The yield on 10-year Treasuries went above 5% last week for the first time since July 2007, when the first Transformers movie was topping the box office and the Dow Jones Industrial Average surpassed 14,000 for the first time in history.

Higher long-term rates are pushing many investors from stocks into bonds. The effect of interest rates on stock returns is complex, and a lot of ink is spilled arguing whether the 5% level for 10-year Treasury yields is a signal to dump stocks or pile into them. Let’s ignore the theoretical arguments and just look at the data.

Chart 1 goes back to the Nixon Shock of 1971 (prior to that, in the gold standard days, the economics of interest rates were different). You can see here that if you buy the S&P 500 when the 10-year Treasury yield is below 4% or above 8%, you have almost always been rewarded in the past with between an 8% and a 16% annualized real (that is, adjusted for inflation) return over the subsequent ten years. Buying when the 10-year Treasury yield is around 5% has historically been the least attractive time.

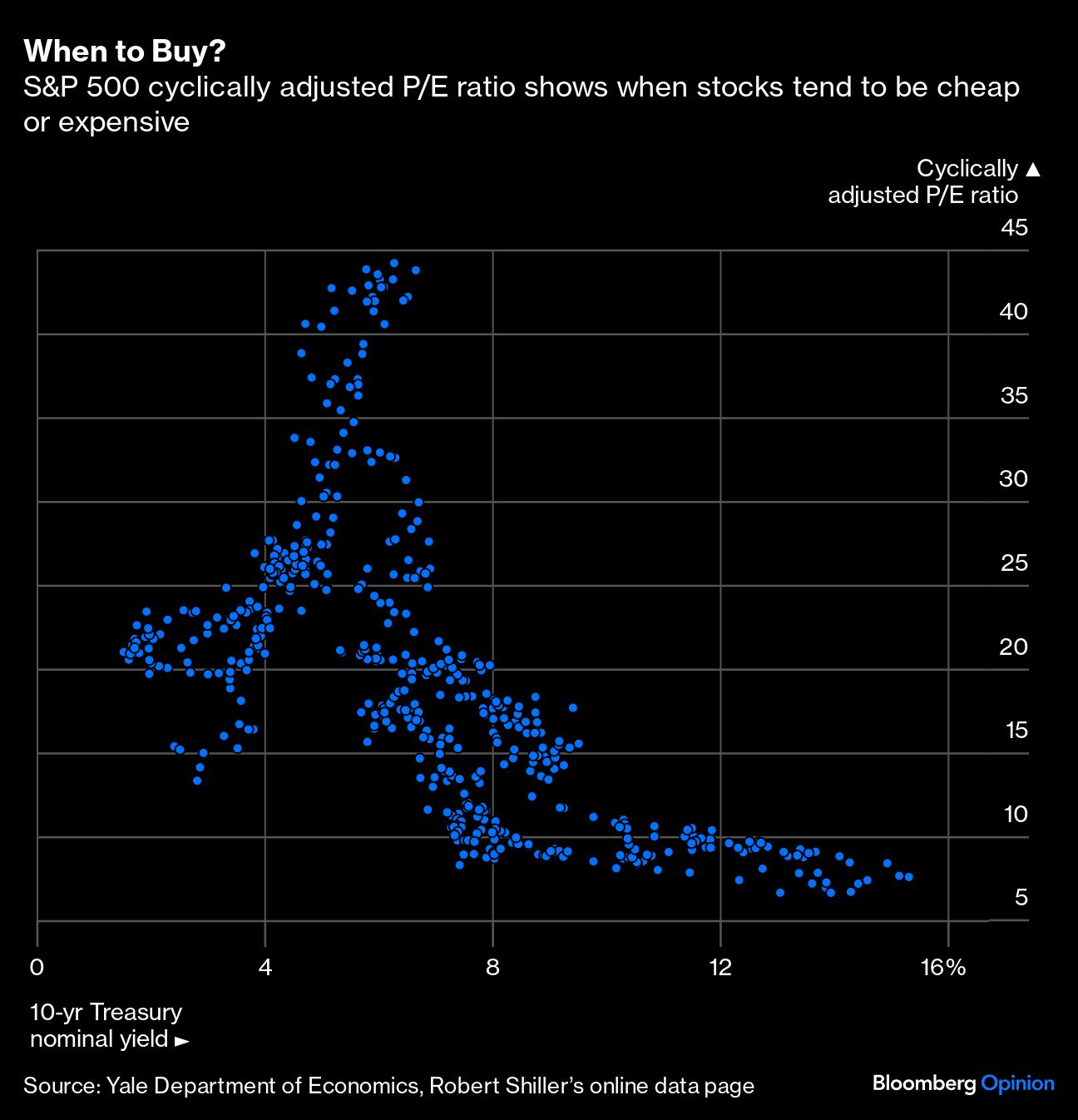

Chart 2 sheds light on the reason for the pattern. It shows the S&P 500 cyclically adjusted price earnings ratio, which signals expensive stocks when the reading is high and cheap stocks when it is low.

