When it comes to prime-age workers, two problems need to be addressed: drugs and disability. A 2018 paper published by the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland estimated that 44% of the decrease in labor force participation observed since 2001 could be ascribed to prescription opioids. The share of working-age Americans claiming Social Security Disability Insurance has roughly doubled in the past half-century, from 2.2% in 1977 to 4.3% last year. Local governments have a financial incentive to classify people as disabled because they then become the federal government’s responsibility, even as disability programs provide scant training and work placement to people who are thus classified.

Improving Vocational Training

Some companies are responding to the shortage of job-related skills with innovative solutions. Capital One Financial Corp., in banking IT, and DaVita Inc., in kidney dialysis, are establishing internal boot camps where they pay their employees to learn for a month or so and then quickly move them to a job. Others are reengineering work to reduce the amount of human labor it requires, building up the army of checkout machines that beep at us in shops or the tablets in restaurants that allow us to order without seeing a member of staff. Revature LLC, based in Reston, Virginia, blends training and temporary staffing into an “earn and learn” business: It takes on recent college graduates, trains them in high-demand software skills, and then hires them out, for a consideration, to its corporate clients. Recruits have to work for Revature for two years, by which time they have plenty of experience to put on their resumes.

Still, why not address skills shortages earlier in the educational system so that students come out of school ready to work rather than having to spend four years in college only to find themselves unemployable? Why not reinvent America’s great tradition of providing technical education at school rather than expecting everybody to go to college?

Over recent decades, America’s training system has been sacrificed to the cult of the university. Schools have focused overwhelmingly on getting their students into college while empire-building universities have taken over as much of post-school education as they can, from nursing to journalism training. Professors are selected on the basis of their ability to advance research rather than transmit market-ready skills. This has reduced the number of educational on-ramps into the middle class into just one, marked “college” and with a hefty toll. It has simultaneously created a mismatch between the labor market and the educational system: However well designed to produce recruits to the learned professions, universities are ill-suited to training people in practical skills, particularly in fast-changing ones such as new programming languages.

Germany’s system provides a successful alternative to the U.S.’s college-first model: technical schools that enjoy “parity of esteem” with academic schools, and apprenticeships that give young people a chance to earn a living (and avoid accumulating debt) while at the same time learning a useful trade. Far from ignoring general principles, Germany’s vocational education provides a different way of teaching them, starting with the particular and working to the general — an approach that appeals to many practical-minded young people. And Germany’s system does more to integrate non-academically-inclined young people into the labor market than one that confronts students with a choice between loading themselves down with student debt in return for a degree that might not render them employable, or being treated as a failure because they haven’t been to college.

Can China Surpass The U.S.?

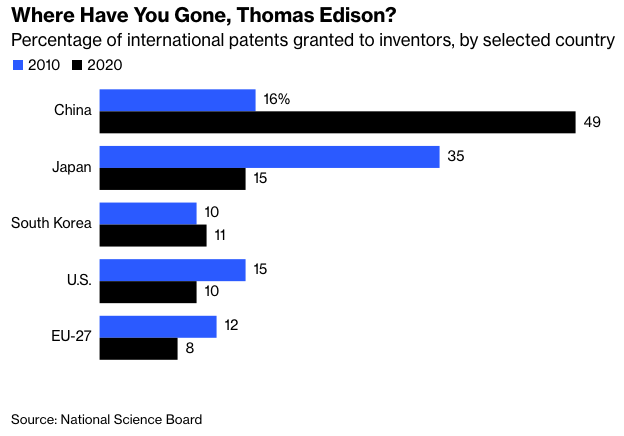

America is also confronting a problem of unprecedented historical scale: a fast-growing rival power forging ahead of it in critical sectors. In each of the foundational technologies of the 21st century—artificial intelligence, semiconductors, 5G wireless, quantum information science, biotechnology and green energy—China is either competitive with the U.S. or outstripping it. The National Science Foundation just confirmed that China has overtaken the U.S. in several key scientific metrics, including the overall number of papers published and patents awarded. China has five times more 5G base stations than the U.S., for example, and produces four times as many electric cars.

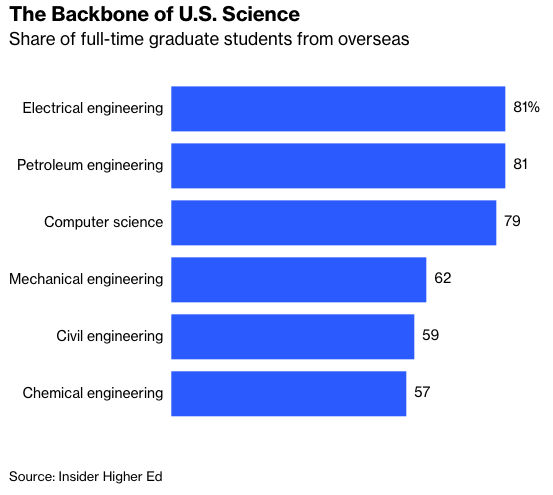

What can be done about this challenge? Graham Allison, of Harvard University, argues that America needs a “million talents” program to match China’s “thousand talents” program. In particular, the U.S. should make it easier for foreign students earning advanced degrees in STEM fields to get a green card.

But it’s not enough. Remaining dependent on foreign sources of talent at a time when other countries are offering better opportunities for their best talent — and as China threatens to turn off its talent spigot — is risky. The sine qua non for reviving America’s economic and technological dynamism is improving its ability to generate more top-class talent internally: first by spotting talent that is currently lying fallow, then by cultivating it more carefully and, it is important to add, more lovingly. That will require reorienting its educational system away from equality of results and toward equality of opportunity.