It’s hard except with hindsight to remember the evolution of an industry or profession. There was a time when clockmakers were independent artisans cutting their own gears by hand near a river, until the advent of mass production allowed clock production with replaceable parts to coalesce in Connecticut around the 1820s. Or think of how the internet remade the travel industry, ironing out the inefficiencies of booking airfare and hotel rooms with real time numbers and washing out a third of U.S. travel agents in two decades.

Now think of the RIA business—one still young enough to feel growing pains (such as its struggles with HR departments) but old enough for some to now imagine it having its own variant of the accounting industry’s Big Eight (before they shrank into the Big Four).

To view FA's 2023 RIA Ranking, the list of the 50 Fastest Growing RIAs and all of the participating firm’s Discretionary and Non-Discretionary AUM, click here.

Then there’s the messy, still fragmented present. The frenzied consolidation of financial advisory firms, predicted for two decades, has finally slowed down as financing becomes more expensive. That will likely bring down firms’ lofty valuations, which recently stood north of 10 or even 12 times cash flow.

Stephen Galletto, an attorney at Stark & Stark who helps sellers, says that even before Covid-19 he saw small RIAs having “stupid money” shoved in their faces from aggregators wanting to acquire clients and assets (and the rich, recurring revenue streams), even if the advisor didn’t want out of the business. According to some estimates, the global private equity industry currently sits on $1 trillion in capital and it earns nothing unless that money is put to work.

Attractive recurring RIA revenue streams have lured new giant, target-hungry acquirers. Marty Bicknell, who runs his own giant shop, Mariner Wealth Advisors, says new players have emerged that nobody would have seen coming four years ago—firms with $20 billion to $40 billion in assets that have pounced on the space, aided by cheap financing and easy access to capital. And yet, as big as some firms are getting (he hopes to get his own shop up from 1,400 to 5,000 advisors in three years), he notes that the wirehouses employ tens of thousands of advisors. LPL Financial has more than 21,000. In other words, the increasingly popular RIA model still faces other big models like private banks and brokerages.

Yet it’s also hard to imagine the complete consolidation of RIA firms when so many new practices are starting up all the time. Will the profession fall into fewer powerful hands like accounting did or will it continue to look like the medical profession, with both HMOs and small group practices flourishing, with the latter offering the kind of high-touch service necessary in a business where client relationships are sticky and precious—and hard to replicate by a big corporation?

“There’s thousands and thousands of advisors out there; there’s more RIAs that are being created each year than are getting acquired,” says Dave Welling, the CEO of Mercer Advisors, which oversaw $48 billion as of April.

Matthew Brinker, a managing partner with Merchant Investment Management, an investment company that makes minority investments in firms, says all the borrowing with cheap money has finally caught up to the private equity buyers. Acquirers that paid for firms at the top of the market are likely to see their revenue buffeted now that stocks have stopped rising—and as debt gets more expensive. He compares the current situation in private equity to that of the 2008 financial crisis, when highly levered acquirers took on a ton of debt to pay at the top end of multiple ranges for firms across an array of industries—and then struggled to restructure finances as major banks wrestled with the mortgage crisis.

Brinker hesitates to name names, but a few big firms have recently come in for criticism for their high debt leverage numbers and their strategies to fix them, namely Focus Financial and CI Financial’s U.S. wealth management business. Both serial acquirers own some of the best big RIAs in the business. They also have lots of company when it comes to carrying big debt loads.

Focus and CI recently turned once again to private equity, this time to restructure their debt. CI not only nixed plans to go public this year but instead sold 20% of itself to a consortium led by Bain Capital, bringing in a billion dollars in an aggressive move to deleverage. Focus, meanwhile, took itself out of the public market altogether with the help of private equity firm Clayton, Dubilier & Rice—and got its ratings slashed by Moody’s and Standard & Poor’s as a result.

CI Financial’s deal drew initial market applause for its rich valuation but was later slammed by analysts who said the deal terms with Bain were more constraining than at first assumed. The Toronto-based consolidator was forced to pay 14.5% in pay-in-kind convertible debt over six years to guarantee its return to the Bain investors. A CI investor relationship specialist spoke with Financial Advisor and said that the RIA business has in fact been growing faster than its debt, theoretically protecting equity in the mother ship. He declared there are no guarantees to the debt holders that would hurt the parent company itself, CI, or its stockholders, but 14.5% is more than 10% above 10-year Treasurys.