If you ignore the chart between 4% and 7% Treasury rates, you see CAPEs generally decline with rising long-term interest rates. This makes sense economically. High long-term interest rates either mean high inflation or investors demanding high real returns. The former is bad for stocks because inflation is bad for the economy, and causes the Federal Reserve to raise short-term interest rates, which is bad for equities. The latter is bad for stock prices because investors demanding higher real returns makes the expected future cash flows of stocks less valuable. Moreover chart 1 validates these CAPEs in the sense that S&P 500 investors seem to do roughly as well buying when 10-year Treasury yields are low or high.

But when 10-year Treasury yields are in the middle — 4% to 7% or 8% — it’s bubble time. CAPEs soar, investors overpay for stocks, and 10-year annualized real S&P 500 returns are often low or negative. The CAPE is currently about 29, right around where you would expect when 10-year Treasury yields are 5%.

Looking at historical data, buying stocks when the 10-year Treasury yield is 5% and CAPE is 29 is not a terrible idea — you’ve made money after inflation over the next ten years more than you’ve lost, and you can hope for annualized real returns of up to 6%, which is very good. But looking at the range of historical outcomes, including annualized real returns of negative 6%, it’s tempting to just grab the 5% guaranteed by dumping stocks and loading up on long-term bonds.

Unfortunately, the 5% 10-year Treasury yield is a nominal return, not a real return. The Treasury is only offering about 2.43% on 10-year inflation-protected bonds, which pay the inflation rate plus 2.43%, so are real yields.

