Time has a way of taking the edge off harsh realities. But forgetting how things were can be a very expensive mistake.

Euro Blowback

Greece, not so long ago, was the extreme epitome of Europe’s worst: fiscal mismanagement, inflexible labor markets, soaring joblessness, broken balance sheets—refusal to squarely face reality. And these issues were found hanging over much of the continent’s troubled periphery.

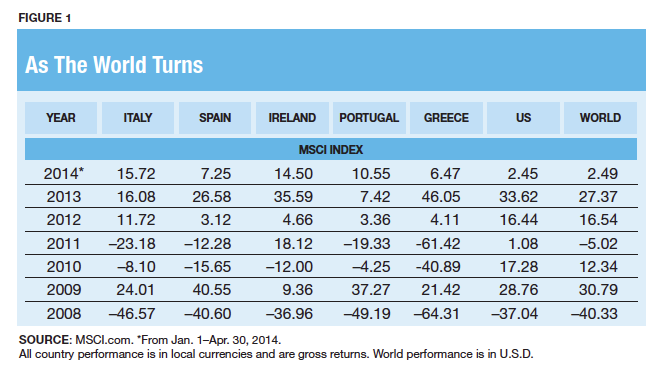

But in 2013, Greek shares soared by more than 46% in local currency terms, according to MSCI. Irish stocks climbed 36.5%, Spanish stocks 26.5%. Portugal and Italy registered modest gains. (See Figure 1.)

The rally was triggered in large part by the pending return to growth. Though Ireland’s three-year recession ended in 2011 with GDP having expanded an average of 1% over the last three years, the other countries in the group known pejoratively as “PIIGS” (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain) were mired in longer economic contraction that cumulatively chopped off economic activity, by 6.20% in Spain and by nearly 23.5% in Greece. The International Monetary Fund now projects growth to return to all the markets in 2014.

Current account balances as a percentage of GDP have also been on the mend, with four of the five countries having posted positive numbers in 2013. The IMF projects Greece’s ratio to turn positive this year.

Collapsing interest rates have also been an encouraging trend. Since early 2012, Greek 10-year sovereign yields fell from 30% to less than 10%, while Portugal’s fell from the mid-teens to 6%. And Italy’s, Ireland’s and Spain’s high-single-digit yields have normalized below 4%.

Private equity flows—a possible read of what smart money is thinking—has been surging back into Southern Europe, according to the data tracker Preqin. Stuck under €500 million from 2010 through 2012, PE surged above €1 billion last year. In late February, venerable hedge fund managers George Soros and John Paulson each invested €92 million in a new Spanish real estate trust—a sector that was at the economic front of the country’s collapse.

And in December, the Purchasing Managers Index—an indicator of future economic performance—broke 50 across each of Southern Europe’s troubled markets, indicating expansion. And in January, the number grew even larger.

So does all this mean the PIIGS are out of the woods?

For short-term investors, the answer is yes. Money has been made and will be made as GDP growth and profitability return on the backs of falling labor costs and increasing domestic competitiveness and as more investors are lured by the prospect of continued revival. “The recovery is real and the worst is behind us,” claims Jing Sun, who manages $136 million in global portfolios for Centre Asset Management.

However, Eric Stein, who manages the $5 billion Eaton Vance Absolute Return Fund, a conservative cash-plus fund, thinks otherwise. His fund has no long euro zone exposure because he thinks ECB policy, rather than fundamental improvements, has been driving the credit and equity rally.

Sun counters by saying there is mounting evidence that serious reforms are paying off. Accordingly, he believes that local governments will have an easier time pushing through additional structural changes, despite the hardships they engender.

That will be the key for longer-term investors. Systemic problems that sent these economies into tailspins are still far from fixed, and they remain vulnerable to poor extant economic conditions and deficiencies of common currency. Understanding the latter requires a look back.

Two decades ago, European leaders had devised standards to determine which nations were responsible enough to join the euro—even though they often closed one if not both eyes in waving suspect nations through admission.

Furthermore, the plan never agreed on a means to effectively deal with—even expel—member economies turned dysfunctional. Making things worse is that when nations stumbled, they no longer could count on a reviving jolt that would come from the subsequent weakening of their currencies. And this change is now a key problem.

Pre-1999, before the euro, currency devaluation was a relief valve for troubled economies. A weakening currency would lower the cost of locally produced products, services and securities to foreigners, even before structural reforms were put in place. Devaluation alone could help jump-start a faltering economy, albeit without necessarily fixing it.

Some may argue that without this relief valve, troubled economies now must effect essential reforms before they see any improvement. This may ultimately lead to a healthier euro zone down the road. But it means that hard times last longer.

With the euro zone lacking a game plan to deal with such difficulties, what investors saw during the banking meltdown of 2010 and 2011 was the European Central Bank and its constituent members making up answers on the fly. Markets generally don’t respond well to such uncertainty. Greek stocks proceeded to lose nearly 80% (in local currency terms) during these two years, according to the global index tracker MSCI.

But it wasn’t just Greece that investors feared. Increasingly indebted government, overextended consumers, rising joblessness, banks socked by overleveraged balance sheets and ownership of local troubled sovereigns and busted housing booms across the euro zone’s periphery revealed a region ripe for contagion as investors started to look more suspiciously at some of Europe’s former tiger economies—especially Spain and Ireland.

More Than Lipstick?

June 2014

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment