China imported close to 1.2 billion tons of iron ore in 2023, up 7% year over year, driven by demand for steel in machinery and shipbuilding.

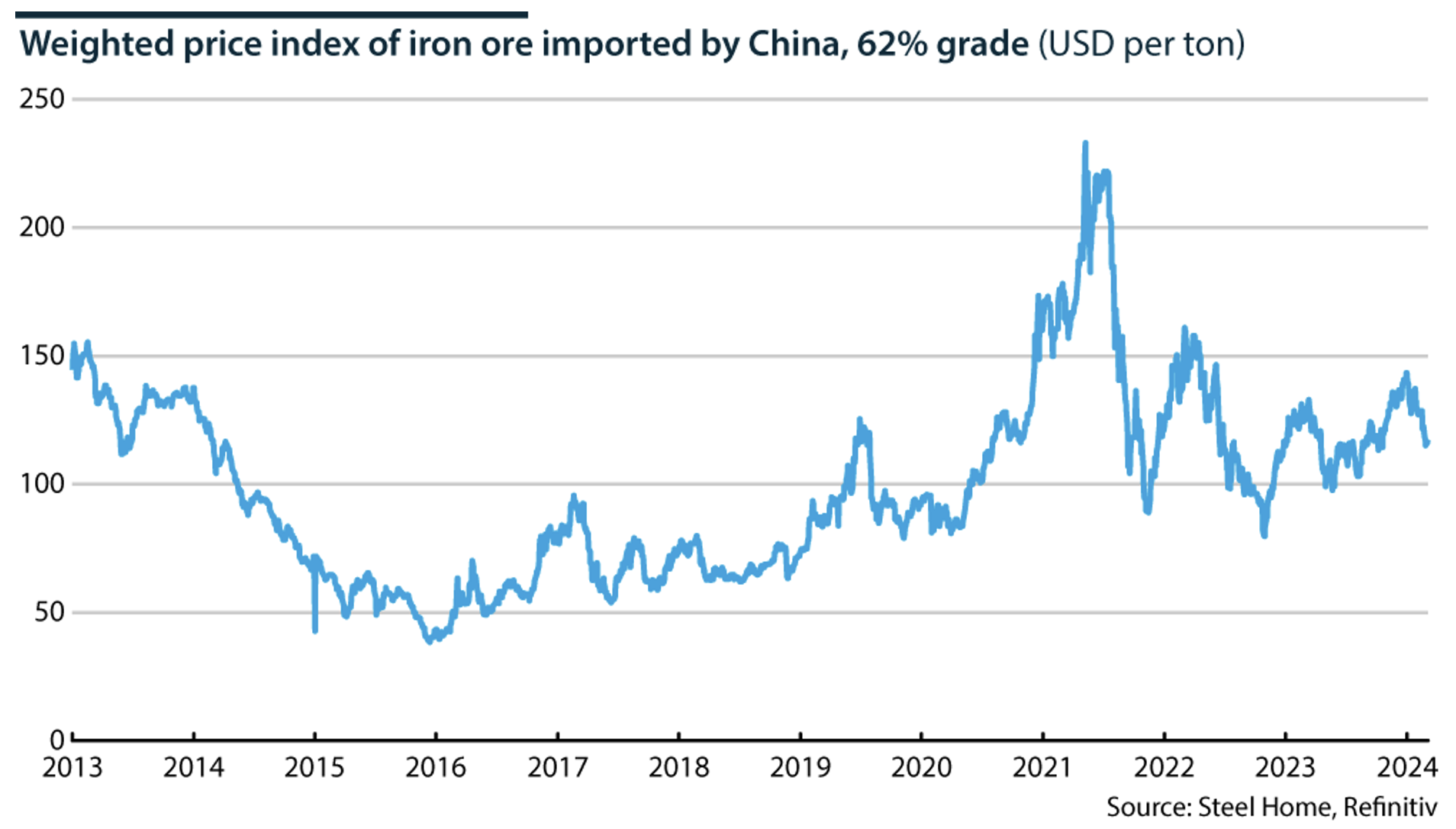

Iron ore prices tend to be seasonal, with the second and fourth quarters outperforming the first and third. However, in spring 2023, when Chinese mills lowered prices of construction-related steel, iron ore futures in Singapore fell for several days.

