The FMI Common Stock Fund is a value-focused, small-cap/mid-cap product (also known as SMID) with an impressive track record during the past 15 years. On average, it has outperformed its Russell 2000 Index benchmark by a comfortable margin. And depending on the time frame, it has remained within shouting distance of—or exceeded—the performance of the large-cap S&P 500 during that period.

So when Milwaukee-based asset manager Fiduciary Management Inc. states that the next 15 years will likely create economic conditions that could keep the good times rolling for the fund, it might scream of boosterism. But the firm posits that the massive fiscal and monetary stimulus of the past decade and a half created too much liquidity and encouraged what it calls “uneconomic activity” such as suspect mergers and acquisitions, a raft of unprofitable companies going public, and hefty increases in leverage.

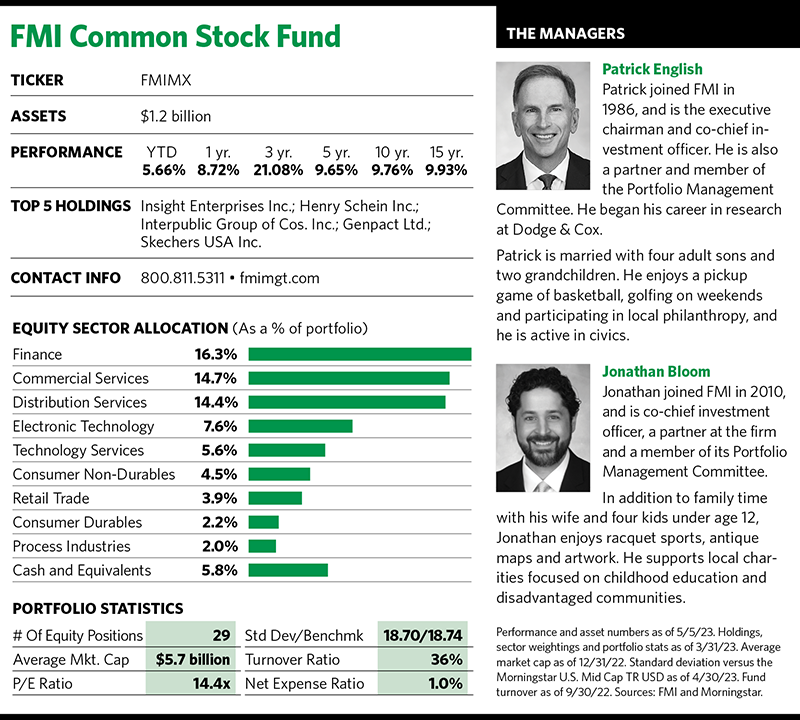

“We think the economy is poised for a much stronger, healthier run during the next 15 years than the past 15 years,” says Patrick English, FMI’s executive chairman, who co-manages the Common Stock Fund with Jonathan Bloom.

He reasons that the cost of capital was suppressed and manipulated down to a “ridiculous level” that actually suppressed growth because it resulted in companies buying each other rather than investing and growing organically. “If low interest rates are good for the economy we should’ve had the fastest growing economy in our history in the past 15 years, and it was actually the slowest,” he points out.

Bloomberg data on U.S. average real GDP growth during the past five 15-year increments (from 1948 through 2022) show that growth averaged from 3% to 3.9% during each of those periods except for the years 2008 through 2022, when the average was 1.7%. The Great Recession that began in 2008 didn’t help matters, but that was followed by a tremendous infusion of artificial liquidity that English believes fostered bad corporate habits.

“We think we’re done with the period of insanely low rates and are moving back to a normal period of interest rates, which means the cost of capital will be more normal,” he says. “Which means companies will have to invest more organically, and that should be good for economic growth.”

As a result, he and his firm believe that a return to basics should be good for the investment strategy that underpins the FMI Common Stock Fund.

40-Plus Years

FMI was founded in 1980, and as of this year’s first quarter had roughly $14 billion in assets under management for registered investment advisors, domestic and international institutions, and individual investors through separately managed accounts and the firm’s four mutual funds. The asset mix is basically split between the SMAs and mutual funds.

English says FMI is an owner-operated firm that has been independent from the get-go and it plans to stay that way. He notes that the firm’s original focus was on the small-cap to SMID space because the firm’s managers felt that’s where most of the value resided.

“As the firm grew and time went on, we felt there wasn’t much difference in how we did our research between a larger-cap company and a smaller-cap company,” English says, adding that the firm later created funds tailored to the large-cap and international spheres.