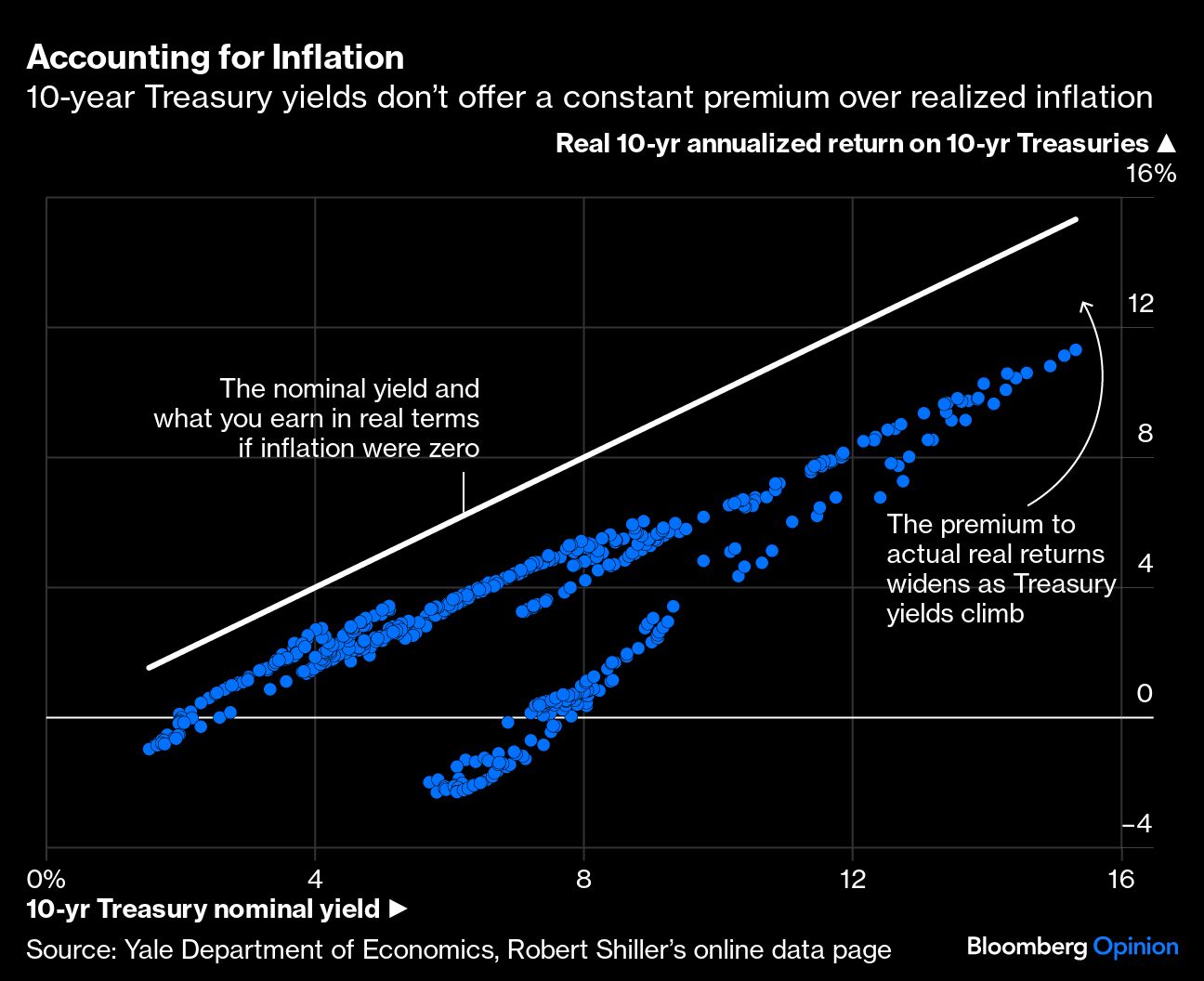

What if you’re willing to take the inflation risk? Chart 3 shows real annualized returns on 10-year Treasuries or what you earn after stripping out inflation.

There is a crude efficient markets argument that the expected real yield on 10-year Treasuries should be the same for all nominal yields at the time of purchase — in other words, the 10-year Treasury yield should represent a constant premium above the expected inflation rate. But you can see that’s not true. When the nominal yield is low, the actual real return is consistently about 2% below it — or average inflation over the next ten years is about 2%. When the nominal yield is high, the actual real return is usually about 4% below it. So when 10-year Treasuries offer higher yields you have historically gotten higher inflation, but have still retained a higher after-inflation return.

But you also notice that once nominal yields get to the high 5%s, there is a risk that inflation will be about 8% instead of the usual 2.5% or so in that range. The unexpected inflation risk declines as 10-year Treasury rates increase, both because it goes down in absolute terms, and because you have a higher notional yield to offset it.

Looking at history, a 5% 10-year Treasury yield is below the level at which long-term investors have lost due to unexpected inflation shocks. If you trust that, 10-year Treasuries seem to offer about the same expected 10-year annualized real returns as 10-year government securities indexed to inflation or TIPS. If not, if you think there’s a significant probability of a large inflation shock, TIPS would seem to be both safer and offer a higher expected return. If you stick with fixed coupon securities you can find high-quality corporate bonds that offer 1 percentage point to 1.5 percentage points premia over Treasury yields. If you prefer prepayment risk to credit risk, you can get similar premia buying mortgage securities backed by the full faith and credit of the US government.

If you trust history, long-term, good-quality corporate bonds or mortgage securities seem to offer high probabilities of delivering about the best 10-year annualized real returns you can expect from the S&P 500 given the current level of Treasury yields and the cyclically adjusted price earnings ratio. Stocks have a lot more downside risk. Unfortunately, as always, past experience is no guarantee of future returns.

Aaron Brown is a former head of financial market research at AQR Capital Management. He is also an active crypto investor, and has venture capital investments and advisory ties with crypto firms.