Summary

• Addressing climate, publicly and privately.

• The Green New Deal

• Petro-states contemplate life after carbon

I was born too early to benefit much from Sesame Street, but I still loved The Muppets. Kermit the Frog was my favorite character; alternatively in full control and overwhelmed, Kermit struggled to make sense of the nonsensical. To this day, there are times that I feel confronted with the same challenge.

Kermit produced numerous pearls of wisdom, such as:

“Beware of advice from experts, pigs, and members of Parliament.”

“It’s nice to be important. But it’s important to be nice.”

“May success and a smile always be yours…even when you’re knee deep in the sticky muck of life.”

Among Kermit’s more famous quotes was “It’s not easy being green.” Kermit’s lament came to mind several times recently, during economic conferences that touched on the impact of climate change. As the earth warms and the consequences of warming become more apparent, the issue has reached heightened prominence. Debate is now centered on whether markets or mandates are the best tool to bend the carbon curve.

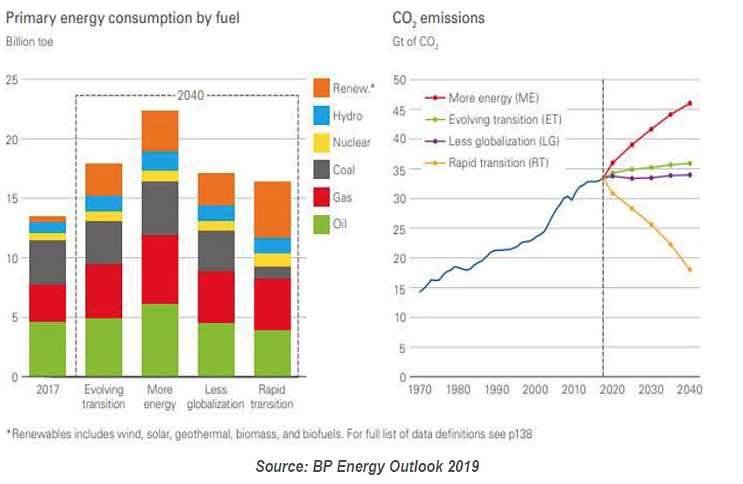

We detailed the situation in last fall’s essay, “Changing Climate.” The globe has set a long string of record temperatures, and the frequency of severe storms has increased. Recognition that human production of carbon dioxide (CO2) has played a role in the process has become widespread, as has the resolve that something needs to be done.

Arresting the problem will require significant structural and behavioral changes. Accelerating the shift of power generation to environmentally friendly fuels would require scrapping existing facilities and making substantial investments in new ones. In a similar vein, shifting cars from internal combustion engines to batteries will not be done cheaply or easily. These are just two of the many frictions that make the transition to a greener future expensive and difficult. And the faster the transition, the more significant these frictions become.

Furthermore, reducing carbon footprints will almost certainly be accompanied by substantial economic dislocations. We’ve already seen examples of this in coal-producing regions around the world; we may one day also see them in areas that produce other fossil fuels. If one country moves more aggressively than others, it risks placing its industries at a competitive disadvantage. Transition plans will have to be carefully crafted.

Addressing climate change has been difficult for politicians. They are often focused on the electoral cycle, which is much shorter than the time frame over which the consequences of a warming planet will be felt. But we are all at fault: behavioral scientists have established that human beings have inherent trouble estimating the long-term consequences of our behavior. Dealing with long-term issues like climate change is easily deferred.

It does appear that global policymakers are beginning to take the topic up in earnest, though. Proposals to slow global warming fall into two categories: regulatory and market-based. In the former are concepts like the Green New Deal, which has been advanced by some of the newcomers to the U.S. Congress. (And which is covered in a separate segment in this issue.) Its targets present a high bar for industry and households to clear.

On the market side are approaches like carbon taxes or cap-and-trade systems. Forty countries are already using one of these two devices, which attempt to provide incentives for producers and consumers to reduce emissions. Monies generated from carbon taxes are often used to promote investment in clean technology; cap-and-trade markets have the advantage of setting a desired level of emissions and letting market participants work towards equilibrium.

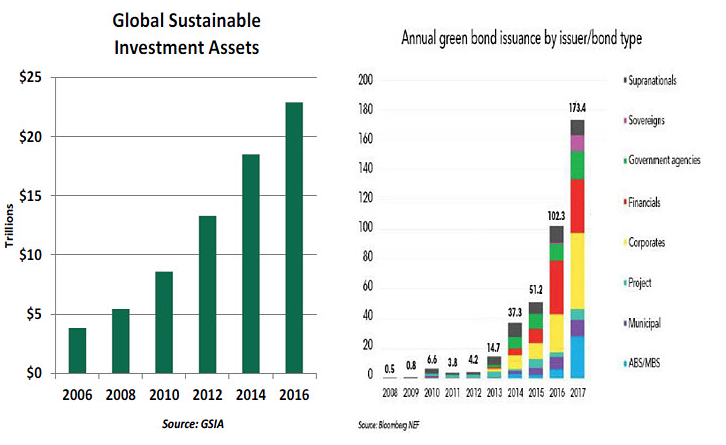

The private sector is also pressing a greener agenda. A broadening number of firms are issuing regular reports on corporate social responsibility, which highlight their efforts to operate sustainably. (Northern Trust’s most recent report can be found here.)