Every quarter the same scene plays out as investors review portfolio performance at meetings across the country: a discussion on whether or not to terminate an investment manager, borne from frustration following several quarters of below-benchmark performance. These discussions are a call to action, and often prompted by a desire to replace the underperforming manager with another money manager who has performed better in the recent past. Inevitably, the temptation is to make a change from the underperforming manager to the one who has recently outperformed.

We would all like to think that the best and brightest of the investment world would be able to consistently beat their benchmarks year after year. In fact, we want to know that they have the knowledge and ability to do so without fail. Unfortunately this is just not the case. Even those managers that outpace their benchmarks for extended periods of time inevitably suffer missteps. Take Legg Mason's Bill Miller, for example. As of 2007, he had outperformed his benchmark, the S&P 500, for the previous 15 consecutive years. Unfortunately, he gave back most of his gains in the four years that followed.

The truth is that consistent outperformance year in and year out is more of a myth than a reality. Even "good" money managers will have periods of underperformance, as long-term outperformance is nearly always made up of both good and bad periods. The question becomes: Will the investor be patient enough to stay with the manager through these periods and reap the potential longer-term rewards?

Periods Of Underperformance

If a manager is having a lull, it will show up in the periodic performance numbers. For example, the one-, three-, five- and even ten-year returns will lag the benchmark. It is important to realize that these statistics represent only single snapshots in time. As a result, recent underperformance can affect the periodic returns dramatically. More often than not, these relative returns can and will change direction from quarter to quarter. In many cases, we see the poor performance turn positive in less than four quarters if the manager begins to perform well.

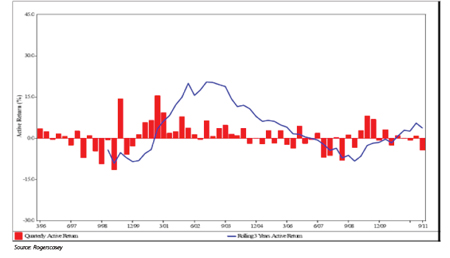

Now, of course there are many statistics used to evaluate a manager's performance, such as Sharpe ratios and information ratios as well as numerous others. However, one very telling and appropriate way to assess long-term performance is to examine rolling three-year periods. These results show a manager's three-year performance over multiple consecutive periods and demonstrate how consistently the manager has performed. For example, the following chart shows that a sample manager has outperformed the previous three-year period almost 60% of the time, with two prolonged periods of underperformance. In the long run, this manager has also outperformed its benchmark.

Figure 1 - Sample Manager Performance Over Rolling 3-Year Periods

Looking at the three-year rolling results of top quartile managers in the large-cap core universe is instructive; 86% of these top performing managers underperformed the universe median return in at least one rolling three-year period when measured on a quarterly basis. That means that an overwhelmingly large number of the top-performing managers inevitably suffered a three-year period where they lagged their index. You can imagine the discussions that must have taken place at the quarterly meetings of investors in these strategies. However, if an investor had voted to terminate on recent performance alone, he would not have reaped the benefits of those managers once again recovering.

Locking In Underperformance

Many investors have been conditioned to terminate investment managers when they underperform. It is very important to realize that when a manager is terminated during a period of underperformance, not only will the negative performance be "locked in," but there is also no chance of the investor reaping the benefits of that manager when he or she regains its edge. Now, think of what happens to the total portfolio return when managers are constantly terminated at the bottom of their cycle. Given a pattern of terminating underperforming managers, the result is the continuous realization of underperformance in every asset class, making it nearly impossible for the investor's portfolio to outperform in the longer term.

On the flipside, investors also tend to hire managers who have recently performed well. These managers are often in the sweet spot of their cycles and may very well be the next to suffer underperformance. Added to the "terminating at the bottom" behavior, this can be a double whammy for a portfolio.

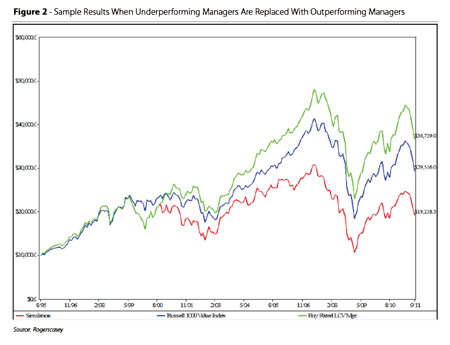

The following graph is a very simple example meant only to demonstrate what could happen when an underperforming manager is terminated and an outperforming manager is hired in his or her place. The three managers selected are Rogerscasey buy-rated large-cap value managers, and the simulated returns reflect a period during which the lagging manager was replaced with the outperforming manager. While this example is just a model and most likely would not happen to this degree in practicality, it shows that by continuously locking in the underperformance, even when using buy-rated managers, the portfolio can dramatically underperform both the benchmark and more important, the original buy-rated manager in the long run.

The Cost Of Transition

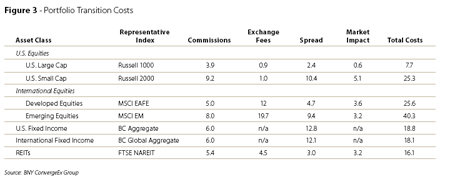

Many investors forget that there are costs associated with transitioning a manager. In most cases, securities will have to be both bought and sold, subjecting the portfolio not only to commissionable transactions, but to intraday market volatility as well. The data in Figure 3 shows the breakdown of costs, in basis points, that a portfolio might incur. All costs are based on a $50 million liquidation of an index-like portfolio. On average, the total cost to liquidate a portfolio of this size is approximately 20 bps, or $100,000. As one would expect, the highest liquidation costs are associated with foreign-based equities and small cap stocks. In addition, the total cost of transitioning can be even greater, depending on the amount of out-of-benchmark securities the portfolio contains. Added to all of this is the likelihood that another manager is being brought in to replace the one being liquidated, so the costs will be incurred on both the liquidation and the retention of the new manager.

So, When Should One Terminate?

We are certainly not advising our clients to retain all underperforming managers. We are just trying to bring light to the fact that a termination decision is often made out of frustration that the manager has lagged its benchmark, and not based on research and forward-looking expectations. Central to the discussion is the quality of the manager and whether or not it can recover. This is where the ratings and research of one's consultant come into play. It is the job of the consultant to remove emotion from the decision and to present the facts as to why the managers may or may not outperform once again.

Conclusion

Clearly one should not blindly retain all underperforming managers. Recent performance, however, should be only one of a number of criteria used to determine when to hire or fire a manager. At Rogerscasey, we advise clients to make all of their hiring and firing decisions based on a diverse set of qualitative and quantitative factors with an eye on prospects for future performance.

Dave O'Donovan is a managing director, Jason Bailin, CFA, is a director and Nick Catanese is an associate at Rogerscasey, a global investment solutions firm serving institutional asset owners and financial services firms for more than 40 years. Learn more at www.rogerscasey.com.