Nevertheless, demand for iron ore has remained robust due to brisk growth in flat steel production. There has been little sign of stockpiling, with the ratio of monthly imports to port inventory remaining low.

Crackdown On ‘Speculators'

Iron ore prices gained more than 60% between late 2022 and the end of 2023. This is a fraction of the increase in the first year of the pandemic when panic stocking and supply disruptions tripled prices to USD215 per ton.

However, China's economy—particularly domestic construction—is much weaker than three years ago.

Last year, steelmakers increased prices of long products such as rebar to offset margin pressures from the iron ore rally. This annoyed Beijing's policymakers, who are looking for ways to stimulate the property sector while capping steel costs.

Prices stalled after China's National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) vowed to curb "unreasonable" price gains. The government pledged to continue strengthening the exploration of domestic resources and to boost steel recycling.

The NDRC is increasing its supervision of iron ore spot and futures prices and promises to crack down on illegal activities, including disseminating information on price increases, metal hoarding, and activities aimed at inflating prices.

Pricing

Since the Brumadinho tailings dam collapse in Brazil five years ago, the iron ore price has found support at USD80-90 per ton. However, prices tend to overshoot occasionally.

Beijing launched the China Minerals Resources Group (CMRG) in 2022 to strengthen its price control capacity. Twenty-five steel mills have joined this consortium, which covers around 60% of China's annual iron ore demand (approximately 660 million tons per year).

Iron ore prices were set by negotiations between Australian producers and Japanese customers for many years until China became the major importer. Since 2011, spot prices have largely prevailed.

The Chinese government is now trying to increase its control to reduce price volatility.

CMRG is expected to lead the annual contract negotiations. However, the unclear application of pricing discounts and the group's inability to agree on the most applicable price index for negotiations hamper the oligopsonic project.

Production Costs

Some 95% of listed iron ore producers report cash costs of around USD80-100 per ton, around 50% higher than three years ago. Indian iron ore fine producers need at least USD100 per ton to remain in business, while Chinese domestic iron ore producers not integrated with steel plants require prices of USD90-100 per ton.

The cost increases have been remarkably uniform despite the variety of mining operations and their differential exposure to input costs such as energy, freight, grade and pellet premia, penalties for deleterious materials, maintenance and currency volatility.

The reasons for this are not well understood. One factor is that iron ore supply from countries other than Australia or Brazil—by far the largest two producers, with 2022 exports of 884 million tons and 344 million tons, respectively—has been very price elastic since the market moved to spot-based pricing in 2011.

China's Autarky Drive

The Chinese government is pushing for more supply to be sourced domestically or from overseas operations controlled by Chinese entities. Domestically, the government targets production of 370 million tons per year, compared to 2023 supply of 260 million tons annually. This is too ambitious as it would imply production from deposits characterized by very low grades.

Beijing has been considering reducing production taxes, which are CNY50-150 (USD7-21) per ton, to incentivize domestic mining. Given their reliance on this revenue, local governments are likely to oppose such measures.

Beijing is also encouraging scrap recyclers to bring new supply online, but the promise of a "tidal wave" of recycled steel remains elusive.

Simandou

Guinea's 60 million ton per year Simandou iron ore project is the most critical element of China's strategy to liberate its iron ore demand from Western—and particularly Australian—supply. The mine is expected to begin production in 2026, reach full output after 30 months, and then operate for 26 years.

London-headquartered Rio Tinto holds a 53% interest in the Simfer consortium, with China's Chalco Iron Ore Holdings holding the remaining 47%. Rio Tinto describes the project as "the world's largest untapped high-grade iron ore deposit and largest greenfield integrated mine and infrastructure investment in Africa."

Simandou has a proven ore reserve of 273 million tons, with a high average grade of 66.4% iron and low levels of impurities.

The capital cost of the mine and associated infrastructure, including the construction of 343 miles of railway and a port, is USD11.6bn.

Construction progresses slowly as the parties negotiate budget terms and the precise schedule with the Guinean government. Rail capacity remains the main bottleneck, and the project timelines will likely have to be extended.