One part of the problem has been a too-high U.S. dollar, which has contributed to chronic trade deficits. Indeed, since 1980, the U.S. has had an average trade deficit of 2.6% of GDP and has failed to run a trade surplus in even one year. If we are buying substantially more of everyone else’s stuff than they are buying of ours, we are, right away, liable to see insufficient demand for the goods and services we produce.

However, a second major cause has been rising income inequality. According to data compiled by Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, from 1951 to 1981, the share of income received by the top 10% of households was remarkably steady, averaging about 34% of the total. (See “Income Inequality in the United States, 1913-1998”, by Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez, Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(1), 2003, with data updated to 2018 on the website of Emmanuel Saez.) However, since then it has soared, exceeding 50% for the first time in at least a century in both 2017 and 2018.

The reason this is such a potent macro-economic issue is that better-off households tend to spend much less of their income on goods and services. Indeed, in 2019, according to the Consumer Expenditure Survey, the richest 10% of households spent just 64% of their after-tax income and saved the rest. The other 90% of households, on average, spent 99% of their income, many of them, of course, borrowing to finance spending. The steady growth in the income share of the richest households has contributed, simultaneously, to strong and rising demand for financial assets and lackluster demand for goods and services.

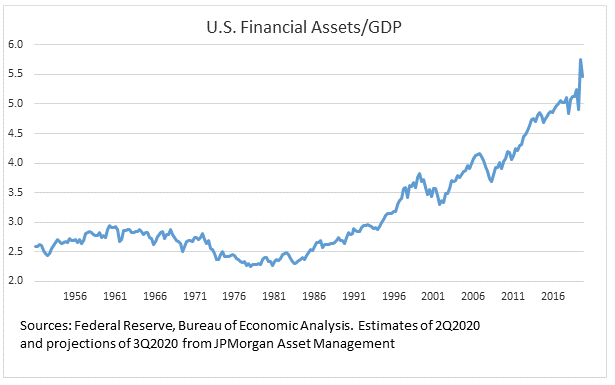

As an important aside, this can also, of course, partly explain some of the surges in asset prices in recent decades, which have occasionally ended in tears, as in the case of the tech bubble that ended in 2000 or the housing bubble that ended in 2007. Nor has this trend come to an end. Indeed, since the mid-1980s, the growth in asset prices has very consistently outpaced the growth in consumer prices. Consequently, the ratio of the value of U.S. financial assets to U.S. GDP has risen from an average of 2.6 times between 1951 and 1985 to roughly 5.5 times today.

The Lack Of Aggregate Demand: The Right Remedies

Over the years, the Federal Reserve has tried to remedy this lack of demand for goods and services by running a persistently easy monetary policy. However, as we have often argued in the past, cutting interest rates from very low levels is, at best, ineffective and, at worst, counterproductive, if you are trying to boost aggregate demand. While such rate cuts can make investment spending look more profitable, they also undermine confidence and reduce consumer interest income in a way that hurts consumer spending and thus negates their effects.

A more effective solution would start with a coordinated approach between the Federal Reserve and the Federal Government to lower the U.S. dollar exchange rate to levels consistent with trade balance. A second part of a solution would be to encourage more balanced spending across U.S. households. One way this could be achieved would be by raising taxes on the rich to fund lower taxes for poorer or middle income households as well as adopting a higher minimum wage and a stronger social safety net so people did not feel so obligated to save for old age or a potential health problem. Importantly, all of this could be achieved without flooding the economy with liquidity or running massive federal deficits. However, it would require tough political choices.

The MMT Solution

The allure of Modern Monetary Theory is that it seems to imply that these choices don’t, in fact, have to be made.

MMT starts with a logical truism, namely that a sovereign government, in control of a sovereign central bank, can never be forced to default on its own currency debt. This being the case, in an economy where there is a lack of aggregate demand, a government can just ramp up government spending or cut taxes to remedy the situation. As the deficit rises, the central bank can buy more of the government debt to prevent any increase in long-term interest rates. MMT argues that there isn’t any problem with this until inflation appears. If inflation does crop up, the government can just raise taxes to quell demand.

Provided it has a light touch on both the gas and the brake, the economy can emerge from recessions faster and hover at close to full employment for longer. Indeed, just to make sure that full employment is sustained, the advocates of MMT also suggest that part of this deficit spending could be devoted to providing a job guarantee for everyone that wanted to work, with the government hiring those the private sector won’t.