Commodity prices have soared the last two weeks as a result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, drawing novice investors looking to make a quick buck. Many are already getting burned by their lack of knowledge.

Investing in commodities is more complicated than investing in stocks. In commodities, all the action occurs in the futures market because there aren’t any liquid markets for things like spot oil, gas or corn. Then there’s the margin system—to trade commodities futures you must deposit some initial margin into an account and then you are subject to the ongoing vagaries of adhering to margin requirements. But most of the investing public doesn’t want to deal with all that, so they just gravitate to the growing number of exchange-traded funds tracking single commodities or baskets of commodities. Here, too, the risks are different than with an ETF that owns stocks.

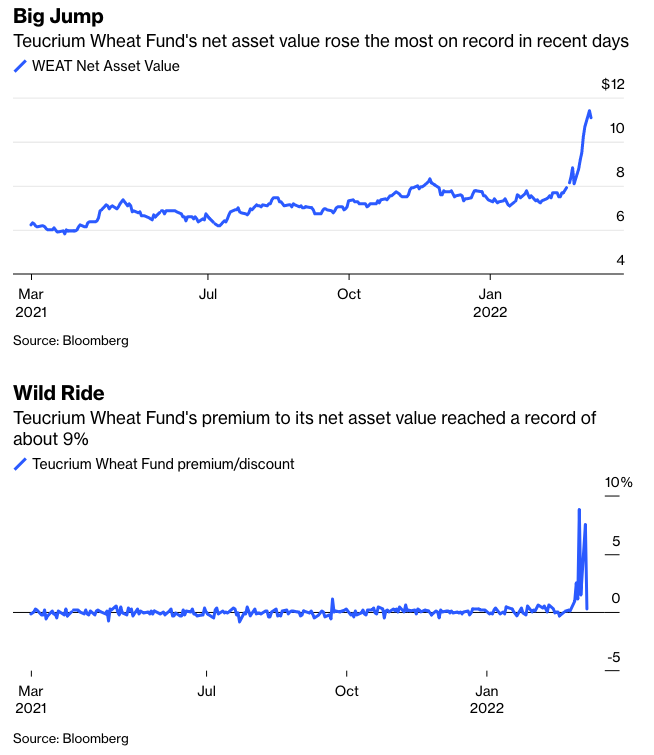

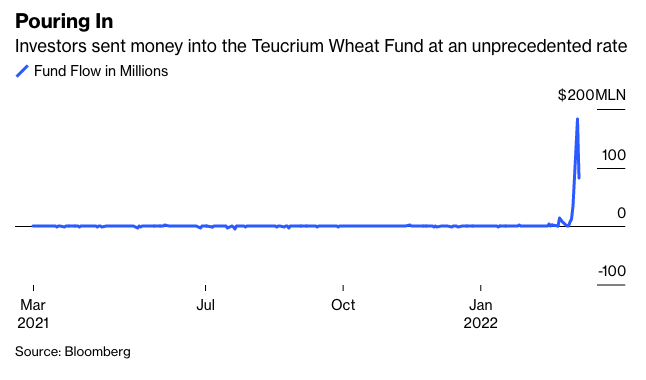

This week we learned that the Teucrium Wheat ETF—ticker WEAT and the only U.S. ETF tracking wheat—was unable to handle the volume of cash that was flowing into the fund from investors looking to profit from a record rally in the price of the grain. WEAT is a special kind of ETF known as a commodity pool, and unlike normal ETFs it needs regulatory approval to create new shares beyond a certain threshold. But so much money flowed in that the threshold was exceeded, creations were suspended and the ETF’s share price diverged from the price of wheat. In other words, the ETF ended up trading at an unusually large 9% premium above the fund’s net asset value. So, anyone who bought the shares significantly overpaid for the underlying assets. (Until this month, the ETF had never lured more than $35 million in a single day. It gathered almost $183 million at the end of last week.)

The United States Oil Fund LP—ticker USO—received a lot of unwanted attention in 2020 when oil prices briefly went negative. USO’s shares didn’t go negative, mostly because it rolled its futures exposure out to longer maturities, but got admonished anyway by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission for not adequately disclosing its actions. Even before that episode, people had complained about USO for years because of the high costs associated with rolling its futures contracts to longer maturities was eating into the returns of the fund. (In raw-material markets, futures are typically pricier at longer maturities to reflect the cost of storage over time as well as future demand expectations—a structure known as contango.)

The problem with all this is that futures investors are perhaps more sophisticated than retail stock investors, and are familiar with all the risks inherent in futures (daily trading limits, roll/carry costs), while equity investors are not. Also, the structure of commodity ETFs is such that they take most of the leverage out of what one might get in the futures markets, with their tiny margin requirements, leaving their shareholders with all of the risks and none of the returns. Plus, many futures markets trade around the clock (wheat trades about 18 hours a day). If you have a position in a commodities ETF and something happens overnight that effects prices, you are stuck until 9:30 a.m. New York time before you can do anything to mitigate your risk.

I’m all in favor of the democratization of markets, and I generally approve of the ETF industry’s attempts to securitize things to make them available to individual investors, but on a long enough timeline, there’s a very good chance than every commodity ETF or ETF based on futures will break. The problem is that these products are really flypaper for idiots, the larpers who fancy themselves the second coming of Paul Tudor Jones, trading macro with the big boys.

But the institutional investors don’t have to deal with any of these problems, because they’re dealing directly with the futures markets. After all these years of securitization, I am starting to wonder if turning food and energy and volatility into products that retail investors can trade is such a good idea. In my experience, retail investors don’t understand the risks. They certainly don’t take the time to read a 90-page prospectus.

One good thing about having someone trade wheat in ETF form as opposed to futures form is that in the world of equities you’re dealing with the Regulation T margin system, and there’s a limited amount of leverage investors can use. It’s harder to lose your money trading a wheat ETF than it is trading futures, where you can be short a market only to have it go limit up a couple days in a row, which just happened to wheat.