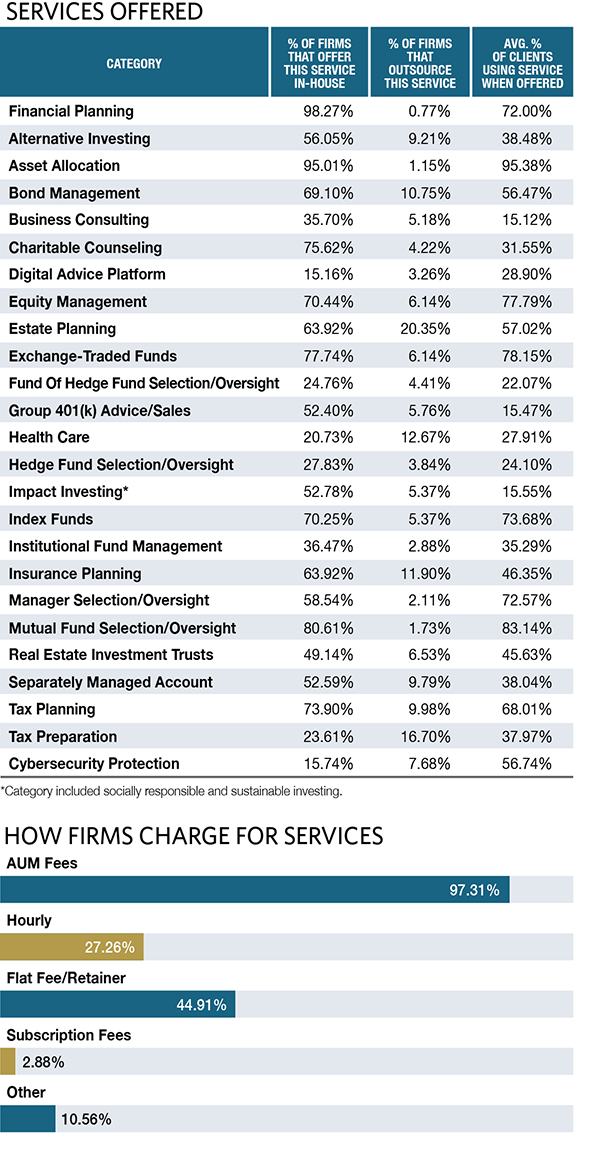

Many CEOs agree that private equity is more patient capital and understands the RIA space better than public markets, but critics say the race to leverage individual firms and gobble them up shows the worst of the aggregator model. Simply trying to arbitrage EBITDA multiples (assigning a high multiple to a large entity and using the stock as currency to buy many smaller firms at lower cash-flow multiples) without integrating the businesses creates a less-than-ideal model. Indeed, many of today’s acquisition vehicles like Mercer and Creative Planning portray themselves as integrators, not aggregators, and are adding dozens of professionals in areas like tax planning and estate planning to build out client relationships beyond basic asset management services.

David DeVoe, founder of investment bank DeVoe & Co., says Focus likely went private because its valuation as a public company seemed to be at a discount to what private companies were paying. He adds that public investors are less comfortable with higher debt ratios. In a private equity setting, the ratio of debt service to cash can max out at 7 times, “but the public markets expect to be closer to 4 and a half or so.” (Focus said its net leverage ratio in March was 4.41x, and said it was committed to being in the 3.5x to 4.5x range.)

“So by going private,” DeVoe continues, “you actually create space to bring on additional debt that would have been constrained as a publicly held firm. So [Focus] was arguably undervalued and by taking it private they had more access to capital for acquisitions.”

DeVoe continues that private equity firms had already anticipated some of the interest rate increases and modeled that into their original purchase prices, but says rates then rose further than anyone imagined. “When you run a large organization, you have to be sensitive to how much debt you take on and what your debt service is.”

In a way, these firms are trying to get over the hump: If the stock markets rebound, these bets will have likely paid off. But before the S&P 500 swooned in 2022, the frothy markets also allowed a lot of bad behavior and papered over organic growth that everybody thinks was unimpressive.

“When the markets were strong, markets were able to bail firms out,” says Jason Ozur, the CEO of Lido Advisors in Los Angeles. “When you take a firm that has $5 million in EBITDA, I’m sure some of the large aggregators last year in ’22 were paying 12 times EBITDA. So that’s a $60 million purchase price. Now in order to pay for the $60 million, what do they do? They draw down on their debt. So $60 million of debt is going to cost most firms about $6 million in interest expense. Fast-forward to the end of 2022: The stock market went down, bonds went down.” Meanwhile, he says, a firm’s EBITDA might have dropped down to $4 million. “Now you have $6 million of carrying costs for $4 million of EBITDA. So you’re starting to see a lot of firms who are over-levered and have a need to go out and raise additional capital or [preferred] equity.”

