healing from the last recession, particularly in pockets of the Midwestern state that have weaker-than-average prime-age male participation. The economy’s overall improvement hasn’t coincided with a similar easing in the use of government benefits, including the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, in Missouri, he said.

While more involvement from women has kept the participation rate from falling further, both cyclical and structural factors are limiting progress.

Prohibitive childcare costs make parents’ decision to return to work more difficult, and prime-age Americans are feeling the increased burden of caring for an aging population. The opioid epidemic also helps explain why a portion of the workforce is deemed unemployable. And immigration limits imposed by the Trump administration could curb workforce growth in industries such as farming and construction that are dominated by the foreign-born.

“The aging drag is not going away, which means there needs to be more upside” from recent trends, UBS economists led by Robert Sockin wrote in an Aug. 8 research note. That would include increased participation among younger workers as increases in higher education enrollment stop surging, and a leveling off in the share of Americans with disabilities who are out of the labor force, they wrote.