The Common Stock Fund’s 42-year track record makes it the firm’s oldest mutual fund by 20 years. FMI says the fund aims to buy good businesses with attributes such as high recurring revenue and returns on invested capital in excess to their cost of capital. FMI analysts scrutinize the economics of a business and the quality of the management team in the quest to find companies with above-average growth or improving profitability prospects. The end result is a concentrated portfolio of 30 to 45 mainly U.S. stocks and an annual turnover of 20% to 40%, which Morningstar says is well below that of most other funds in the Common Stock Fund’s mid-cap blend category.

From a style box perspective, the fund straddles the line between blend and value, but FMI proudly waves its value banner. “We’re long-term, valued-oriented investors, but good businesses don’t go on sale for no reason,” says Bloom. He explains the fund looks for companies with some type of transitory cloud or controversy hovering over them that the fund’s managers think will eventually clear up but that in the near term cause the companies’ shares to sell at discounts to their intrinsic value.

“We look to avoid value traps regarding companies we think face insurmountable secular challenges,” he says. “And we try to invest in management teams that care about their stock and think and act like shareholders.”

The FMI managers are also very focused on downside protection. “We start our process focused on what could go wrong with our investments before what could go right,” Bloom says. “And we’ve got a long history in our 40-plus years of protecting our clients on the downside in tough markets while capturing what we hope is most of the upside in rising markets and do that through a cycle.”

Morningstar analyst Chris Tate says capital preservation has helped underpin the Common Stock Fund’s long-term success. In a report, he noted the fund has held up much better than its Russell 2000 benchmark in each major downturn since English joined FMI in 1986. Last year the fund lost 5.9% while the Russell 2000 dropped 21.3%.

Win Some, Lose Some

In the same report, Tate offered that FMI is “value-focused to a fault to avoid paying for a good business above its intrinsic worth.” The result, he wrote, is that the fund has experienced periods of underperformance during rallies in smaller companies. But he acknowledged the fund’s emphasis on downside protection has shown its worth over the long term with category- and index-beating performance.

Indeed, the Common Stock Fund’s average annual returns have placed it in the top quartile in Morningstar’s mid-cap blend category during each measurable period from one year to 15 years.

English doesn’t take exception to Tate’s comment about FMI being value-focused to a fault. “When you do what we do you have to realize that sometimes you’re going to miss out on some great stocks because you think the price the market is paying for those names is too rich. We just don’t play in those types of names,” he says.

He adds that FMI prefers to stick with more reasonably priced names with solid balance sheets that offer downside protection. “We’d rather get into a company with a solid but more sustainable growth rate and where we’re not paying for high expectations.”

FMI says its approach appeals to its investor base, which includes clients of independent RIAs who have already made their money and want to keep it. These are investors seeking equity returns but with an eye toward downside protection.

The Next 15 Years

FMI highlights the contrarian nature of the Common Stock Fund, which Bloom says results from its value orientation, where the managers lean into the wind and venture into out-of-favor stocks. “From our perspective, to beat the market you must do something different from the market. We go into situations where businesses are out of favor,” he explains.

One example is Skechers, one of the world’s largest footwear companies and one of the fund’s recent largest holdings. Bloom likes the company’s high return on invested capital, its net cash position and its high level of insider ownership, among other attributes. He notes the fund started building a position in the company’s stock after the price dropped when elevated supply-chain costs weighed on its profit margins.

“Skechers is a business that in our view should be trading at a much higher multiple than it has been in recent years,” Bloom says, though the company has rebounded during the past six months and recently hit a 52-week high.

Bloom says the fund has a flat management structure where the staff of seven analysts that he and English work with have the function of portfolio managers. “Pat and I, as co-CIOs, are more like traffic cops who work with each of our analysts to vet the individual ideas and serve more in the role of a traditional portfolio manager as you think of it at other organizations,” Bloom says. “We’ll spend anywhere from several weeks to several months with our analysts on a particular idea.”

Bloom was named FMI’s co-chief investment officer at year-end 2022 as part of the firm’s transition to new leadership. English says he’ll give up day-to-day active involvement at the end of 2025. “I’ll remain chairman. I’ve never sold a share of our stock, so I have a high degree of interest in making sure everything continues to work beautifully,” he says.

And that includes positioning the Common Stock Fund to capitalize on what he and Bloom believe will be a constructive economic environment during the next 15 years.