According to Brinker, aggregators work under a “shot clock” mentality. Because the capital on their books is so expensive, these deals have to get done, he says, even if the terms are a moving target that’s likely to change. For instance, if a firm’s management sold a guaranteed EBITDA stream to a financial backer, in the worst case scenario that could squeeze out the managers’ take entirely if cash flow falls low enough. Those managers would either demand new terms or quit.

“Again, people that are buyers on the merits of the quality of their platform,” Brinker argues, “they don’t have guns to their head.”

Laura Delaney, the vice president of practice management and consulting at Fidelity Investments, says there has been a shift in deal structures. “When money was cheap and there [were] a lot of deals happening at fast cadence we heard many deal structures were 80% cash and equity up front followed by a 20% deferred payment over two to three years. We’re seeing that shift where it’s de-risking on the buy side. It’s more favoring the buyer where it’s more like 65% up front or 60% up-front cash and equity.”

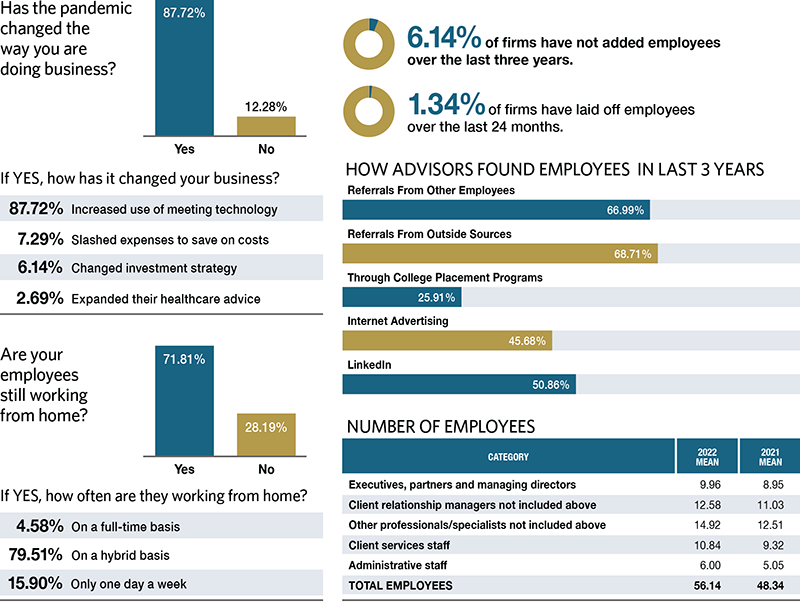

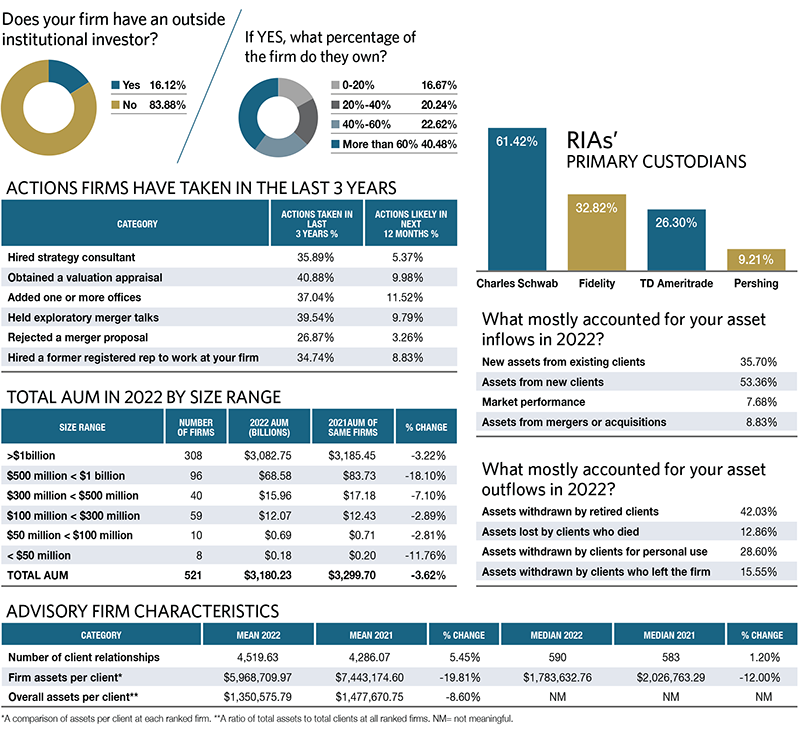

Valuations of RIA firms have remained robust for the time being, say several M&A specialists, because there are other factors at play besides revenue. Dan Seivert, the CEO of investment bank Echelon Partners, says that as RIA revenues are blunted by market forces, a firm’s characteristics become more crucial. The average (based on the mean) firm in Financial Advisor’s 2023 survey saw a 5.45% increase in client relationships and a 19.81% decline in assets under management. The median number of clients rose a more modest 1.2% and median AUM fell 12%. Individual firms’ performance varied widely as some continued to grow through acquisitions and others via robust 401(k) businesses.

