Amazon recently announced that they are combing through the list of things they warehouse and sell to determine which items “can’t realize a profit” (C.R.a.P.). We found it very interesting how they are determining which items to pare from their website list. Simultaneously, the U.S. stock market became an investment market in the last four months of 2018 where you “can’t invest at a profit” (C.I.a.P.). Since late summer all the major indexes have plummeted. Is C.I.a.P. related to C.R.a.P. and can understanding the connection help us prosper going forward?

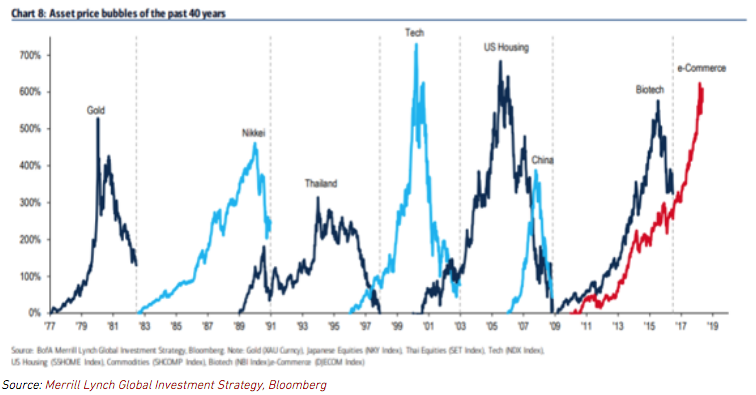

First, the FAANG-trade mania of the last five years was led by Amazon and Netflix. (FAANG stocks include Facebook [FB], Apple [AAPL], Amazon [AMZN], Netflix [NFLX] and Google parent Alphabet [GOOGL].) At its heart, the mania is about e-commerce and massive revenue growth. Public companies were allowed years of unprofitable growth as they sold “C.R.a.P.” to adoring consumers who could sense what a ridiculous bargain free shipping was, or how inexpensive unlimited entertainment was on their relative’s Netflix account. See the chart of maniacal markets since 1977 below:

This e-commerce bubble ranks right up with the worst ones. Since the FAANG stocks (and tech-related companies) reached 30 percent of the S&P 500 Index in August 2018 and started a fight over trillion-dollar market-cap supremacy, it doomed the index to perform poorly when the glam tech stocks got hit harder than the broader stock market in this decline.

Second, how Amazon determines C.R.a.P. is different than how we determine it or how the anti-trust division of the United States may determine it. We believe that most things sold from Amazon’s own inventory lose money when delivery is included. They do it to make their “Prime” membership attractive and to shovel a significant part of that revenue to their technology company, Amazon Web Services (AWS). As we parse their income statements, there is no way to really see if they can make money retailing items because Federal Express and UPS tell us it costs $5 to deliver the packages.

If you deliver 200 packages a year at $5 each, you burn up $1,000 on a $119 Prime membership. We don’t suggest you go on Shark Tank as a contestant with a business model designed to charge $119 for $1,000 of services. Mark Cuban and Kevin O’Leary might ridicule you unmercifully. The only profitable part of Amazon is the membership revenue and the AWS profit.

It makes sense to undercut your competition with free delivery if you can make 36 percent on the revenues you send to your wholly owned subsidiary. No other e-commerce entity has that luxury, hence the interest of the anti-trust lawyers. We believe the U.S. stock market has woken up to the nightmare it created, over-capitalizing revenue-growth stories for years, concentrating success into a small number of people in our democratic capitalist society, and allowing unfair internet-based competition to turn into a bubble.

The market is beginning to understand. The average ticket size of orders on Prime at Whole Foods are lower than a year ago. The revenue grab in groceries is more and more looking like a C.R.a.P. idea right from the beginning. Kroger (KR) runs 1.5 percent profit margins without delivery, and even them trying to deliver makes us nervous as shareholders. In our opinion, there is no way to succeed as primarily a grocery delivery company. It all looks like the definition of insanity to us.

Therefore, the stocks the market and research analysts love turned sour, while the rest of the stock market was depressed by the fallout of letting all the success in our society go to a bunch of monopolistic tech companies with a revenue-growth “hall pass!” Rarely has the spread between the growth and value indexes been this big and the price-to-earnings ratio of our portfolio hasn’t been this cheap on a forward 12-months earnings basis since 2011.

What can investors expect as a result of this situation? None of the prior manias ended well and it took more than a decade to put the humpty-dumpty-like popular stocks back together. Those investors trying to play Amazon or Netflix and similar investments are begging to reverse recorded economic history. When the market participants decide that they need to go elsewhere, they may find many bargains among companies that have been left for dead during the e-commerce mania.