The conundrum faced by Alan Greenspan is back -- and possibly worse. This time, the Federal Reserve is confronting a “far more dangerous” backdrop in the bond market as it gears up to further raise interest rates.

The prevailing dynamics in the Treasury market -- an ever-narrowing gap between short and longer-term U.S. Treasury yields, and record lows in forward rates for this point in the monetary cycle -- could derail the Fed’s tightening path, according to Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

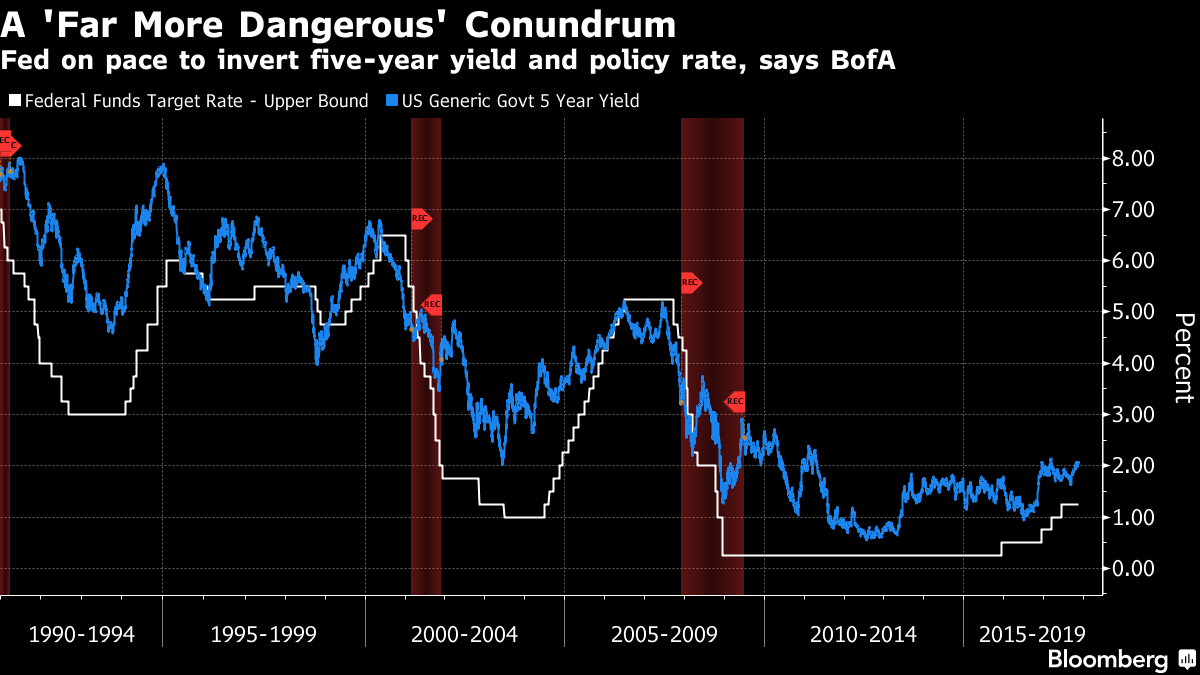

Though a flattening yield curve is seemingly a replay of previous rate-hike regimes -- including the one overseen by Greenspan and Ben Bernanke, which culminated in the financial crisis -- Bank of America sees extra cause for concern. A Fed that’s intent on raising rates four to five more times by the end of 2018 would risk “consciously putting short-term rates above five-year term rates,” strategists led by Shyam Rajan wrote in a report Wednesday. That’s something the central bank has never allowed to happen aside from a brief period in the last month of its 2004-2006 tightening cycle.

If the central bank aims to avoid such an outcome, it would imperil what’s been one of the hottest trades in 2017: betting that the flattening curve will endure. Bank of America is reiterating its call that the intermediate portion of the Treasury curve -- two- and five-year note yields -- will steepen as the Fed seeks to ensure that rates hikes are accompanied by higher expectations for inflation and where the policy rate will eventually end up.

According to BofA, the drop in long-term market-based inflation expectations, as shown by 10-year, 10-year forward rates, should worry Fed Chair Janet Yellen and her designated successor, Jerome Powell. Back in 2005, expectations for longer-term rates were falling even as Fed funds rose, a phenomenon Bernanke attributed to a global savings glut.

“Today, if they are trying to take a message from the yield curve, it is that long-term rates are low because of market disbelief in their ability to hit the long-run inflation target,” Rajan said.

A drop in inflation expectations could risk sparking something of an existential crisis at the Fed by permanently limiting policy makers’ capacity to provide monetary stimulus. As it stands, the low level of long-term rates -- with the 30-year note yielding a paltry 2.79 percent -- implies the central bank has less ability to offer an economic boost by exerting downward pressure further out on the Treasury curve at this juncture.

“The Fed would like to see an upward shift in the yield curve, with it not flattening as quickly as it has been,” said Tim Duy, senior director of the Oregon Economic Forum at the University of Oregon. “If they want that, what they would want to do is to sit back and not raise rates now and let the long end rise in response to higher inflation expectations because they’re not reacting as as aggressively.”

The five-year yields suggest market participants continue to doubt the long-run policy rate will actually reach the 2.75 percent depicted in the Fed’s so-called dot plot forecast, Duy added, so raising that estimate wouldn’t help foster any steepening in the curve, he said.