“As cash gets more expensive, buyers may find it necessary to extend beyond monetary offers to owners, potentially incorporating equity for younger advisors as an enticing incentive for them to remain,” Seivert says. “On average, wealth managers have less AUM than they did a year ago, which is typically accompanied with stagnant EBITDA growth. However, valuations continue to be robust due to factors such as the aging demographic of financial advisors, the need for scale to invest in technology, regulatory pressures, fragmentation and buyer interest.”

How Does Your Garden Grow?

Seivert says that the most attractive targets are those firms growing organically regardless of investment results. “There is a high demand for achieving economies of scale by improving technology, enhancing back and middle office support, and pursuing vertical integration, particularly in the insurance and wealth services sectors. There has also been a consistent rise in the demand for [turnkey asset management], digital solutions, wealth tech products, and similar technological advances being leveraged to significantly expand a buyer’s suite of offerings to clients.”

There’s more than one way to skin a cat, and more than one way to build an RIA. As firms become larger, there’s going to be more pressure to do more things for more clients —to do estate planning, tax planning, accounting. Many smaller firms that don’t have those capabilities are selling out to larger firms who can.

Brent Brodeski of Savant Wealth Management in Rockford, Ill., says his firm is one of the larger ones not afraid to mix the accounting and advisory businesses. He says other firms are squeamish about that given accounting’s different culture and margins.

“There’s a lot of people that would love to buy the wealth firms out of accounting firms, but nobody’s open to buying the whole package other than us, to my knowledge,” Brodeski says. “By midyear we’ll [be] at $15 million to $20 million accounting and tax revenue. But that’s like 10% of our revenue. And it’s really serving the mother ship—the wealth management business.”

One of the challenges in the current high interest rate environment is attracting talent to grow the businesses. Bicknell at Mariner Wealth says paying good talent is getting harder and harder. That sentiment is echoed by Deb Wetherby, the managing partner of Wetherby Asset Management of San Francisco, which merged with Seattle-based Laird Norton Wealth Management to create a West Coast powerhouse last year.

Wetherby says her firm did a midyear compensation study and felt that mid-level people with four to seven years under their belt were most in demand and not getting paid well enough. “That’s what we found from doing the salary survey, and so we made adjustments. … It feels to me like there is the most competition for mid-level people,” she says, “because those people really add a lot of value.” She describes this cohort as wealth managers in training who are supporting the senior people, “whether it’s running financial projections or researching issues or preparing meeting decks.”

These are also going to be the people necessary to make a firm valuable to acquirers, who want to keep talent and keep it aligned for future years. Advisors are also dealing with asset outflows from clients retiring. Forty-two percent of advisors in this year’s Financial Advisor RIA survey said that assets withdrawn by retired clients accounted for their largest outflows and clients who died represented another 12.9% of outflows.

Despite the challenges advisors faced in 2022, many firm chiefs added that, in the end, they always gain during market turmoil, because that’s the time clients are susceptible to overtures from new counsel. Fifty-three percent of those RIA firms surveyed in Financial Advisor’s most recent survey said that assets from new clients accounted for most of their 2022 inflows, with 36% citing assets from existing clients. It could be that turmoil in other sectors (think of the recent regional banking and commercial real estate crisis) have once again shown potential clients that their funds might be safer in RIA relationships.

Ask David Hou of Evoke Advisors. His team fortuitously left two giant financial firms on the brink of cataclysm—they left Merrill Lynch in 2008 to form Luminous Capital, which they then sold to First Republic Bank. By the time First Republic was liquidated in 2023 after its own collapse, Hou’s team had already moved on and created Evoke in 2019—largely, Hou says, because his team’s alternative assets were easier to manage in a smaller context.

Hou says that banks’ aggressive move into wealth management will not likely threaten RIA growth. “I think people are saying, ‘Do I want to be at a bank that is 20 times levered as opposed to being at a custodian who is much more stable financially?’ … We tended to grow more quickly when the markets were volatile.”