Wall Street is growing more confident that there won’t be a recession. But one thing that stood out for me from otherwise decent-second quarter earnings is the number of executives claiming their industries are already in recession.

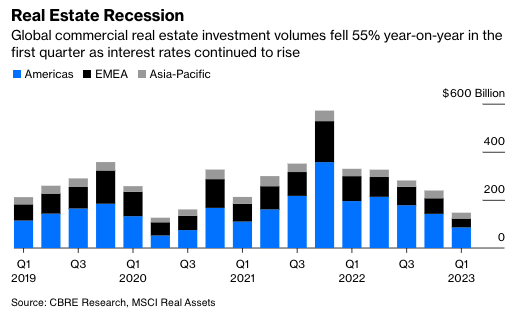

There are sector-specific slumps in manufacturing, chemicals, cardboard boxes, freight, tech/electronics, residential and commercial property, mergers and acquisitions, and advertising. “Maybe the country is not in a recession, but real estate is,” Jordan Kaplan, boss of U.S. property-investment firm Douglas Emmett Inc. said last week. “Our industry has been in recession and still is,” Jonathan Johnson, chief executive officer of online furnishings retailer Overstock.com said. “I don’t know that we’ve ever seen freight demand fall this far, so far and for so long, without an accompanying economic recession,” David Jackson, the boss of Knight-Swift Transportation Holdings Inc. told analysts.

If the list of struggling industries gets any longer, we may still get a full-blown recession—definitions vary but I’m referring to protracted contraction in economic activity across the economy.

For now, though, conditions match the description of a rolling recession, which is when various parts of the economy shrink at different intervals.

Consumers are splashing out on European vacations, Taylor Swift concert tickets and a Barbenheimer double feature, but they’re not buying as many recreational vehicles or home appliances—the reverse of what happened during Covid.

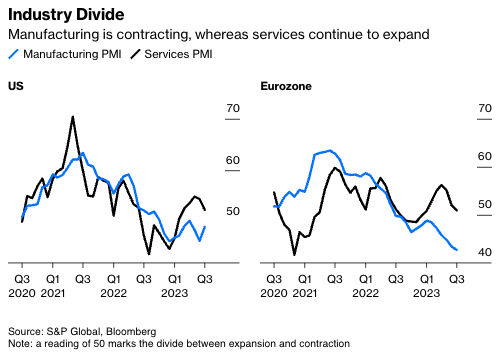

Hence, services economic indices remain fairly upbeat, while similar manufacturing gauges signal distress. Aggregate corporate profits are declining, but they’re still pretty good.

“A series of small, sector specific recessions that roll non-sequentially throughout the economy” could keep the U.S. from experiencing a broad-based downturn, UBS Group AG analysts told clients in June.

Broadly, three types of businesses are currently in a tough spot: durable goods (plus their inputs and transport), sectors sensitive to interest rates, and companies exposed to other companies’ corporate belt tightening.

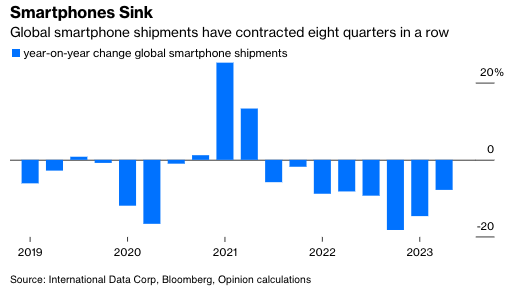

In some cases, conditions are dire. Europe and China are experiencing a “demand disaster,” according to the boss of German specialty chemicals firm Lanxess AG. Meanwhile Carolyn McCall, CEO of U.K. television company ITV Plc, warned about the worst advertising recession “since the global financial crisis.” The electronics industry is going through “the most severe dislocation” in recent history, according to Florida-based supplier Element Solutions Inc. Smartphone shipments have contracted for eight consecutive quarters, a cooling even mighty Apple Inc. hasn’t escaped.

So why isn’t there an official recession (yet)? Firstly, several of these struggling industries are manufacturing-related, and major economies are nowadays weighted much more towards services. One reason the Germany economy is struggling so much is it’s still heavily reliant on making stuff.

Second, hard-hit sectors aren’t uniformly bad. Within depressed manufacturing, there are pockets still going gangbusters: Large listed industrial companies like Caterpillar Inc. are benefiting from a subsidy-driven capex boom; autos and aerospace also remain strong.

In construction, investment in new battery and semiconductor plants is offsetting the housing and office slump. In technology, personal computer sales have sagged even as tech companies gear up for an artificial intelligence arms race. And so on.

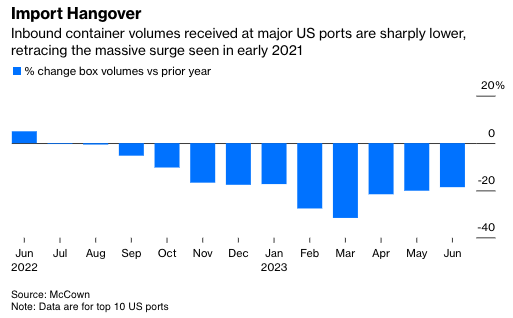

Third, though companies are experiencing large sales volumes declines, much of the shortfall often stems from customer destocking. Due to supply chain upheaval, clients overordered to ensure they received enough and they’re now running down those inventories to preserve cash.

There comes a point when customers run down their stock levels so far they have to buy. German chemicals bellwether BASF SE said inventories had likely reached a trough, which should support a gradual recovery in demand. Analysts say similar about the smartphone market. However, container-shipping giant AP Moller-Maersk A/S warned on Friday that a goods inventory correction that began late last year would persist until at least the end of 2023. So I’d say the jury’s out on those green economic shoots.

Of course, these hard-hit industries don’t operate in insolation—ocean shipping and trucking volumes are shrinking because manufacturers aren’t producing as much. On Sunday, trucking firm Yellow Corp. filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, part of a burgeoning wave of corporate insolvencies.

Similarly, the advertising recession has been exacerbated by tech and telecoms firms reining in their spending. “They're clearly going through something that is more protracted than any of us thought,” the boss of ad agency Interpublic Group of Cos., Philippe Krakowsky, told investors last month.

If too many industries experience a recession at once, a harder economic landing and job losses could follow. I worry most about Europe, where executives warn the continent isn’t competitive due to high energy bills.

Last week, Lanxess announced it may shut as many as two chemical plants in western Germany, with the potential loss of more than 100 jobs, because they are no long economical to run. “Deindustrialization is beginning,” CEO Matthias Zachert warned.

It won’t be the last company to cut its losses here: “People are considering whether it makes sense to produce in Europe,” BASF boss Martin Brudemueller told investors last month, calling the situation an “emergency.”

It’s easy to see how a rolling recession could yet become a plain old recession.

Chris Bryant is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering industrial companies in Europe. Previously, he was a reporter for the Financial Times.

This article was provided by Bloomberg News.