Global aftershocks

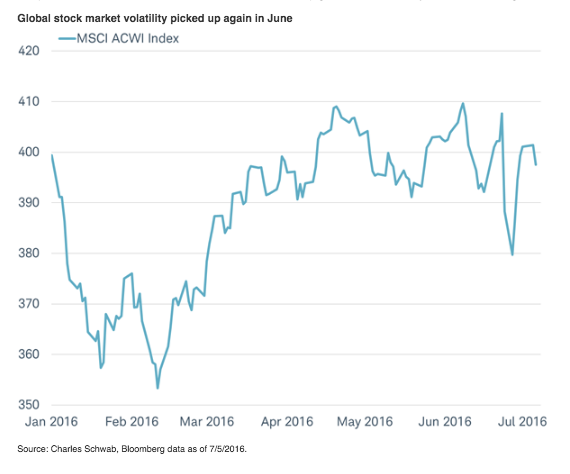

Global markets continue to focus on the U.K.. Following the Brexit vote on June 23, global stocks saw a sharp 7% two-day decline followed by a rebound which was nearly as dramatic. There are more questions than answers with regard to Europe’s economic and political outlook, which could lead to aftershocks and keep global market volatility elevated in coming months.

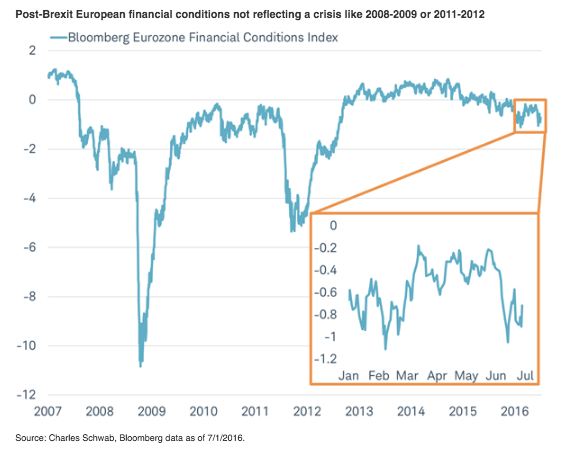

International markets also steadied after the initial Brexit vote shock, as the U.K.’s standing in the EU doesn’t change right away, and the financial system hasn’t shown the level of stress seen in past crises. In fact, financial conditions—a key real-time indicator of the risk of a global recession—showed only a slight deterioration in June. The Bloomberg Eurozone Financial Conditions Index—which quickly signaled oncoming recessions and bear markets in both the financial crisis of 2008-2009 and debt crisis of 2011-2012—is not showing anywhere near the sharp deterioration seen in those periods, as you can see in the chart below.

Post-Brexit European financial conditions not reflecting a crisis like 2008-2009 or 2011-2012

The Bloomberg Eurozone Financial Conditions Index tracks the overall level of financial stress in Euro area money, bond, and equity markets to help assess the availability and cost of credit. A positive value indicates accommodative financial conditions, while a negative value indicates tighter financial conditions relative to pre-crisis norms.

We are also watching other real-time indicators of potential contagion and crises stemming from Brexit, including:

Market volatility is likely to remain elevated in the coming months due to economic and political uncertainties. The first indications of the Brexit economic impact will be in the July data, released beginning in late July and through August. It will not be surprising to see some deterioration in initial economic releases, although it may take several months before the extent and duration of the impact is more certain.

Outside of U.K. politics, the Italian constitutional reform referendum in October, where Prime Minister Matteo Renzi could step down if he is unsuccessful, is the next political risk ahead of U.S. elections.

In the meantime, nothing is likely to happen quickly. There are a series of steps before we can fully assess the political path forward in the U.K., whether Scotland will have another referendum on U.K. membership, and the future of Ireland’s borders. Presently, the path seems to start with the U.K. selecting a new Prime Minister in September 2016; then Parliament must vote and inform the EU of the intention to leave per Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty probably no earlier than the fourth quarter of 2016; then negotiations may begin in earnest in 2017 and could last through late 2018, or longer if extended. Until the negotiations are complete, there are no material mandated changes in the way companies do business in Europe. What we do expect is a long drawn out negotiation process as the most likely outcome. This may mean either lingering uncertainty weighs on economic activity or that it mostly stays in the background until material developments take place over the course of the coming years.

International allocations as part of a diversified portfolio can help minimize the impact of global shocks. Despite the swings in markets over Brexit, the performance of global stocks, measured by the MSCI All Country World Index (ACWI) and the S&P 500 Index differed by less than a percentage point for the month of June. Emerging market (EM) stocks actually posted gains for the month of June, outperforming the S&P 500 by over three percentage points. Even more importantly, global diversification has paid off historically over the long-term, when it was needed most. The worst 10-year period for the stock markets over the past 50 years was from February 1999 to February of 2009—a period that included both the tech and housing bubble aftermath. During that period, the U.S. S&P 500 Index fell about 40% while international stocks (MSCI EAFE Index) fell only about 10%. That’s a big difference that favors maintaining global portfolio exposure over the long-term even when times are difficult.

So what?

With Brexit uncertainty likely to remain for the foreseeable future, investors should be prepared for increased volatility, but take opportunities to rebalance around longer-term strategic allocations. At this point, we don’t see a major U.S. economic impact from Brexit, and we remain neutral on U.S. and global equities, expecting a modest upward trend with bumps along the way.

Schwab Market Perspective: Looking Beyond Britain

July 11, 2016

Liz Ann Sonders is senior vice president and chief investment strategist at Charles Schwab & Co.

Brad Sorensen is managing director of market and sector analysis at the Schwab Center for Financial Research.

Jeffrey Kleintop is senior vice president and chief global investment strategist at Charles Schwab & Co.

« Previous Article

| Next Article »

Login in order to post a comment