KEY TAKEAWAYS

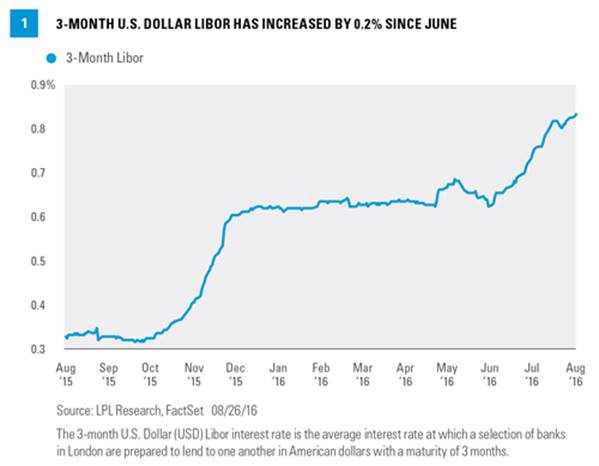

• 3-month U.S. dollar Libor has increased by 0.2% over the past two months, which carries almost the same impact as a full rate hike, even though the Fed has not raised rates since December 2015.

• Investors in bank loans may benefit if Libor continues to rise, given that the floating rates may start to move higher once the 1% Libor floor that many issues carry is exceeded.

• Major drivers of the increase in Libor include money market reform, regulation-driven Libor calculation changes, demand for U.S. dollars in foreign exchange markets, and an assist from Fed rate hike expectations.

Libor has been on the rise in recent weeks and for many borrowers, the increase is almost equivalent to a Federal Reserve (Fed) rate hike. The London Interbank Offered Rate (commonly known as Libor) is a commonly used short-term interest rate benchmark. In addition to a measure of interbank lending rates, Libor is used as a reference rate on an estimated $350 trillion of bonds and debt contracts worldwide, including adjustable rate mortgages and floating rate bonds (known as bank loans).

Figure 1 shows that the last significant increase in 3-month U.S. dollar Libor was in late 2015, when the rate jumped by 0.31%, driven by a Federal Reserve (Fed) rate hike. Libor has increased by approximately 0.2% over the past two months; this time without the help of a Fed rate hike, leaving many wondering what is behind the rise. We will examine several potential reasons for the increase, determining which are likely, and which aren’t.

BANK FEARS ARE NOT A DRIVER

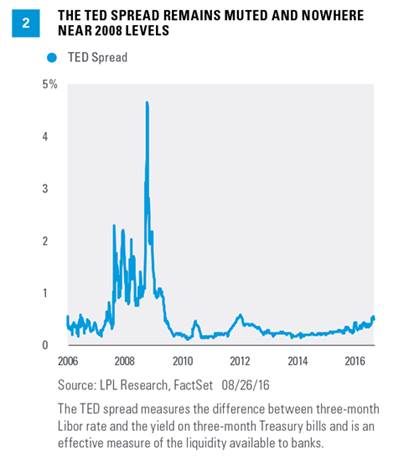

For many, the rise in Libor brings back memories of the 2008 financial crisis, when banks became fearful of lending to one another, leading to an increase in the rates they charged each other for short-term loans. Recent headlines surrounding Brexit, Italian bank fears, and other scary headlines have no doubt amplified concerns that bank weakness may be driving Libor higher. However, a look at the TED spread (3-month Libor minus the 3-month Treasury yield [Figure 2]), a measure of interbank lending fears that gained notoriety during the financial crisis, shows that the recent increase (driven by the rise in Libor) is nowhere near what was experienced in 2008.

Other measures of bank stress, such as credit default swap (CDS) spreads for banks, which reflect the cost of insuring against default, have come down from post-Brexit levels and do not suggest the presence of bank solvency fears. Stronger balance sheets (especially in the U.S.) and supportive policy from global central banks (in Europe and Japan) may also act as a tailwind for banks, potentially reducing the risks of systematic problems like those seen in 2008.

MONEY MARKET REFORM IS A MAJOR DRIVER