The rapid spread of the omicron variant has sent office workers back to their kitchen tables and put the business travel recovery on pause. But the longer-term outlook is actually looking brighter these days.

First, it’s important to note that despite the doomsday predictions early in the pandemic, business travel isn’t dead so much as hobbled. Before the omicron variant sent demand plummeting, domestic corporate volumes in early December were about 40% below 2019 levels, United Airlines Holdings Inc. said this week when it reported fourth-quarter earnings. That’s a meaningful recovery; on the same measure, corporate travel was 90% below pre-pandemic levels in the early part of the second quarter and down 60% as of June. United expects the rehabilitation trend to get back on track by the end of February as the surge in cases ebbs and more companies start to treat Covid-19 as endemic. But there’s clearly still a ways to go.

One interesting divide that has emerged is that smaller businesses have proved much more willing than larger corporations to put workers back on planes. At American Airlines Group Inc., travel demand in the fourth quarter from small and medium-sized businesses returned to 80% of its pre-pandemic level, compared with only 40% for large companies. A Jefferies Financial Group Inc. survey of U.S. adults who took business trips in 2019 found that those who worked at companies with fewer than 1,000 employees were much more likely to predict a return to pre-Covid patterns in the near term. About 80% of that group on average expected to be traveling as much for business as they were before the pandemic by the end of 2022, compared with just 55% of workers at bigger enterprises. Among the 9% of previous business travelers who said corporate trips would never return to a 2019 pace, two-thirds work at companies with more than 1,000 employees, the Jefferies data show. The results of the survey were published in January.

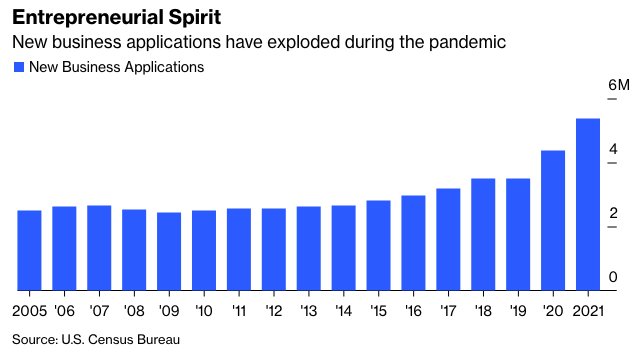

This makes sense in the short term: Corporate giants with storied reputations and long-standing customer relationships are less likely to lose out on opportunities by keeping workers at home a little longer. The gears of change grind slowly at bigger companies, particularly in the face of a constantly evolving virus. Upstarts don’t have the same luxuries—and there are many more of them these days. Entrepreneurs filed a record 5.4 million new business applications last year, almost double the annual average between 2005 and 2019, according to data from the U.S. Census Bureau. This creates new opportunities for the airlines. Corporate giants typically negotiate deals for preferred rates in exchange for their premium business, but most carriers haven’t targeted small and medium-sized entities in the same way. That means the cost of sales for this category is much lower and more akin to that of leisure passengers, even though small businesses tend to mimic their larger peers in their tendency to buy higher-priced last-minute tickets, Vasu Raja, American Airlines’ chief revenue officer, said on a call this week to discuss earnings.

But a world in which smaller entities send workers out on the road to chase new opportunities and collaborate with colleagues while larger ones are content with Zoom calls in perpetuity feels weird and highly unlikely. At Siemens AG, some internal meetings can be done virtually and certain equipment can be maintained just as effectively by remote systems. But it’s “one of those companies” that relies on aviation to move products around the world and get people to where they need to be, Barbara Humpton, president and chief executive officer of the industrial giant’s U.S. operations, said in an interview.

One argument against a full-scale revival of corporate travel has been that large public companies are under increasing pressure to reduce their carbon footprint, and curbing flights is one of the easiest ways to accomplish that. But sustainable aviation fuel(SAF) has the potential to change that calculus, particularly over the longer periods that many companies have given themselves to reach carbon neutrality. SAF—which is derived from cooking oils, waste and other byproducts—can reduce life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions by as much as 80%, depending on the type of feedstock and how it’s produced. There’s currently only enough production to cover a fraction of global needs, and the little SAF that is available costs significantly more than kerosene. Airlines are eager to change that. In November, British Airways flew an Airbus SE jet from London to New York City on 35% SAF. In December, United flew a Boeing Co. 737 Max jet from Chicago to Washington using 100% SAF in one engine. The latter flight was meant to demonstrate that existing aircraft infrastructure can support higher levels of SAF use than the current 50% blend with traditional fuels allowed by regulators and to increase pressure on governments to subsidize expanded production.

The International Air Transport Association estimates widespread adoption of SAF could help the global aviation industry get 65% of the way toward its goal of net-zero emissions by 2050. Whether SAF availability improves enough to actually allow widespread adoption remains to be seen. But corporate travel customers are already benefiting from airlines’ efforts. Siemens is part of United’s Eco-Skies Alliance, which allows companies to contribute to the purchase of SAF for the carrier’s network. This investment has addressed 17% of Siemens’s typical annual environmental footprint from business travel on United flights and reduced its carbon emissions by 2,400 metric tons, Humpton said. Siemens plans to make similar SAF investments with other frequently traveled airlines.

It makes sense that ticket prices would be higher for SAF-powered flights because a trip that relies on kerosene carries an additional carbon cost, Humpton said. Without the benefits of the greener alternative fuel, companies striving for carbon neutrality would need to invest in offsets or otherwise make up the emissions impact. Siemens aims to be carbon neutral in its own operations by 2030 and to establish an emissions-free supply chain by 2050.

For months, airline CEOs have been telling anyone who would listen that the work-from-home lifestyle could actually open up new business travel opportunities, but there wasn’t much concrete evidence to support that theory—until recently. Earlier this month, Yahoo Japan told its 8,000 employees that they could work anywhere in the country and that the company would pay for them to commute by plane to offices when required. The company, a unit of SoftBank Group Corp.’s Z Holdings Corp., set a commuting budget of 150,000 yen ($1,300) a month for each worker. This may be the start of a larger trend: The Jefferies survey found that more than a third of employees who now had more flexibility to work from home had moved their primary residence as a result. Within that group, 75% said they expected to fly to an office on occasion. This “creates a new type of corporate travel that largely doesn't seem to have been factored into estimates of a recovery,” Jefferies analysts led by Sheila Kahyaoglu wrote in the January report.

Will business travel come all the way back? No one truly knows. But as the world tries to edge back to some semblance of normalcy, there are a lot of reasons to think that the future will include a healthy amount of travel for corporations big and small. Southwest Airlines Co., JetBlue Airways Corp. and Alaska Air Group Inc. round out the main airline earnings next week.