Like many people my age, I look back fondly on my free-range childhood. Now many of my generation have become neurotic helicopter parents — and their children are paying the price.

Over the last 60 years, in nearly every wealthy country (except France), the amount of time parents spend with their kids has steadily increased. And while parental engagement is better than parental neglect, this hyperattention may be harming children.

A recent paper in the Journal of Pediatrics speculates that the increased anxiety and worsening mental health of children is correlated with more time spent with parents and less in unstructured, non-supervised play. Historically, free play and time away from parents was an important part of childhood: It helped children develop independence, learn to handle conflict and disappointment, and feel a sense of control over their environment.

Now women spend more time with their kids than they did in the 1960s — which is itself extraordinary, because far more women work today. Part of it can be explained by technology; household chores take less time than they used to. People also have more money and fewer children, allowing parents to lavish resources on their kids. And some of it is undoubtedly due to a more cutthroat economy and culture. Parents shuttle their kids to various activities and help them with their homework because they want them to get ahead.

The problem is that overbearing parenting robs children of a sense of well-being and prevents them from developing critical risk-taking skills. Children need to learn that success comes not from playing it safe and doing everything right, but from taking risks and bouncing back from failure.

This will be an important lesson for their future careers. People who take a risk to start a business tend to earn more. Even if they have a boss, people who take risks on the job (within reason) can advance more quickly. There are also gains to be made from moving or just changing jobs. All of this requires comfort with uncertainty and ambiguity. And the benefits are more than just personal: America depends on smart risk-taking to fuel economic growth.

Yulia Chentsova Dutton, a cultural psychologist at Georgetown, has found that a child’s “age of release” — that is, the age at which they are first allowed to go places alone or unsupervised — has an impact on their ability and willingness to take risks later in life. She estimates that this age has increased by 6 or 7 years over the last few decades in the US, to between 12 and 14 years old. She once asked her students how old they were before they were allowed to play alone, she tells me — and they laughed and said by the time they were allowed to be alone, they were too old to play.

Each new class, she says, seems more anxious and less able to assess and take risks. More and more students are afraid to take public transportation, and some are reluctant even to leave campus. When she asks them to recall a hard or scary experience, they will mention things that would not have qualified a few decades ago, such as being approached on the street by a stranger.

There are some advantages to parents spending more time with children. Partly as a result, childhood has never been safer. And it’s important to point out that spending more time with the kids is not an option in many single-parent households, which tend to be lower-income. Still, when it comes to parents spending time with their kids, America may be past the point of diminishing returns.

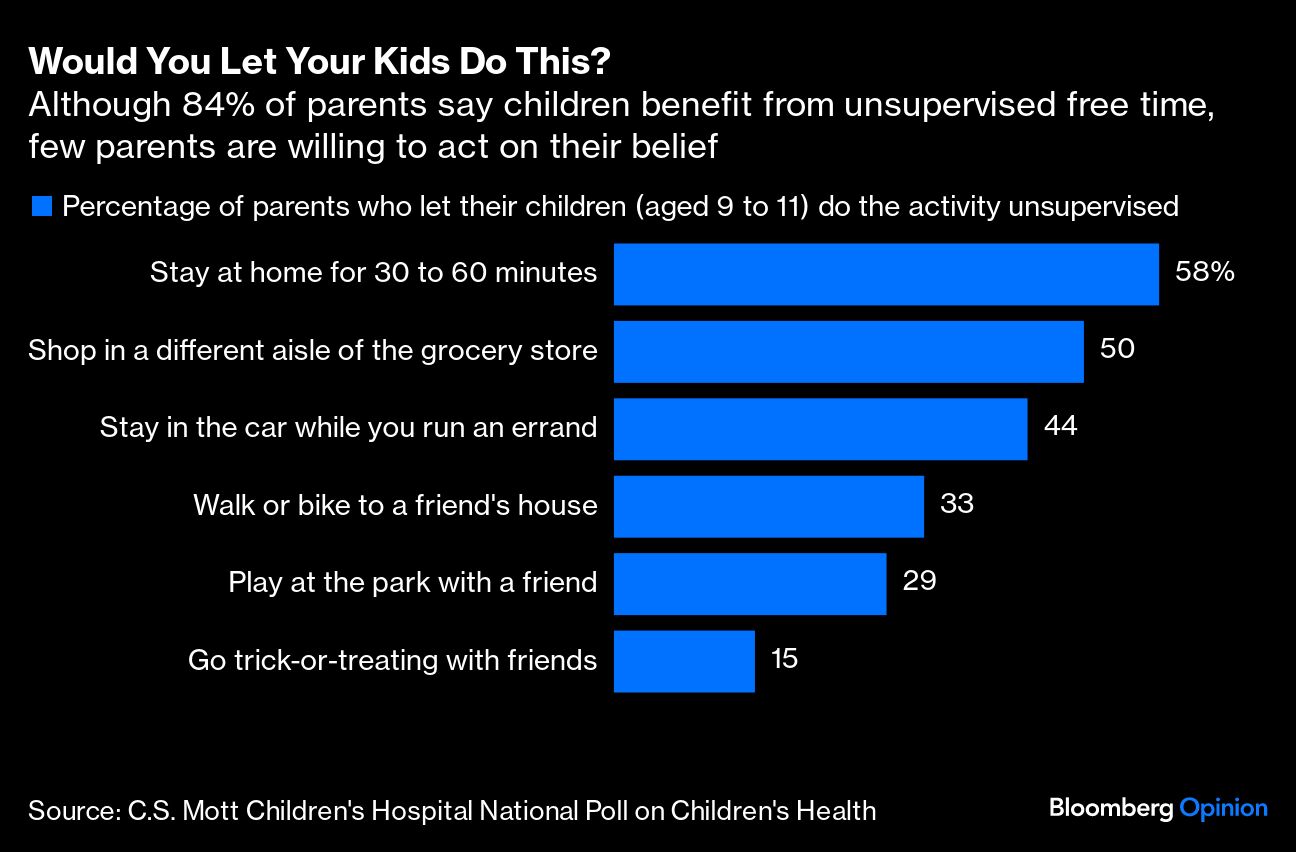

Would You Let Your Kids Do This? | Although 84% of parents say children benefit from unsupervised free time, few parents are willing to act on their belief

Reversing this trend is hard. In a recent poll, 84% of parents say their 9- to 11-year-old would benefit from doing more things on their own — but they find it hard to grant much independence. Only 33% of those same parents would let their child walk or bike to a friend’s house alone, while just 50% would let them get an item in the grocery store while the parent is in another aisle. And, perhaps most sadly, only 15% would let their children trick-or-treat with other kids and no parents.

There is a great deal of social pressure for parents to be highly involved in their children’s lives, and a great deal of shame if they are seen as neglecting their children. And in an arms race of enrichment, who wants to risk leaving their kids behind? This has it backwards: The best way for any parent to make sure their children aren’t left behind is to teach them how to manage the risks they will need to take to get ahead.

Allison Schrager is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering economics. A senior fellow at the Manhattan Institute, she is author of “An Economist Walks Into a Brothel: And Other Unexpected Places to Understand Risk.”