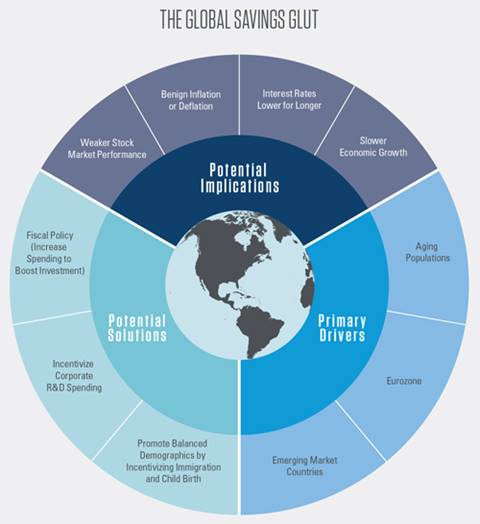

Can savings be a bad thing? Many people think of saving money as a best practice when it comes to managing their finances, but if everyone in an economy (or even just a single saver that controls much of the wealth) saves at the same time, spending is likely to decline, leading to slower near-term economic growth. This concept also applies to countries. When countries save more than they “spend” (e.g., invest), they may actually cause problems related to slower growth, including downward pressure on interest rates, deflation, and weaker stock market performance. Economists who believe we’re in the middle of a “global savings glut” think that’s exactly what’s happened in recent years. Figure 1 shows some of the potential implications of a global savings glut, which will be discussed in more detail later.

What is a Savings Glut?

The global savings glut hypothesis, which was popularized by Former Federal Reserve Chair Ben Bernanke more than 10 years ago, states (in basic terms) that the world is dealing with an excess of savings, and, as a consequence, insufficient investment. The theory is controversial and competing theories exist, but it does help to explain some of the issues faced by the world economy in recent years.

The negative impact of saving too much makes more sense when considered from an economic perspective. Spending, whether from consumers, businesses, or governments, ultimately drives economic growth. The major benefit of saving from an economic perspective is that it allows us to push spending forward, whether we’re “saving up” for something or planning for a time when our income levels might decline, such as retirement. Thus, although we may need to build up our savings initially, the ideal outcome for continued growth is for those savings to lead to increased spending in the future. LPL_HD:Users:llennon:Desktop:TL 5460 0416:charts:png:TL-Global-Savings-Glut_04262016_info.png

One way a country’s “savings” can be measured is through its current account balance, which economists think of as the amount a country saves minus what it invests domestically. This difference is reflected in trade relationships, which is another way of looking at the significance of the current account balance. A country with a trade surplus is exporting more than it imports, or saving more than it invests back into its country. Just as a consumer spending less and saving more will result in slower economic growth today, the same is true for any individual country.

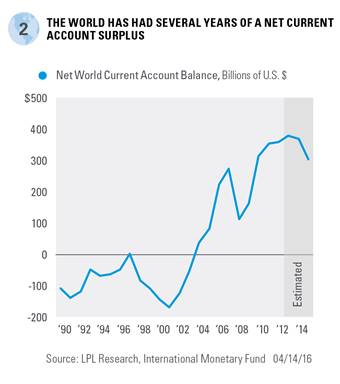

How a country disposes of its savings also matters. Over time, the total of all of the individual current account surpluses and deficits in the world should net out to zero, meaning if one country “borrows” through a current account deficit, another country will “lend” from its surplus. But over the short term, the numbers don’t always net out; because just like a consumer can have a savings account, a country can place its savings in reserve. In fact, this is what has happened in recent years, leading to a net current account surplus for the world [Figure 2].

Drivers of the global savings glut

The primary drivers of the global savings glut originate in both emerging market (EM) and developed countries, with several contributing factors, such as a need to reduce debt, low demand for investment, aging populations, and the large amount of cash held by corporations.

EM Countries: Historically Big Savers

EM countries, led by China, were historically big savers and ran large current account surpluses over time. In response to the late 1990s Asian financial crisis, EM countries set out to reduce debt and increase savings. EM countries also tend to have higher savings rates than developed nations, given weaker social safety nets. Additionally, the commodities boom of the 2000s boosted revenue for many EM countries, especially heavy commodity exporters in the Middle East.