Luckily for the future of indexing, at the beginning of 1974, Wellington Management Co. fired its chairman and chief executive officer, John Bogle. Bogle went on to found Vanguard Group and, a year later, convinced Vanguard’s board to launch the First Index Investment Trust, a mutual fund designed to match the performance of the Standard & Poor’s 500-stock index. Fortune called index funds “an idea whose time is coming,” bolstering Bogle’s optimism that Vanguard could raise as much as $150 million in an offering for the new fund.

“It was a complete flop,” Bogle recalled in 2014. The world’s first index mutual fund launched with just $11.3 million.

The critics pounced. “Moving from a fully managed fund to an index fund is merely trading one set of risks for another,” Stanford Calderwood, a consultant, wrote in Financial Analysts Journal in 1977. He warned that index funds could be “self-defeating,” moving stock prices with their automatic buying and attracting “some MIT computer genius” who could “rip off the index funds” by trading against them. To this day, Vanguard takes great pains in trading its trillions of dollars in assets to avoid moving prices or giving other traders an advantage. (Here's how they do it.)

Vanguard initially decided its new fund couldn’t own all 500 stocks in the S&P index. Instead, First Index Investment Trust—later renamed Vanguard 500 Index Fund—owned only the 200 largest stocks in the S&P 500 and 80 smaller stocks chosen as representative of the others.

Samuelson praised the new fund but complained that it came with a load of as much as 6 percent of assets invested, a fee that encouraged brokers to sell the fund to their clients. In 1977, Vanguard eliminated its loads. That only made it harder for it to attract assets to the fund.

Without brokers working hard to sell the fund, investors would come only if there was “some ‘proof of the pudding’ in the fund’s performance,” Bogle said.

The early years were underwhelming. From 1977 to 1979, the fund beat only a quarter of other stock mutual funds, according to Bogle. From 1980 to 1982, it outperformed only half.

Then it started living up to the theory, beating three-quarters of competing mutual funds during the rest of the 1980s. Other firms started experimenting with index funds in the mid-1980s, though they charged higher fees, which dampened their appeal. Vanguard kept lowering its fees and putting out new index funds to capture the returns for small stocks, the total U.S. stock market, international stocks, and the bond market.

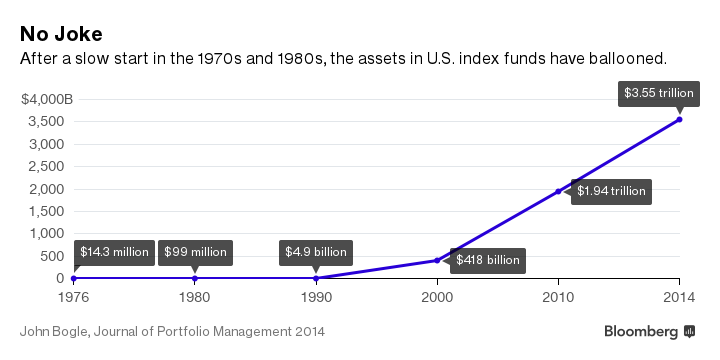

By 1995, Vanguard could declare “the triumph of indexing,” though the product's stellar performance since then shows that the boast was premature. Investors piled into exchange-traded funds, now with about $3 trillion in assets, most of them index-based. PricewaterhouseCoopers predicts that the number could hit $7 trillion in five years. Vanguard’s assets have more than tripled since 2008. The recession and financial crisis caused the popularity of indexing to soar, as the S&P 500's recovery produced gains of more than 200 percent and investors became more and more reluctant to pay fees for active management.

Four decades ago, a financial research firm, Leuthold Group, distributed a poster to clients on Wall Street. "Help Stamp Out Index Funds," it declared, over an image of Uncle Sam. "INDEX FUNDS ARE UNAMERICAN!" Employees of the firm later said it was a joke. Last week, Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. argued that index funds interfere with the most productive allocation of capital. The firm warned that passive investing is "worse than Marxism."