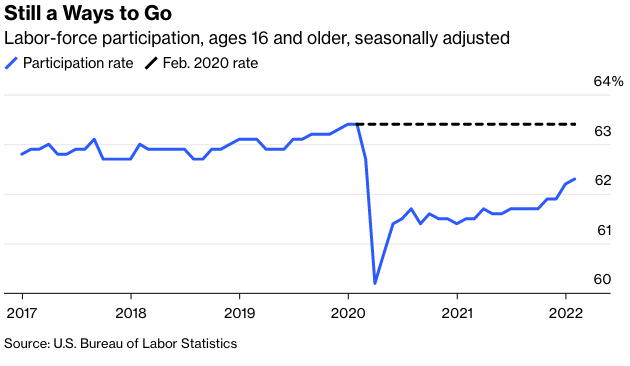

Despite spectacular job growth over the past 22 months, the U.S. labor-force participation rate is still 1.1 percentage points—which amounts to about 1.8 million people—short of where it was on the eve of the pandemic in February 2020.

The labor-force participation rate is the number of Americans 16 and older who either have jobs or are actively looking for them, divided by the population 16 and older. (Uniformed military personnel and those confined in prisons and other institutions are excluded from both sides of the equation.) The fact that participation is still so much lower, even as the unemployment rate moves close to pre-pandemic levels—it was 3.8% in February, versus 3.5% in early 2020—is both an explanation for some of the strange things going on in the labor market these days and a phenomenon that itself calls out for explanation.

Part of what’s going on is just that Americans are getting old, with the eldest members of the giant baby boom cohort turning 76 this year. By the estimate of economists Jason Furman and Wilson Powell III, 0.3 percentage point of the decline in labor force participation since February 2020 can be chalked up to the aging of the population since then.

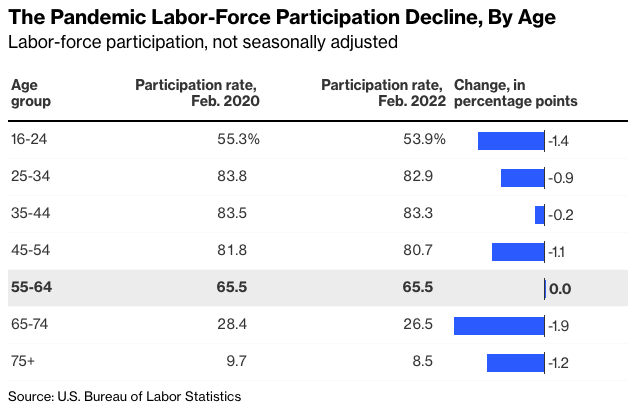

That still leaves a 0.8-percentage-point gap, though, and there are some interesting shifts within age groups that may help explain it. Because the Bureau of Labor Statistics doesn’t adjust all of its age-group numbers for seasonal factors, comparisons that mix months can be misleading, so the February jobs numbers released last week provide a good occasion to look back at what’s changed since just before the pandemic in February 2020.

The general pattern is smaller losses among those in their prime career years and larger ones for those nearer the beginning and the end. The 45-to-54-year-olds are a big exception, and I’ll admit straight away that I don’t know what’s going on there. The group’s labor-force-participation decline has been concentrated among those 45 through 49, has affected men and women similarly and does not seem to be connected to population adjustments that the Bureau of Labor Statistics made in January to incorporate the results of the 2020 U.S. Census (that is, there was no big drop from December to January). Maybe it’s a fluke, maybe it’s not.

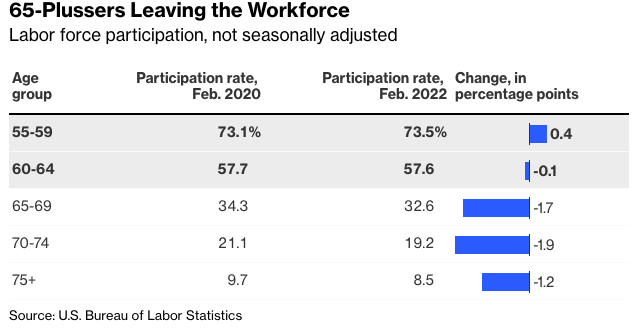

The participation declines among those 65 and older aren’t a fluke, and a lot has been written about them already. A pandemic that was most dangerous for the elderly, coupled with an asset-price boom that was kind to those with retirement savings and home equity, led a lot of Americans 65 and older who were still working to retire.

Some of these people will unretire if the Covid-19 threat continues to recede and the job market continues to boom, but the hit to labor-force participation among those 65 through 74 has been so big that it’s hard to see the gap being closed quickly. Those in their late 50s and early 60s have been the least likely to drop out of the labor force of any age group, so the best hope may simply be to wait until they (or should I say we, since that’s my cohort) move into their late 60s and early 70s.