After Covid-19 arrived in 2020, a lot of wealthy people fled locked-down California. Elon Musk, the world’s second-richest human, moved to Texas, griping that the Golden State had become “a little complacent, a little entitled.” Venture capitalist Keith Rabois headed to Miami, saying that “San Francisco is just so massively improperly run and managed that it’s impossible to stay here.” Other prominent tech figures decamped for Nevada, Colorado, Wyoming and elsewhere.

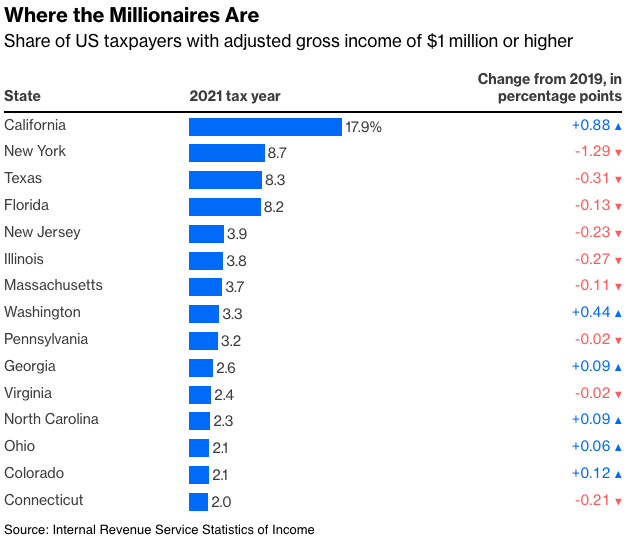

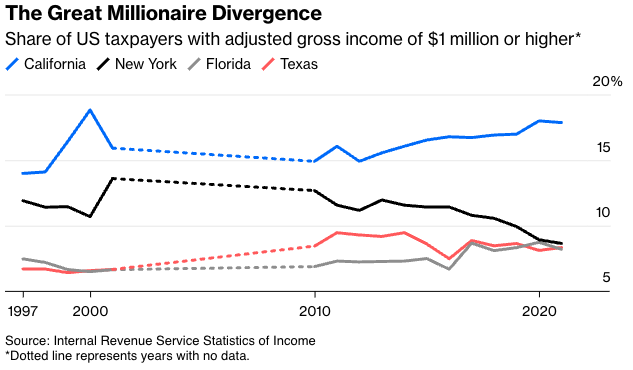

It might come as a surprise, then, that the number of California residents with incomes of $1 million or more grew by 61,900, or 66%, from 2019 to 2021, according to statistics released last week by the Internal Revenue Service. Booming asset markets and pay increases sent the number of tax millionaires up sharply in every state, and their numbers more than doubled in Montana, Idaho and Utah, but California’s percentage increase was above average. Its share of U.S. millionaires rose to 17.9% in 2021 from 17% in 2019, while those of next three most populous and millionaire-filled states—New York, Texas and Florida—fell.

It’s not that the exodus of affluent Californians was a mirage. From 2020 to 2021 (more precisely, from when people filed their 2019 taxes to when they filed their 2020 taxes), 403,041 taxpayers with an average adjusted gross income of $125,362 left California for elsewhere in the U.S., and just 241,216 with an average income of $87,072 moved in. (The IRS will release 2021-2022 migration data in June.) But rising incomes in the state minted enough new homegrown millionaires to replace all the departers and then some.

This income bump owed a lot to the spectacular growth that California-based tech companies experienced in 2020 and 2021, and the accompanying spate of initial public offerings. The subsequent tech downturn—the Nasdaq Composite Index fell nearly 60% from late 2021 to late 2022—means the state’s share of U.S. tax millionaires probably fell in the 2022 tax year. Since then, though, an artificial-intelligence boom centered in San Francisco has driven Nasdaq to records, and Musk and Rabois have moved back part time (although I imagine they’ll keep their primary residences in Texas and Florida, which don’t have a state income tax). California has a long history of weathering tech ups and downs and the departure of exasperated rich people and continuing to come out on top.

As is apparent from the above chart, it’s a different story for New York, which has ranked fourth in population since Florida passed it in 2014 and is now just barely holding on to second in the tax millionaire rankings. It was an analysis of the decline in New York’s millionaire share by E.J. McMahon of the conservative Empire Center in that inspired me to dig into this IRS data. So what’s going on with New York?

State and local taxes are surely a factor, and New York has the nation’s highest. Florida’s are the 11th lowest, by the Tax Foundation’s accounting, and the state has long been a popular retirement destination for affluent Northeasterners and Midwesterners. The sharp upward move in Florida’s millionaire share in tax year 2017 (which reflects where people lived when they filed their tax returns in 2018) may have had something to do with the $10,000 state and local tax deduction cap imposed by Congress at the end of 2017, which increased the payoff for moving there from a high-tax state. (Low-tax Texas appears to have benefited as well.)

But why then has the share of millionaires for California, which has lower taxes overall than New York but similar income tax rates for high earners, grown and grown? Why has that of Texas declined over the past decade?

The changing fortunes of key local industries clearly matter, too. In Texas, the millionaire-minting shale-oil boom that began around 2010 waned at mid-decade and then came back as a more efficient phenomenon dominated by Big Oil that doesn’t seem to be making as many Texans rich. In New York, the millionaire-heavy financial sector has ceased to be much of a growth industry, with employment in financial activities statewide and in New York City lower now than it was in 1990. Neighboring Connecticut and New Jersey have also experienced big declines in their millionaire shares since 2010. Meanwhile, the booming tech sector has delivered big gains in millionaire share since 2010 not just for California but also Washington, Colorado and North Carolina.

Millionaire movements can have a big impact on state finances. In 2022, according to the Census Bureau, individual income taxes generated 59.5% of state tax revenue in New York and 52.1% in California (the national average was 38.2%). In both states, millionaires pay around 40% of individual income taxes. Because the highest incomes tend to move up and down in tandem with asset prices, this means a lot more revenue volatility than in states (such as Texas and Florida) that depend primarily on sales taxes. It also fuels chronic worries of a millionaire exodus that could make it impossible to pay the bills.

There was such an exodus in 2020 and 2021, but booming asset markets more than canceled it out. The number of tax millionaires in New York jumped from 2019 to 2021 even as the state’s share of U.S. millionaires fell, and while according to state data the millionaire count declined in 2022 it remained 24% higher than in 2019. New York clearly has been losing ground relative to the rest of the country, though. California, despite all its doubters, has not.

Justin Fox is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering business, economics and other topics involving charts. A former editorial director of the Harvard Business Review, he is author of The Myth of the Rational Market.