Much of the shortfall is therefore coming from slower population growth, and not some structural problem. The good thing is that there is no problem; the bad thing is that slower growth doesn’t look solvable absent an increase in population growth.

Population growth likely won’t provide a huge boost

Which brings us back to the initial concern: what does this mean for future growth? The great thing about demographic analysis is that we actually have the answers. All of the people who will move into the 25–54 age group for the next 25 years have already been born.

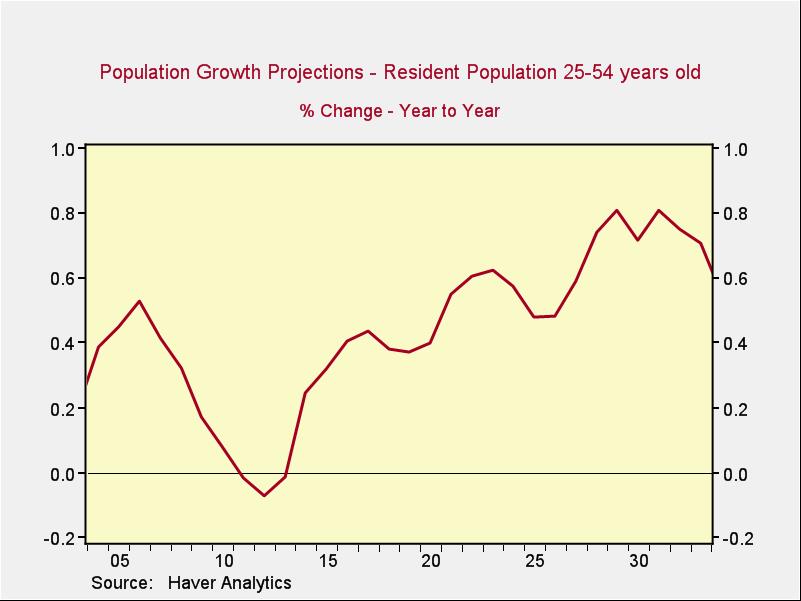

The biggest piece of any demographic change over the next 10 years will be the millennial generation. As you can see from the first chart above, millennials have already started to move into this population cohort in the past three years, with growth resuming after several years of decline. But will that growth continue?

With current population growth in this key cohort around 0.3 percent, the increase to around 0.8 percent over the next 10 years or so will have a material positive effect, but it will only increase the base growth rate from the current 2 percent to 2.5 percent or so up to around 3 percent at best.

This will certainly help, and it will be a tailwind overall, but it won’t get us back to the growth rates everyone is looking for. Less-slow growth is better, but it’s not the same as fast growth.

That’s the not-so-good news. There is, however, better news about why recent growth has been slow, which does offer some possibility for improvement. We’ll talk about that Friday.

Brad McMillan is the chief investment officer at Commonwealth Financial Network, the nation’s largest privately held independent broker/dealer-RIA. He is the primary spokesperson for Commonwealth’s investment divisions. This post originally appeared on The Independent Market Observer, a daily blog authored by McMillan.