It’s become all too common to attribute the surge in emerging-market assets this year to the cheap cash sloshing around the world courtesy of central banks. But that’s only half the story.

Sure, faced with negative debt yields in many developed countries, investors have cast their nets far and wide to bolster returns, often pouring money into the bonds, stocks or currencies of nations mired in recession.

But some of the most troubled emerging economies and companies in recent years are actually giving money managers reasons to pile in. China is now on pace to hit its growth target, while Brazil and Russia are poised to emerge from their slumps. Developing nations have also boosted their foreign reserves by $144 billion to $9.9 trillion after they sank to a three-year low in March. The more than 800 companies in MSCI’s Emerging Markets Index posted average growth in earnings-per-share of 47 percent in the latest quarter, while profit for members of the Standard & Poor’s 500 Index fell.

“There are signs that things are looking better, or at least less bad,” said Kieran Curtis, an investment director at Standard Life Investments Ltd. in London, which has $350 billion of assets under management. “The stabilization in Brazil and Russia is having a big impact on the aggregated growth rate of emerging markets.”

While yields on developing-nation bonds have plunged 1.25 percentage points since January to 4.23 percent as investors scooped up the debt, they’re still well above much of what you get in places such as the U.S., the Eurozone and Japan. There are about $8.9 trillion worth of bonds with negative yields globally.

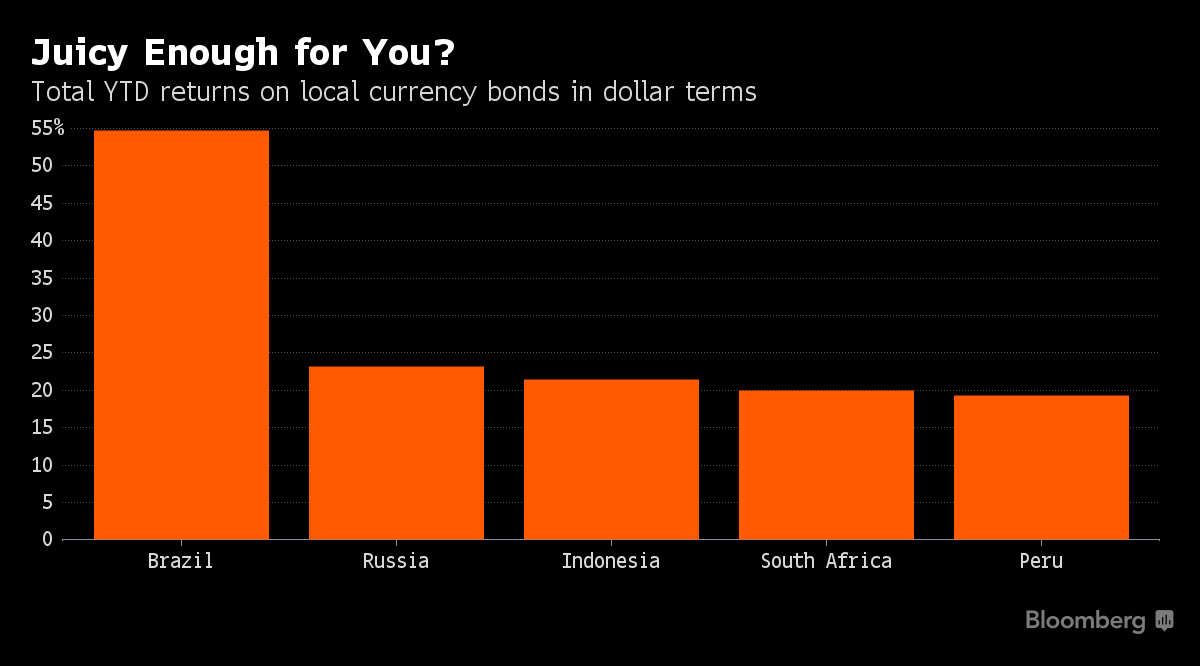

Investors in hard-currency emerging-market debt have reaped average returns of 12.7 percent this year, led by gains in Venezuela and Zambia. Meanwhile, an index of 20 developing-nation currencies has jumped 5.2 percent in 2016, on pace for the biggest surge in seven years. MSCI’s emerging-market stock gauge is up 13 percent this year, almost four times as much as the broader MSCI World Index of developed-nation stocks. An index of emerging-market currencies has gained 4.3 percent this year, on course to end three years of declines.

“It’s safe to assume that yields in emerging markets will continue to come down,” said Jim Barrineau, a New York-based emerging-market money manager at Schroder Investment Management Ltd., which has about $450 billion in assets worldwide. “Fundamentals are improving. Fundamentals always follow liquidity. First we get liquidity flow, then you get the central banks lowering rates, then you get the currencies appreciating, then you get better growth.”

Companies and households in developing nations are starting to reduce borrowing as a percentage of their economies. Excluding China, the credit-to-gross-domestic-product ratio has dropped to 127 percent, from 128 percent at the end of last year, marking the first decline since the global financial crisis, according to data compiled by Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

Emerging-market companies in particular are slashing debt levels that had become increasingly worrisome amid a tumble in currencies in recent years.

Brazilian firms led by state-owned oil company Petroleo Brasileiro SA cut their average net debt to earnings before items to 2.2 times last quarter from 2.6 times a year earlier. Petrobras, as the crude producer is known, shaved $8.9 billion off its balance sheet.