Certificates of deposit are one of the oldest, safest bank products around, but investing in shorter-term CDs right now just isn’t worth it. Yet people are still flocking to them.

Data from the Federal Reserve shows that savers have been putting a lot more money into “small-denomination time deposits,” or CDs with balances of less than $100,000. As of the end of last year, those deposits totaled $357 billion—more than four times the amount a year earlier.

On some level, the enthusiasm is understandable. CD yields have been on a tear (relatively speaking) since last year, and some online banks, such as Capital One, Synchrony and Goldman Sachs’ Marcus, are dangling offers of more than 4% for one-year CDs.

But savers who can afford to park their cash for up to a year would be better off just buying Treasury bills outright. Even money market funds, which are paying pretty generous yields, can’t compete with most T-bills right now, especially after accounting for fees.

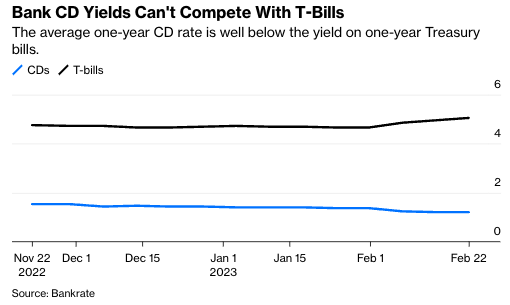

Across the board, the rates for T-bills are higher than those for CDs of comparable maturities. Despite a handful of outliers, the current average rate for a one-year CD is a paltry 1.44%, according to Bankrate, vs. 5% for a one-year T-bill. Big banks are still flush with deposits, so don’t feel the need to turbocharge their CD rates.

T-bills have ticked up even higher over the last couple of weeks because they move more in lockstep with the Federal Reserve’s actions (or anticipated actions) than CDs do. It’s hard to predict of course, but T-bill payouts are likely to stay high with recent strong economic data showing the Fed still has some work to do hiking interest rates to cool the economy.

Even the leading CD offers from online banks can’t compete with T-bills. Take Marcus—you’ll get 3.9% for a six-month CD, 4.5% for a one-year CD and 4.35% for a two-year CD. That sounds pretty good, until you realize that a six-month T-bill will pay you 5.1%, a one-year is at 5% and a two-year Treasury note is 4.8%.

If you’re in a high-tax state, a CD looks even worse if it's in a taxable account. The interest earned from Treasuries is exempt from state and local income taxes; the same can’t be said for CDs.

CDs also carry penalties if you need your money sooner. It varies, but some banks may charge three months’ interest if you withdraw a one-year CD early. For longer-term CDs, you could be hit with six months of interest. With Treasuries, there’s no penalty if you want to cash out before the term is up—you’ll just have to find a buyer on the secondary market and be subject to whatever the prevailing price is when you want to sell. (Money market funds might work better for savers who want to preserve the option to access their cash more easily.)

Some may argue that a CD comes with FDIC insurance (at least through losses of up to $250,000). But a T-bill is backed by the U.S. government and has a $10 million cap.

Sure, there may be concerns about the debt ceiling, but it seems pretty extreme to think there would actually be an intentional default by the U.S. government for the first time in modern history. If the unthinkable happens, it’s likely to damage the economy but not leave bond holders empty-handed; if a 2011 contingency plan is any guide, Treasury would have to keep paying those debts.

You might be able to find an exceptional CD, of course. Ken Tumin, founder of DepositAccounts.com, pointed out a deal worth flagging for CD diehards: Navy Federal Credit Union is paying 5% for a 15-month CD, with the option to add deposits up to $250,000 once the CD is open. That way, you could open a CD with, say, the $50 minimum, and if T-bill rates come down unexpectedly, you would still be able to get a 5% rate on any additional money you put in there.

And some five-year CDs do offer better payouts than five-year Treasury notes. If you believe interest rates will be headed down, locking in that higher rate now might be warranted.

But most short-term CDs are pretty pointless. So why do people keep buying them?

Perhaps one reason is that opening an account on Treasurydirect.gov seems like a pain. But to take advantage of the best CD offers, most people would probably have to open a new online bank account anyway. And investors can always buy T-bills through their brokerage accounts.

Or maybe it’s that psychological hurdle of T-bills not feeling as “safe” as a CD that’s in the bank. Higher payouts do often come with increased risk, but this is one time where that’s just not the case.

Savers, please. Forget short-term CDs. They’re just as outdated as the compact disc.

Alexis Leondis is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering personal finance. Previously, she oversaw tax coverage for Bloomberg News.