- International investing is currently quite attractive.

- A global trade war benefits no one.

- High tariffs rarely achieve their aim (even if it’s a commendable one).

The global markets are valuable diversifiers that support longer-term stability in returns. Foreign markets also represent roughly half of the world’s market capitalization and about three-fourths of the world’s GDP, which is not the type of growth investors want to miss out on.

Currently, international investing happens to be especially attractive as international market valuations are trading at a significant discount relative to the U.S. market, given strong U.S. outperformance since the 2008 financial crisis. But, it’s important to remember that markets are cyclical in nature and performance leaders change frequently.

Recently, international markets (particularly emerging markets) have been viewed with some concern as President Donald Trump has advocated imposing tariffs on imports to help protect U.S. industries and create jobs — initial discussions have focused on a 35 percent tariff on all Mexican imports and 45 percent on all Chinese imports.

As discussed later, we don’t have to look too far back in history to find examples of similar trade policies that did not turn out well. Reviewing the past, as well as the potential impacts of such policies on the U.S. and other countries shows imposing tariffs could be detrimental to all countries involved, and particularly to U.S. consumers.

What Does It All Mean?

Steep import tariffs could directly impact U.S. consumers. For example, a consumer is interested in a Chinese-made pair of shoes which used to cost $100. After a 45 percent tariff is imposed, the price to the consumer goes up to $145. This could, in theory, encourage the consumer to purchase cheaper, U.S.-made shoes, thus boosting U.S. shoe manufacturing, creating more jobs, growing the U.S. economy, etc. But, there are three big problems with this seemingly simple story:

1) China will most likely retaliate by imposing tariffs on imports of U.S. products (hurting U.S. exporters), and a back-and-forth trade war could ensue.

2) Many U.S.-made products utilize components made in China (such as iPhones), thus increasing input costs for those companies.

3) Other countries that have struggled to compete on price with scale-efficient China and close-proximity Mexico will now get their chance to be major exporters to the U.S. In other words, problem not solved. There will need to be more tariffs on more countries, ultimately resulting in higher prices for all.

One might ask, can a president even impose such policies on his own? The simple answer is no. In order to impose large tariffs and/or alter trade agreements, Congressional approval is needed, making it a more difficult task.

While the President’s intentions to help the U.S. economy and American workers may be commendable, raising tariffs on major trade partners may not be the best way to go about it.

Who is Affected and How?

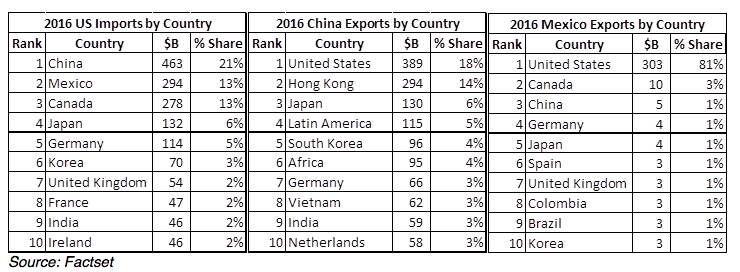

The brunt of the initial impact would be felt by Mexico, China, and the U.S. But, the United States and China are the world’s largest economies, so a trade war between the two could have a larger global ripple effect. The chart below illustrates how much the U.S. currently imports from each country.

These tariffs would have a meaningful impact on the two emerging markets, particularly Mexico as such a large portion of its exports are directed to the U.S. However, a significant amount of U.S. exports is directed to these two markets too.

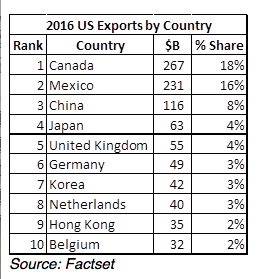

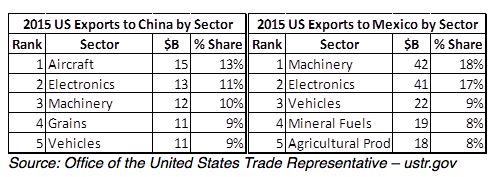

Since both Mexico and China export more to the United States than they import (about four to one for China), the tariffs would have a larger effect on them even after a retaliatory tariff raise of their own. China and Mexico are two of the top three importers of U.S. goods, so any trade disputes would also impact the U.S. Which U.S. industries would be affected most?

American airplane manufacturers, farmers, and automakers (including corporate giants such as Boeing and Ford) would feel the most pain. Simply put, avoiding a trade war and maintaining a healthy relationship with our major trading partners may be the best course of action.

Kostya Etus is portfolio manager at CLS Investments.

Learning from History

A review of history allows us to learn from our successes and, more importantly, our mistakes. But first, let’s review some basic economics. Free trade between countries has been proven to drive growth as it promotes more trade (this is about the only thing all economists can actually agree on). The Eurozone and its prosperity since forming can greatly be attributed to interdependent trade agreements. The North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) between Mexico, the U.S., and Canada has strengthened growth for all three countries since its start in 1994. This agreement would have to be ripped up if tariffs on Mexico were imposed.

Has an isolationist-style, international trade policy been implemented before? There have been two similar policy implementations in the United States. In the late 1920s, desperate to claw its way out of the Great Depression, the U.S. government decided to battle economic weakness by raising tariffs on imports to levels more than 60 percent. This resulted in a global trade war and trading partners retaliated with tariffs of their own. Global trade fell sharply, and the U.S. sank deeper into depression.

The second time was a little more recent. In 2009, the Obama administration noted that tire imports from China were rapidly increasing, and it was becoming difficult for U.S. manufacturers to compete. President Obama implemented a three-year, 35 percent import tariff on all new tires. Over that time, only about 1,200 jobs were created in the U.S. tire manufacturing industry, but consumers spent over $1 billion more on tires than they would have without the tariff. To top things off, China raised a retaliatory tariff on poultry of over 50 percent, reducing U.S. exports by $1 billion in that industry (a 90 percent reduction in poultry exports to China). By far, a net negative for both countries.

In conclusion, imposing tariffs on some of our major trading partners will be detrimental to all parties involved, including the United States, and will most likely not come to fruition. There is too much reliance between countries in our growing global economy and the only way it will continue to flourish is if international trade is made easier, not harder. Investing internationally has been, and will continue to be, a source of growth and diversification for portfolios, and it currently happens to be a great value too.